Darts in Higher Dimensions [Numberphile]

The Game

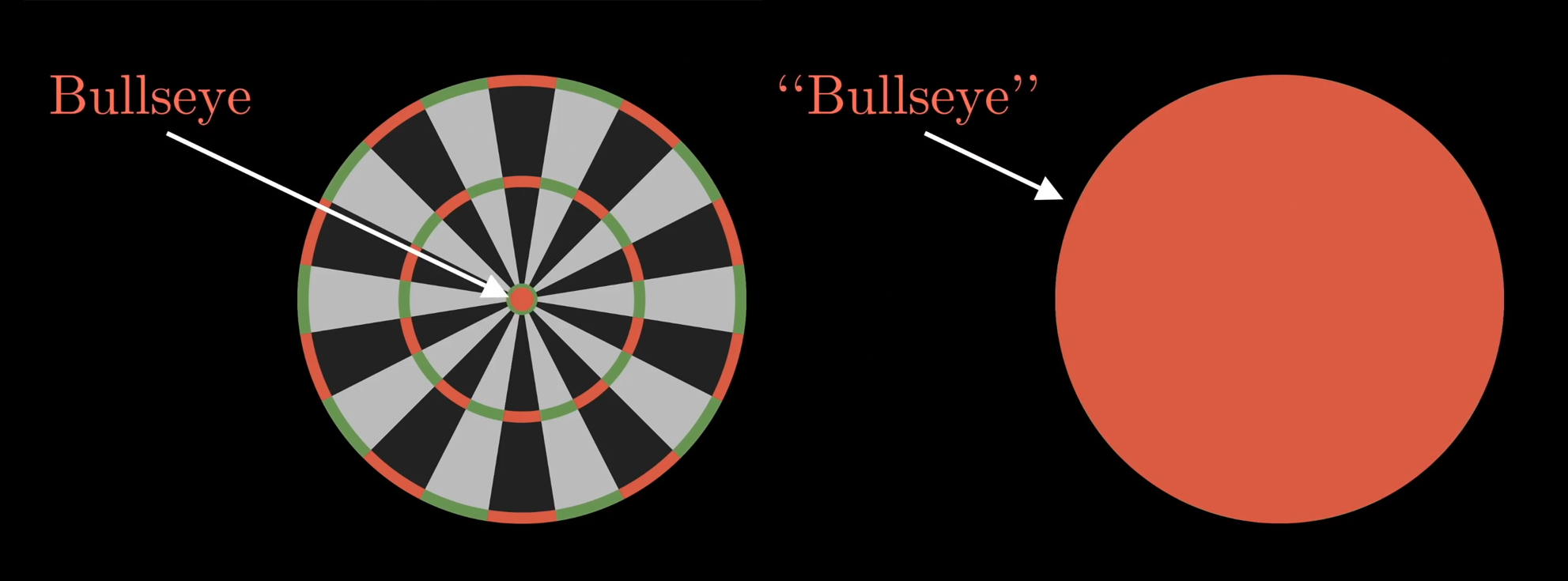

There is a lovely puzzle hidden in the midst of darts, higher dimensional geometry, statistics, and some of the most famous numbers in math. We're going to play a game of darts where we lose the game when the dart misses the bullseye. But this bullseye is too small, so to begin let's make it the entire size of the dartboard.

