Chapter 7Implicit differentiation, what's going on here?

"Do not ask whether a statement is true until you know what it means."

- Errett Bishop

Let me share with you something I found particularly weird when I was a student first learning calculus.

Implicit Curves

Let's say you have a circle with radius centered at the origin of the -coordinate plane. This shape is defined using the equation . That is, all points on this circle are a distance from the origin, as encapsulated by the pythagorean theorem where the sum of the squares of the legs of this triangle equals the square of the hypotenuse, .

And suppose you want to find the slope of a tangent line to this circle, maybe at the point .

Now, if you're savvy with geometry, you might already know that this tangent line is perpendicular to the radius line touching that point. But let's say you don't already know that, or that you want a technique that generalizes to curves other than circles.

As with other problems about the slopes of tangent lines to curves, they key thought here is to zoom in close enough that the curve basically looks just like its own tangent line, then ask about a tiny step along that curve.

The -component of that little step along the curve is what you might call , and the -component is a little , so the slope that we want is the rise over run .

But unlike other tangent-slope problems in calculus, this curve is not the graph of a function. We cannot take a simple derivative, like we have in the past, by asking about the size of a tiny nudge to the output of a function caused by some tiny nudge to the input. In the equation is not an input and is not an output, they're both just interdependent values related by some equation.

This is called an "implicit curve"; it's just the set of all points that satisfy some property written in terms of the two variables and .

The procedure for how you actually find for curves like this is the thing I found very weird as a calculus student. You take the derivative of both sides of this equation like this:

- For the derivative of you write .

- Similarly, becomes .

- The derivative of the constant on the right is just .

You can see why this feels strange, right? What does it mean to take a derivative of an expression with multiple variables? And why are we tacking on the little and in this way? Unlike with functions, there isn't clear flow from input to output. But if you just blindly move forward with what you get here, you can rearrange this equation to find an expression for , which in this case comes out to .

So at a point with coordinates , that slope would be , evidently. This strange process is called "implicit differentiation". Don't worry, I have an explanation for how you can interpret taking a derivative of an expression with two variables like this. But first, I want to set aside this particular problem, and show how this is related to a different type of calculus problem, something called a related rates problem.

Related Rates

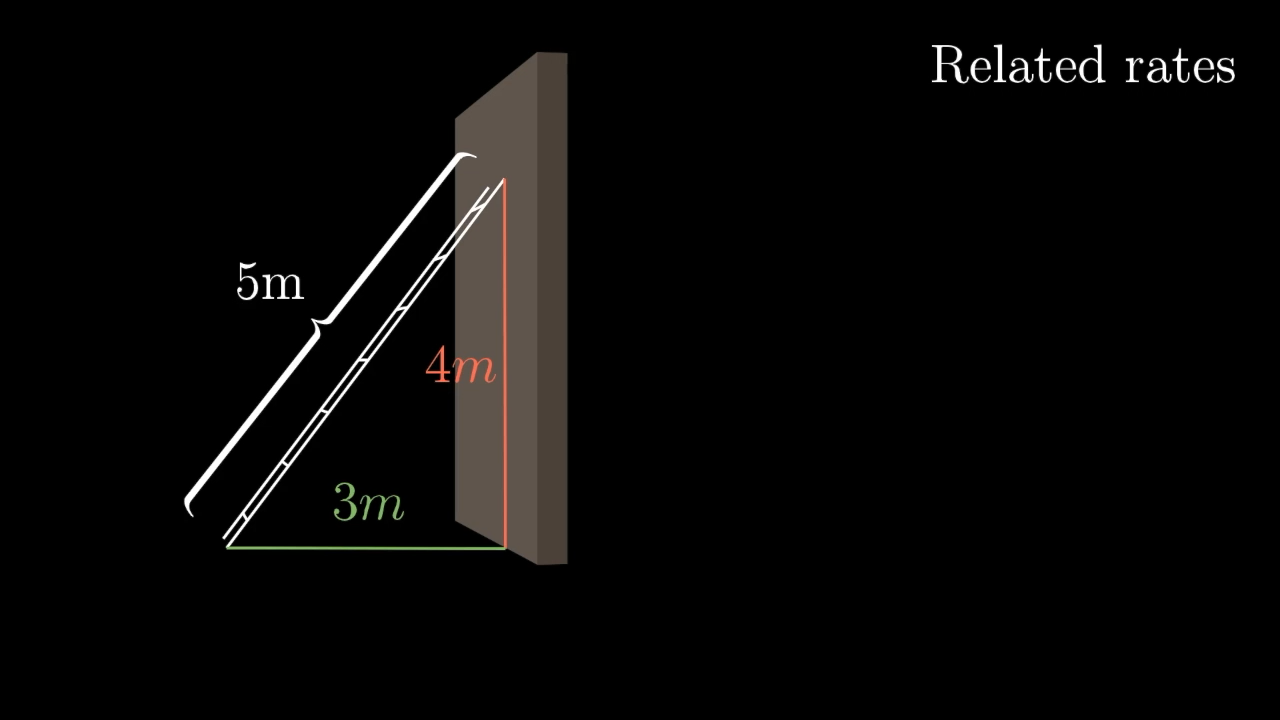

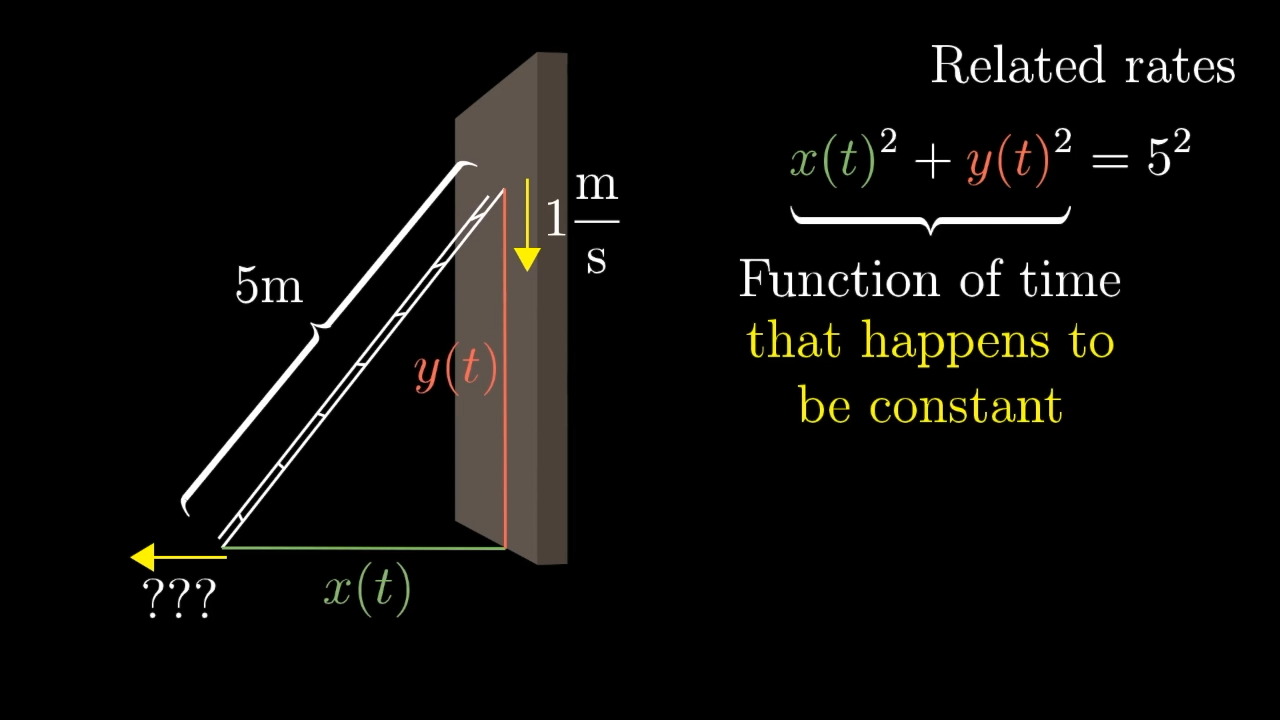

Imagine a meter long ladder held up against a wall, where the top of the ladder starts off meters above the ground, which—by the pythagorean theorem—means the bottom is meters away from the wall.