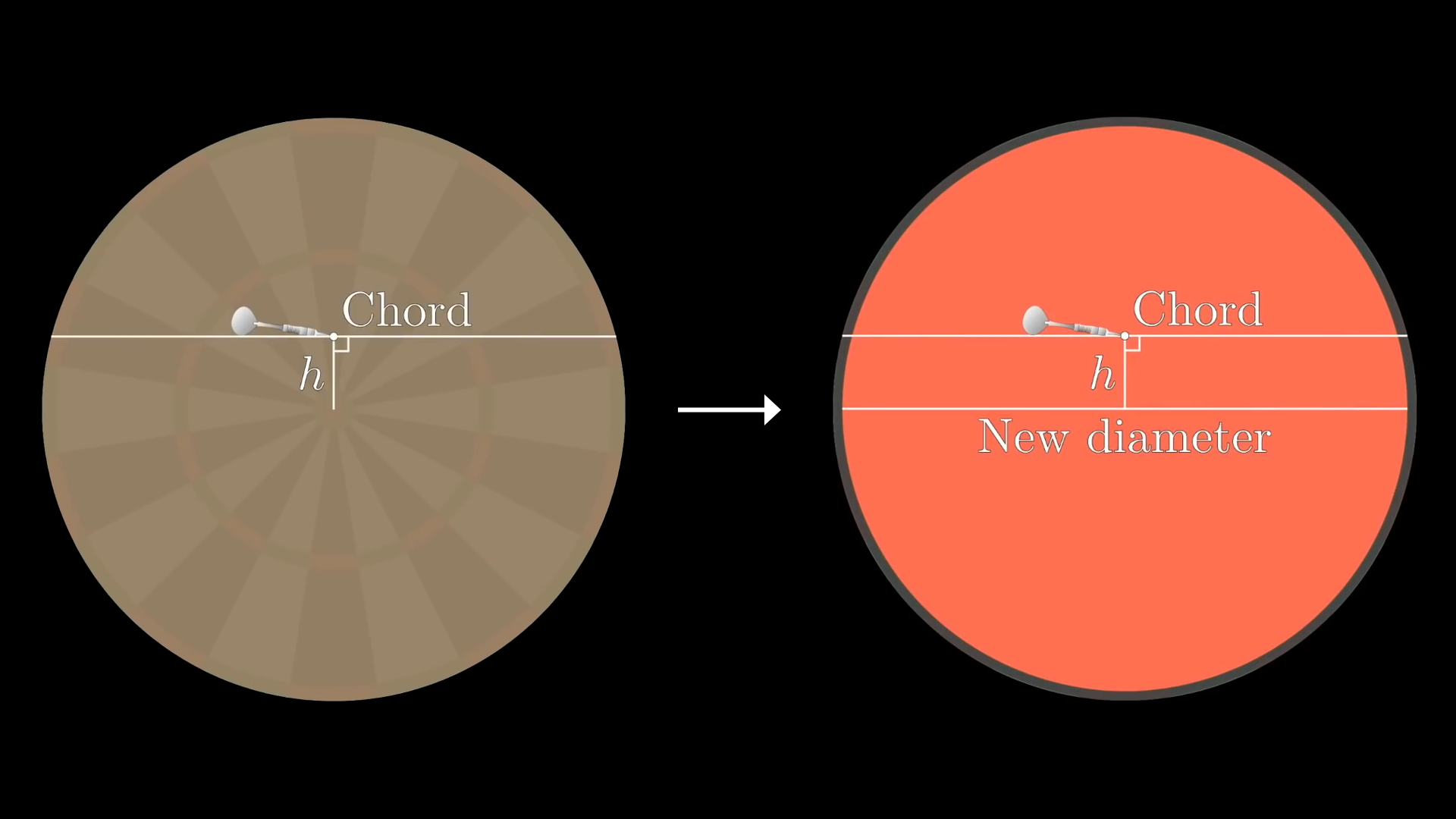

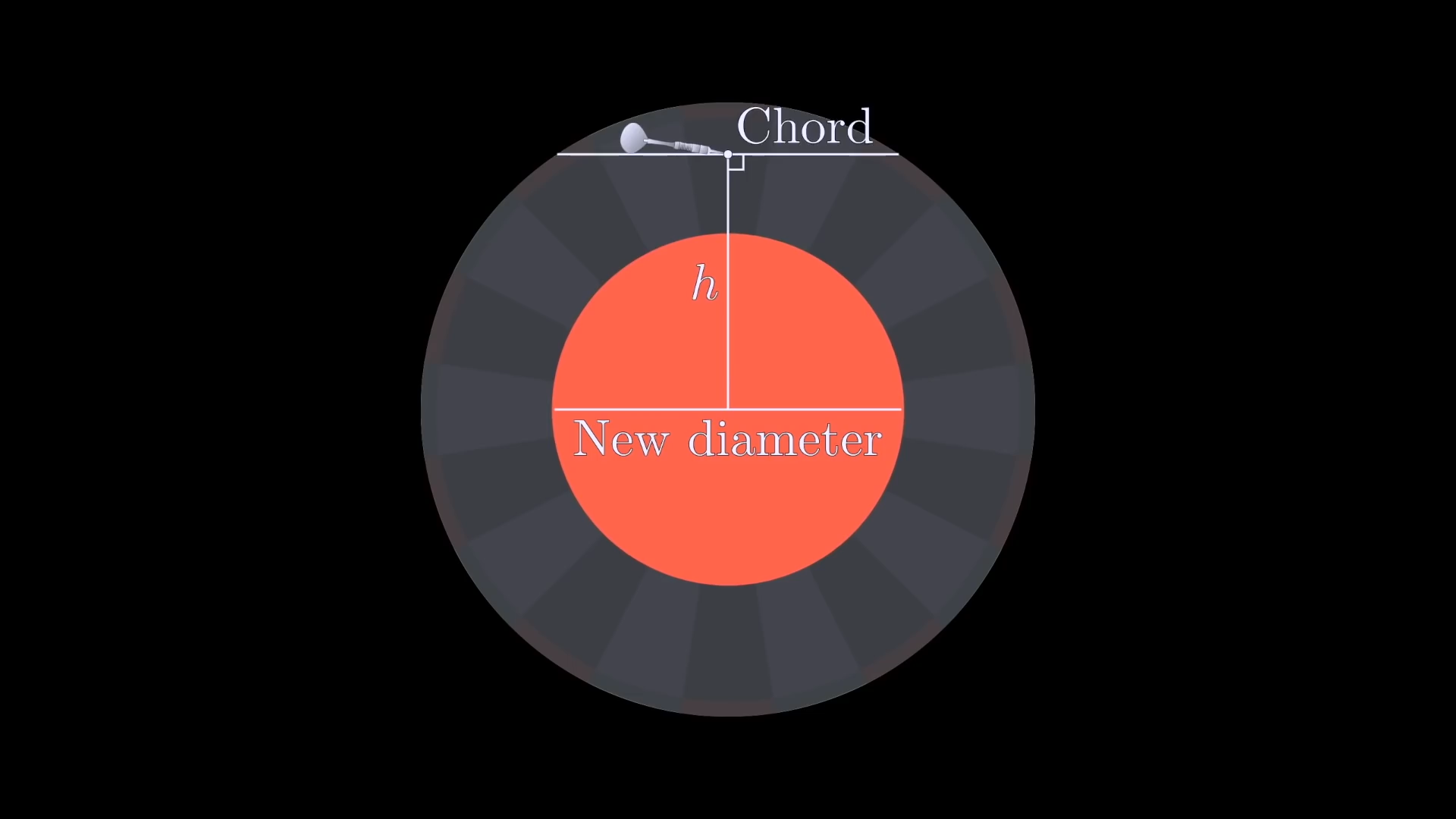

Each time we hit the bullseye, it will shrink depending on where the dart lands. This makes the rounds get harder and harder as we continue. A line will be drawn from the center of the dartboard to the landing point, we'll call this line . Then we'll draw the chord perpendicular to , whose length will define the diameter of the new bullseye.

Where does the dart have to land in order for the circle to remain unchanged?

Exactly in the center of the circle. Then the line will have a distance of and the chord's length will be the current diameter, so the circle does not shrink.

This game rewards good shots because the length of the chord will be close to the old diameter when the dart lands close to the center. When the dart lands near the edge, the new diameter will be dramatically smaller.

When a dart is thrown and it doesn't land in the bullseye, the game is over. The score is the number of darts thrown, so even if the first dart misses, the minimum score is still . Try playing the game for yourself by clicking below.