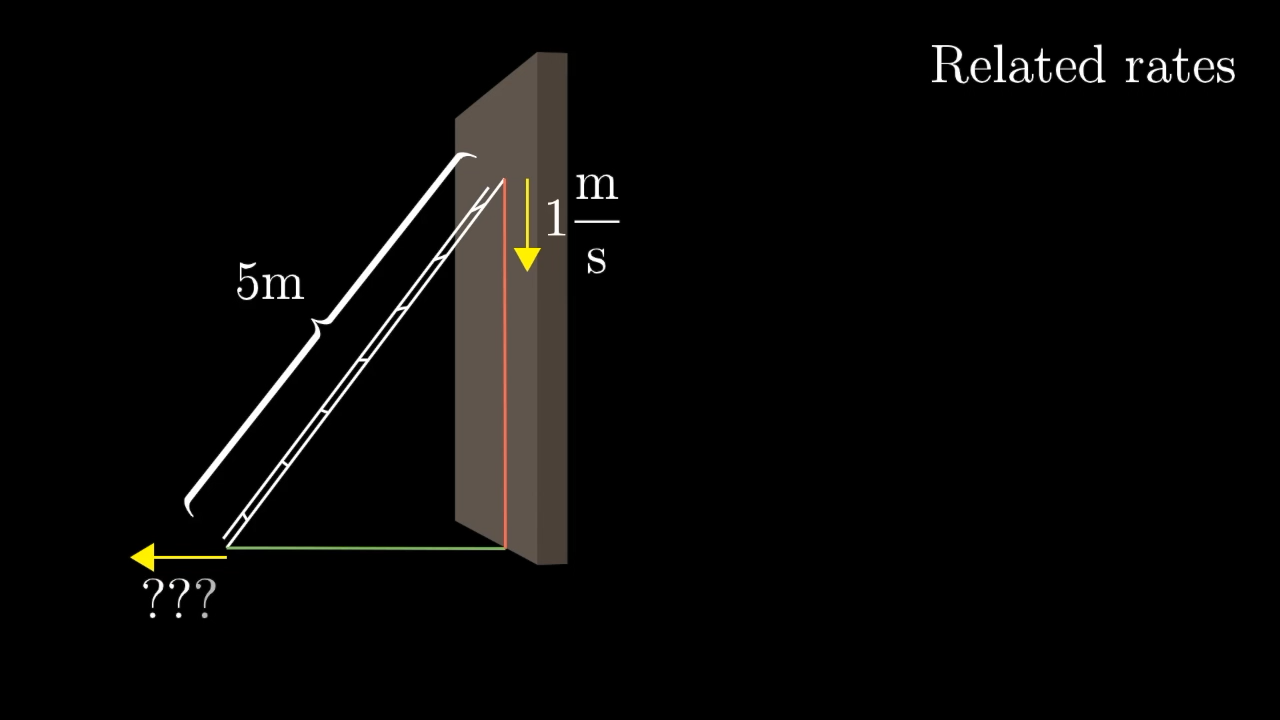

And say it's slipping down the wall in such a way that the top of the ladder is dropping at meter per second. In that initial moment, what is the rate at which the bottom of the ladder is moving away from the wall?

It's interesting, right? That distance from the bottom of the ladder to the wall is determined by the distance between the top of the ladder and the floor, so we should have enough information to figure out how the rates of change for each value depend on each other, but it might not be entirely clear how exactly you relate those two.

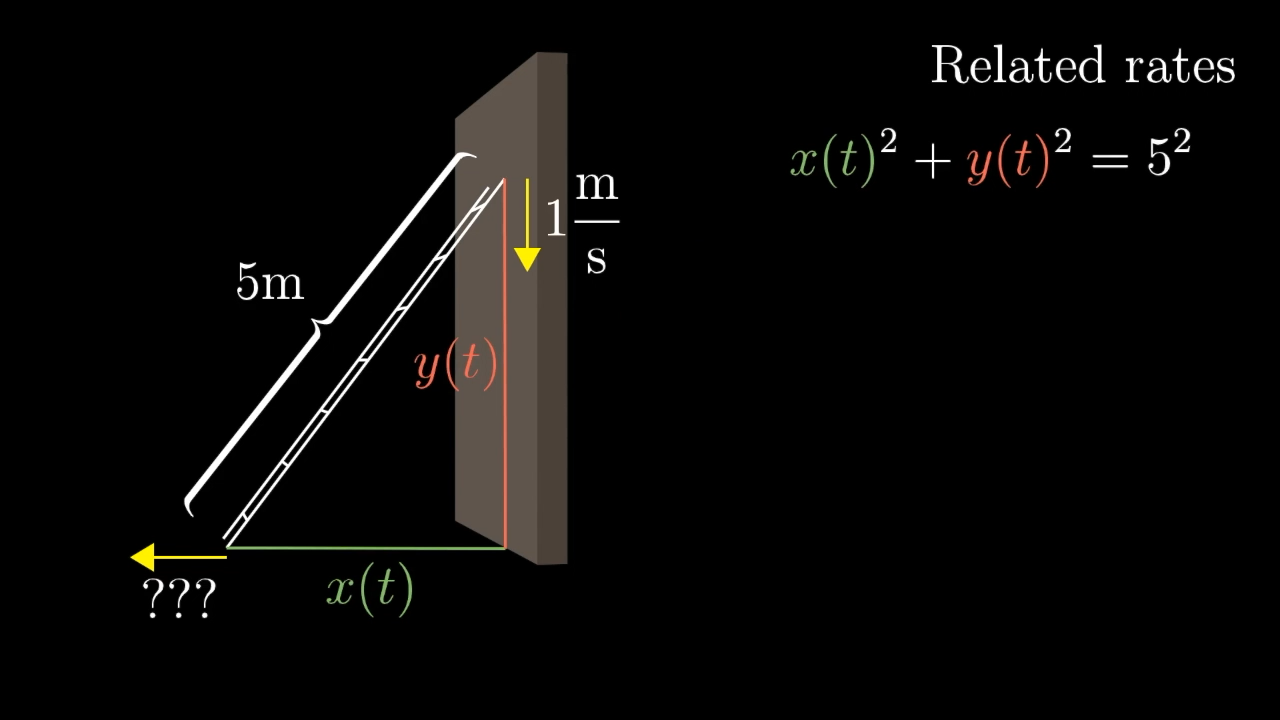

First thing's first, it's always nice to give names to the quantities we care about. So label the distance from the top of the ladder to the ground , written as a function of time because it's changing. Likewise, label the distance between the bottom of the ladder and the wall . They key equation that relates these terms is the pythagorean theorem: . What makes this equation powerful is that it's true at all points in time.