The Puzzle

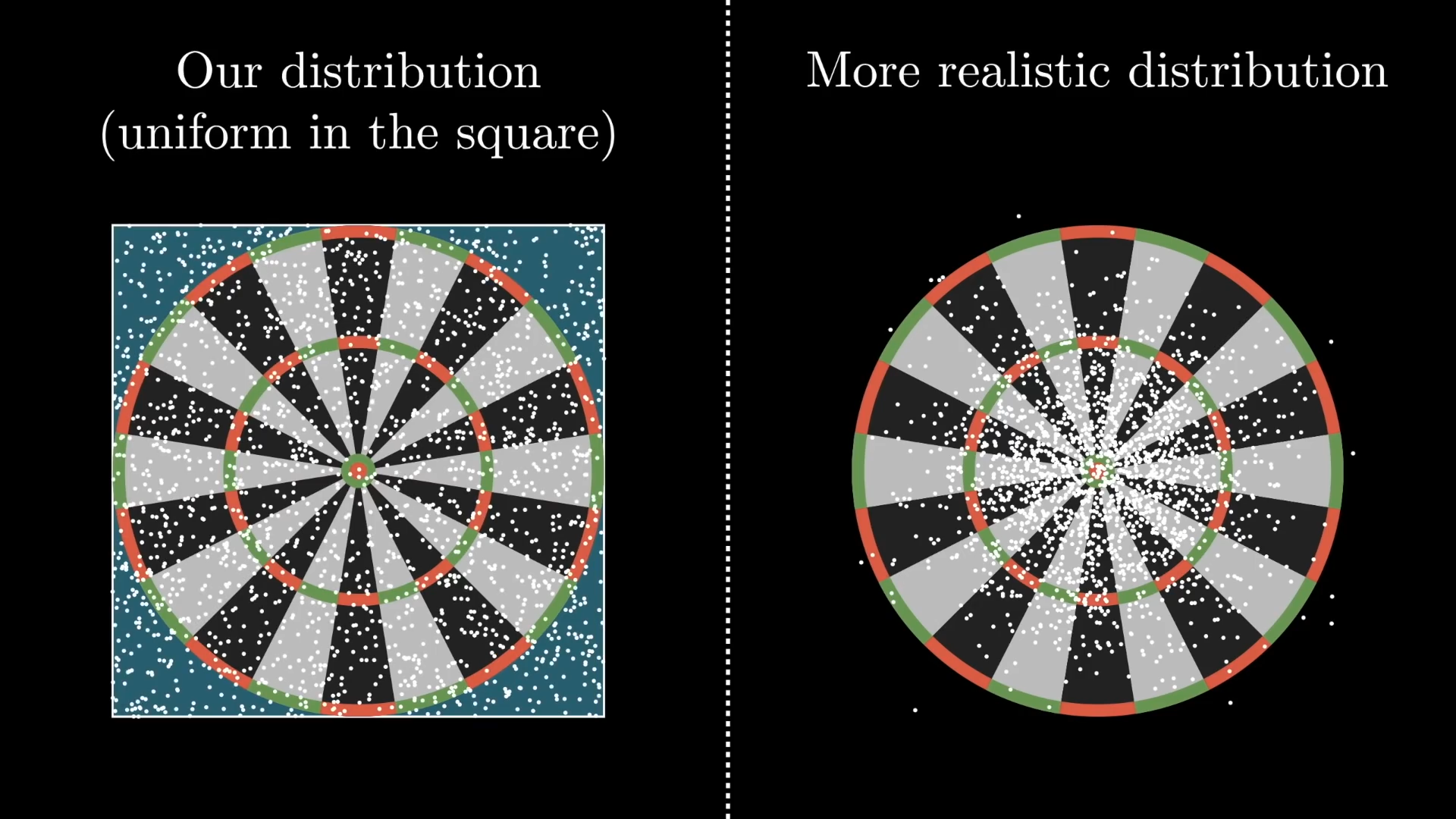

Instead of having a human playing this game, we'll create a robot who throws the darts randomly. Imagine a square that surrounds the dartboard, this robot's throws will be uniformly distributed on the square. This is not exactly a realistic distribution, which would be rotationally symmetric.