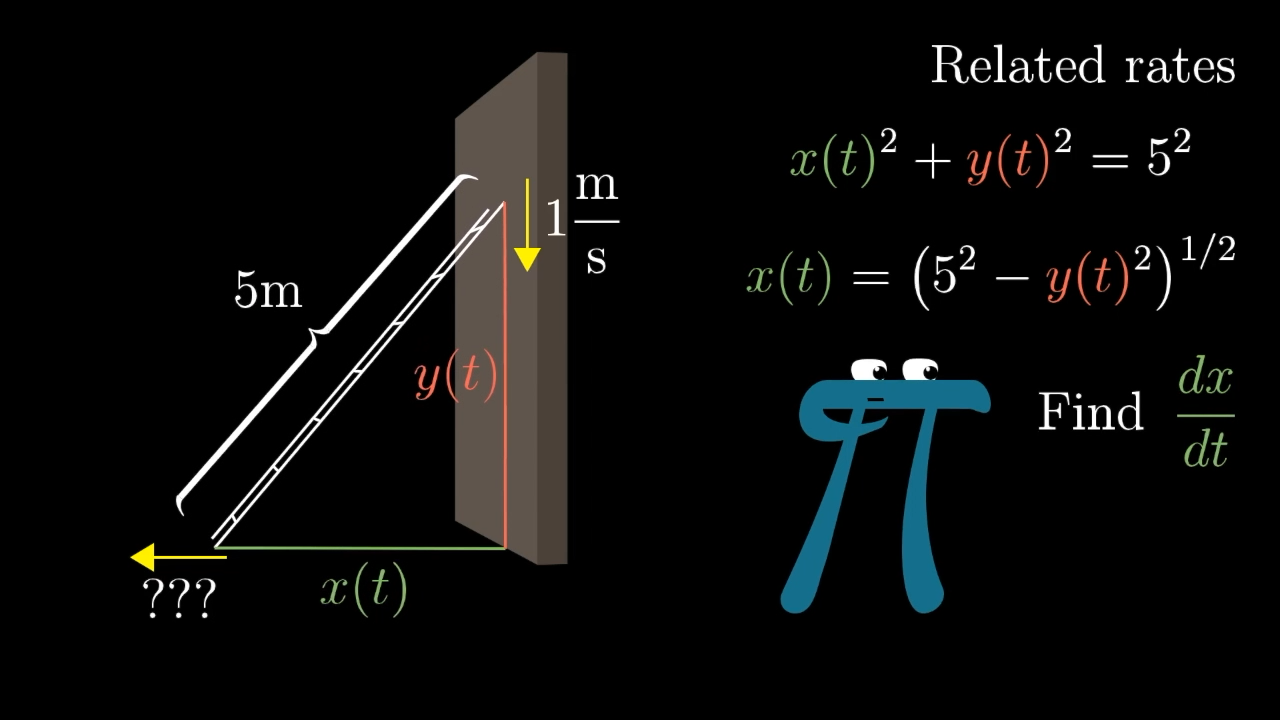

One way to solve this would be to isolate , figure out what what must be based this meter/second drop rate, then take a derivative of the resulting function; , the rate at which is changing with respect to time.

And that's fine; if you're willing to apply the chain rule a few times, this method will definitely work for you. But I want to show a different way to think about the same problem.

This left-hand side of the equation is a function of time, right? Which just so happens to equal a constant, meaning this value evidently doesn't change while time passes.

However, this expression is dependent on time which we can manipulate like any other function with as an input. In particular, we can take a derivative of the left hand side, which is a way of saying "If I let a little bit of time, , pass, which causes to slightly decrease, and to slightly increase, how much does this expression change?"

On the one hand, we know that derivative should be , since this expression is a constant, and constants don't care about your tiny nudge to time; they remain unchanged. But on the other hand, what do you get when you compute the derivative of this as a function of time?

The derivative of is times the derivative of . That's the chain rule in action. represents the size of a change to caused by a change to , and then we're dividing out by . Likewise, the rate at which is changing is times the derivative of .

Now, evidently, this whole expression must be zero, and that's an equivalent of saying must not change while the ladder moves. And at the very start, , the height is meters, the distance is meters, and since the top of the ladder is dropping at a rate of meter per second, that derivative is meters/second.

Now this gives us enough information to isolate the derivative , which, when you work it out, it comes out to be meters per second.

Implicit Differentiation

Now compare this to the problem of finding the slope of the tangent line to the circle. In both cases, we had the equation , and in both cases we ended up taking the derivative of each side of this expression. But for the ladder problem, these expressions were functions of time, so taking the derivative has a clear meaning: it's the rate at which this expression changes as time change.

What makes the circle situation strange is that rather than saying a small amount of time has passed, which causes and to change, the derivative has the tiny nudges and both just floating free, not tied to some other common variable like time.

Let me show you how you can think about this: Give this expression a name, maybe . is essentially a function of two variables; it takes every point on the plane and associates it with a number.