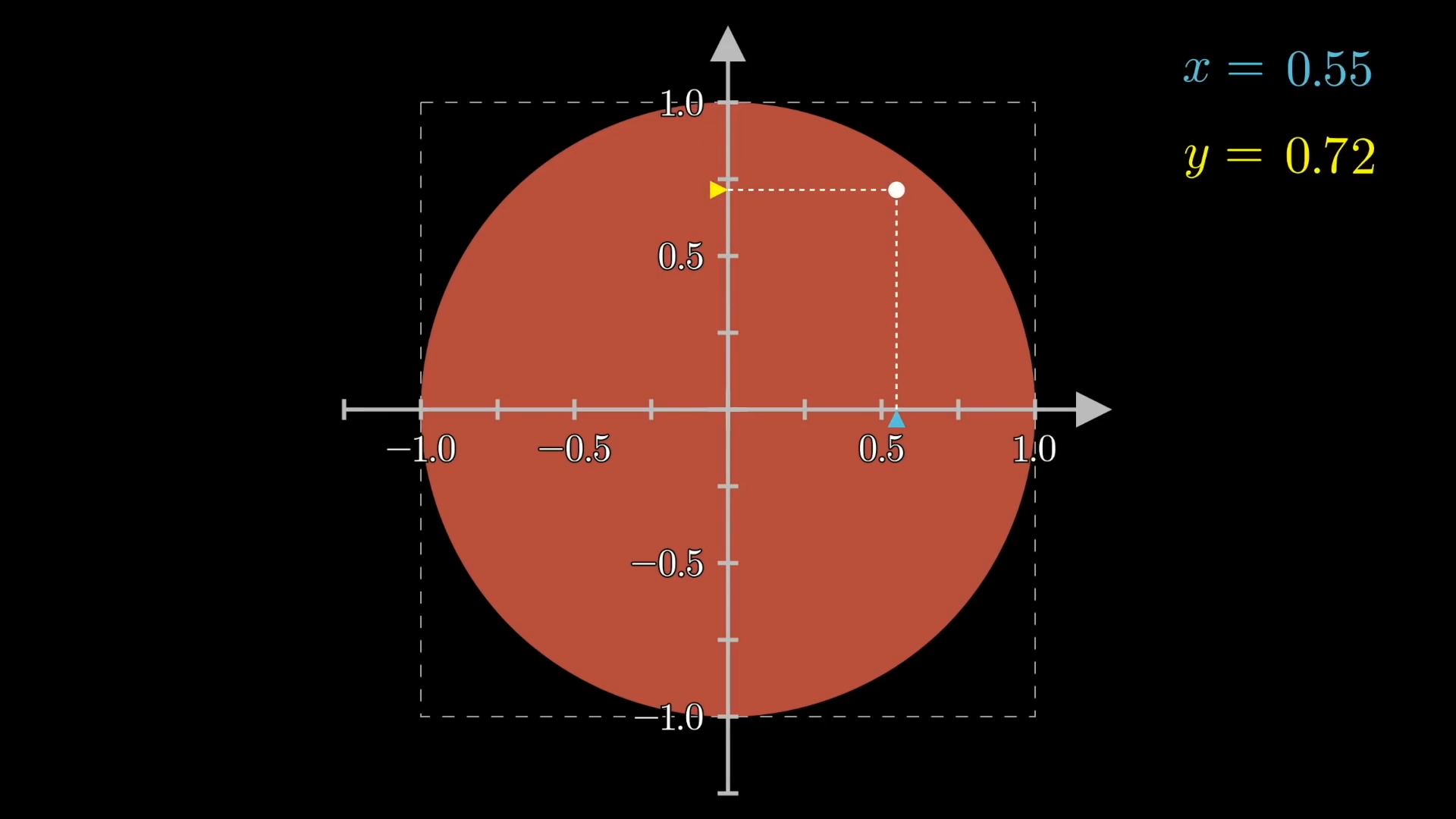

To make things simpler the dartboard is the unit circle, so each side of the square has a length of . The and coordinates of the dart's landing are chosen uniformly:

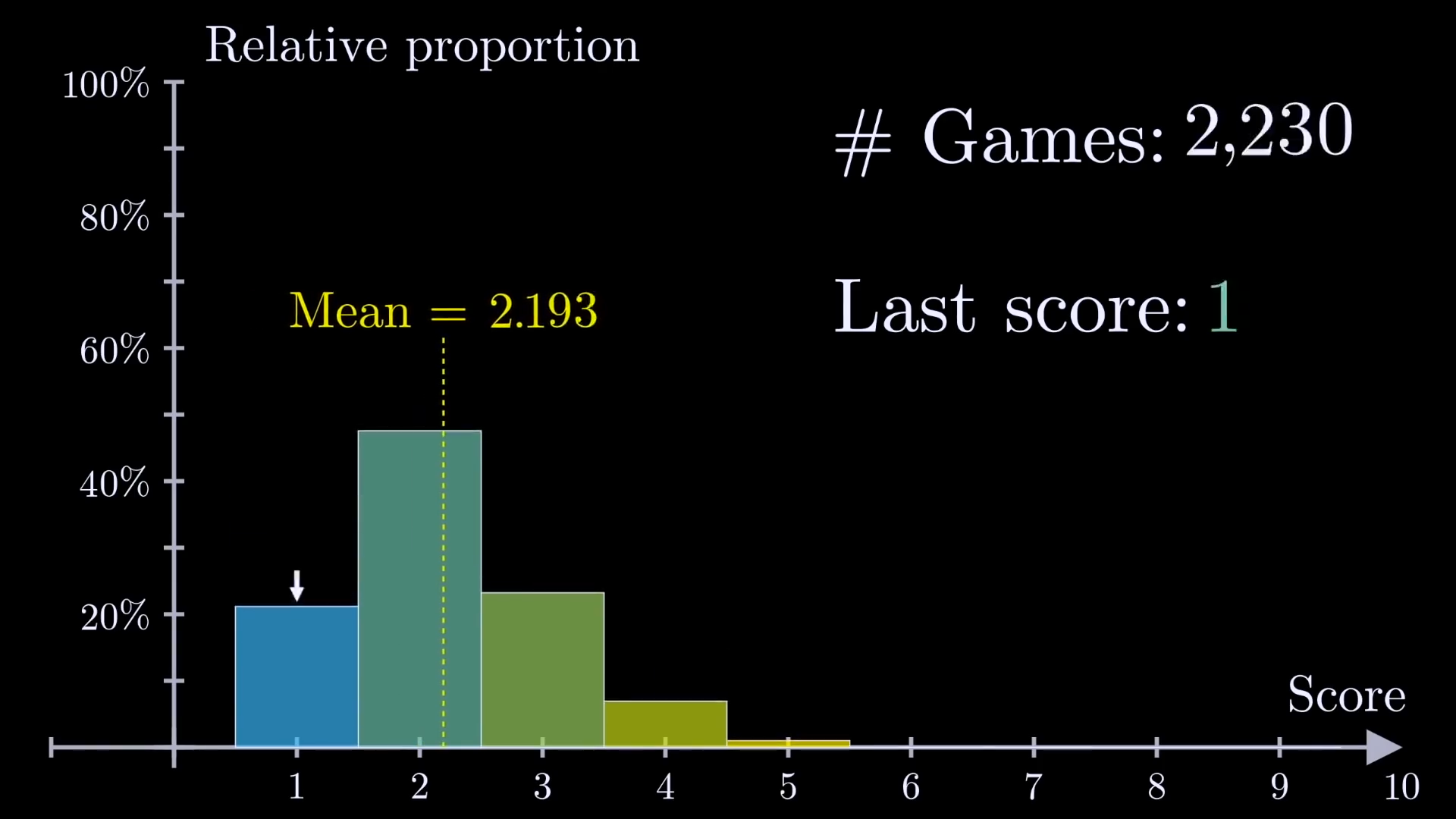

The square does not shrink with the bullseye, it always stays with the dartboard. The question to be answered is what is the expected score for this robot? As the robot plays more and more games, what is the average score?

We can calculate the expected score by adding together all of the scores multiplied by the probability that the game ends on that score.

We'll need to find what the probabilities are for each score. In theory, it is possible to have a perfect game. An expert player could hit the origin with every dart, never shrinking the bullseye. But the probability of such a game occurring is zero. A paradoxical fact about statistics is that there exist events that are possible, but their probability is zero.

Breaking It Down

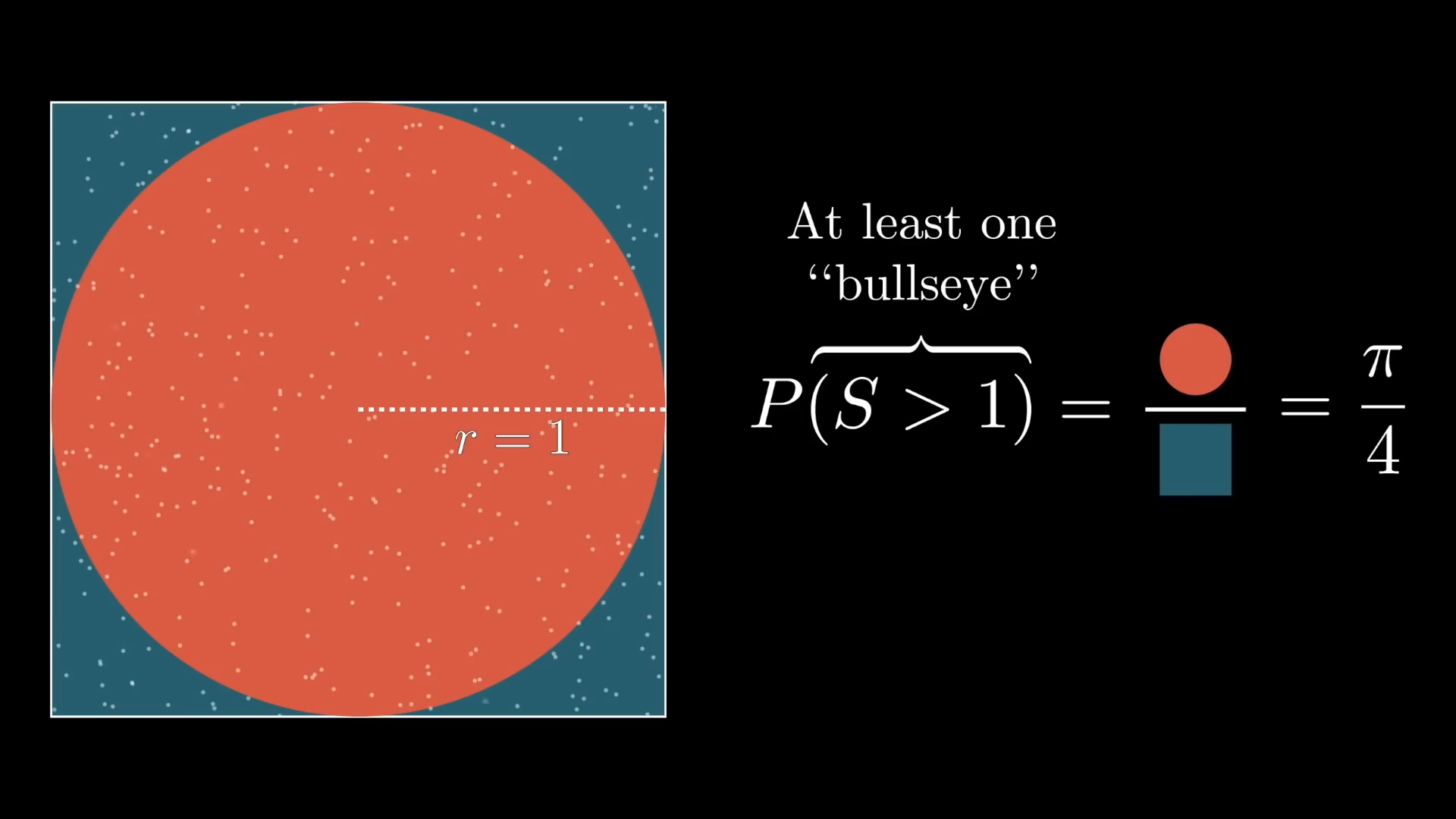

When faced with a difficult problem, we can try to get a foothold by breaking it down into smaller sub-problems. The first question we might ask is what is the probability of making the first shot? The probability can be found by dividing the area of the circle by the area of the square .

The probability of making the first shot is , so what is the probability of making the second shot? This is where things get more interesting because the probability of the second shot depends on where the first shot landed. The next radius forms a right triangle with the current radius and , so we can use the Pythagorean theorem to calculate it.

We can build a table of the radiuses and hit distances to keep track of the information.