For points on this circle, that number happens to be .

If you step off that circle away from the center, that value would be bigger. For other points closer to the origin, that value is smaller.

What it means to take a derivative of this expression, a derivative of , is to consider a tiny change to both these variables, some tiny change to , and some tiny change to – and not necessarily one that keeps you on this circle, by the way, it's just some tiny step in any direction on the -plane.

From there you ask how much the value of changes. That difference in the value of , from the original point to the nudged point, is what we would call "" or "the change to the function ".

As we saw in previous lessons, these and expressions raised to the second power are neglible as the nudges approaches zero.

For example, say we're starting at a point , and let's just say that step is , and that is . Then the decrease to , the amount that changes over that step, will be around .

That's what this derivative expression means. It tells you how much the value changes, as determined by the point where you started, and the tiny step that you take.

As with all things derivative, this is only an approximation, but it's one that gets more and more true for smaller and smaller choices of and .

The key point is that when you restrict yourself to steps along this circle, you're essentially saying you want to ensure that this value doesn't change; it starts at a value of , and you want to keep it at a value of ; that is, should be . So setting this expression equal to is the condition under which a tiny step stays on the circle.

Again, this is only an approximation. Speaking more precisely, that condition keeps you on a tangent line of the circle, not the circle itself, but for tiny enough steps those are essentially the same thing.

Another example

Of course, there's nothing special about the expression here. You could have some other expression involving 's and 's, representing some other curve, and taking the derivative of both sides like this would give you a way to relate to for tiny steps along that curve.

It's always nice to think through more examples, so consider the expression , which corresponds to many U-shaped curves on the plane. Those curves represent all the points of the plane where the value of equals the value of .

Now imagine taking some tiny step with components , and not necessarily one that keeps you on the curve.

Taking the derivative of each side of the equation will tell us how much the value of that side changes during this step. On the left side, the product rule tells us that this should be "left d-right plus right d-left": times the change to , which is , plus times the change to , which is . The right side is simply , so the size of a change to the value is exactly , right?

Setting these two sides equal to each other is a way of saying "whatever your tiny step with coordinates is, if it's going to keep us on this curve, the values of both the left-hand side and the right-hand side must change by the same amount." That's the only way this top equation can remain true.

From there, depending on what problem you're solving, you could manipulate further with algebra, where perhaps the most common goal is to find divided by .

Finding derivative of ln(x)

As one more example, let me show how you can use this technique to help find new derivative formulas. I've mentioned in a previous lesson that the derivative of is itself, but what about the derivative of its inverse function the natural log of ?

The graph of can be thought of as an implicit curve; all the points on the -plane where , it just happens to be the case that the 's and 's of this equation aren't as intermingled as they were in other examples. The slope of this graph, , should be the derivative of , right?

Well, to find that, first rearrange this equation to be . This is exactly what the natural log of means; it's saying " to the what equals ?"

Graphically this should make sense too, since you can draw a diagonal line and reflect the functions to see that they are inverses of eachother.

Since we know the derivative of , we can take the derivative of both sides of this equation , effectively asking how a tiny step with components changes the value of each side.

To ensure the step stays on the curve, the change to the left side of the equation, which is , must equal the change to the right side, which is .

Rearranging, this means , the slope of our graph, equals .

And when we're on this curve, is by definition the same as , so evidently the slope is .

An expression for the slope of the graph of a function in terms of like this is the derivative of that function, so the derivative of is .

Exercises

What is the slope of the tangent line at the point for the implicit curve defined by the equation ? Compare this with the derivative at the point for the function .

Next Lesson

By the way, all of this is a little peek into multivariable calculus, where you consider functions with multiple inputs, and how they change as you tweak those inputs. The key, as always, is to have a clear image in your head of what tiny nudges are at play, and how exactly they depend on each other.

Next up, I'll talk about about what exactly a limit is, and how it's used to formalize the idea of a derivative.

Thanks

Special thanks to those below for supporting the original video behind this post, and to current patrons for funding ongoing projects. If you find these lessons valuable, consider joining.