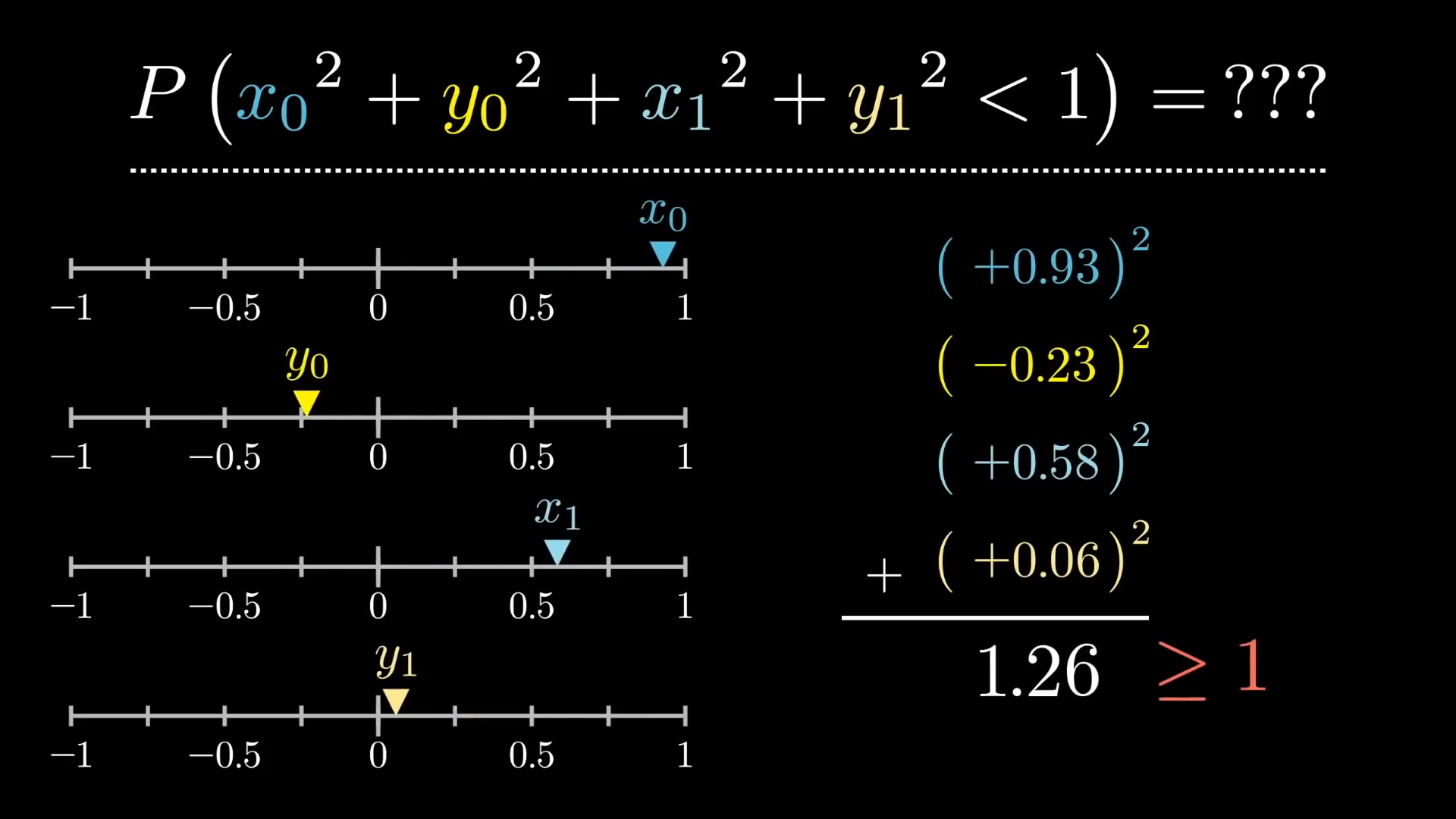

The probability the second shot goes in now depends on four numbers. It may be helpful to write out what the actual requirement is: . We can also rewrite it by taking the squares, because it doesn't change the truth value of the statement.

We're asking what is the probability that the sum of squares of four random numbers chosen in the range is less than .

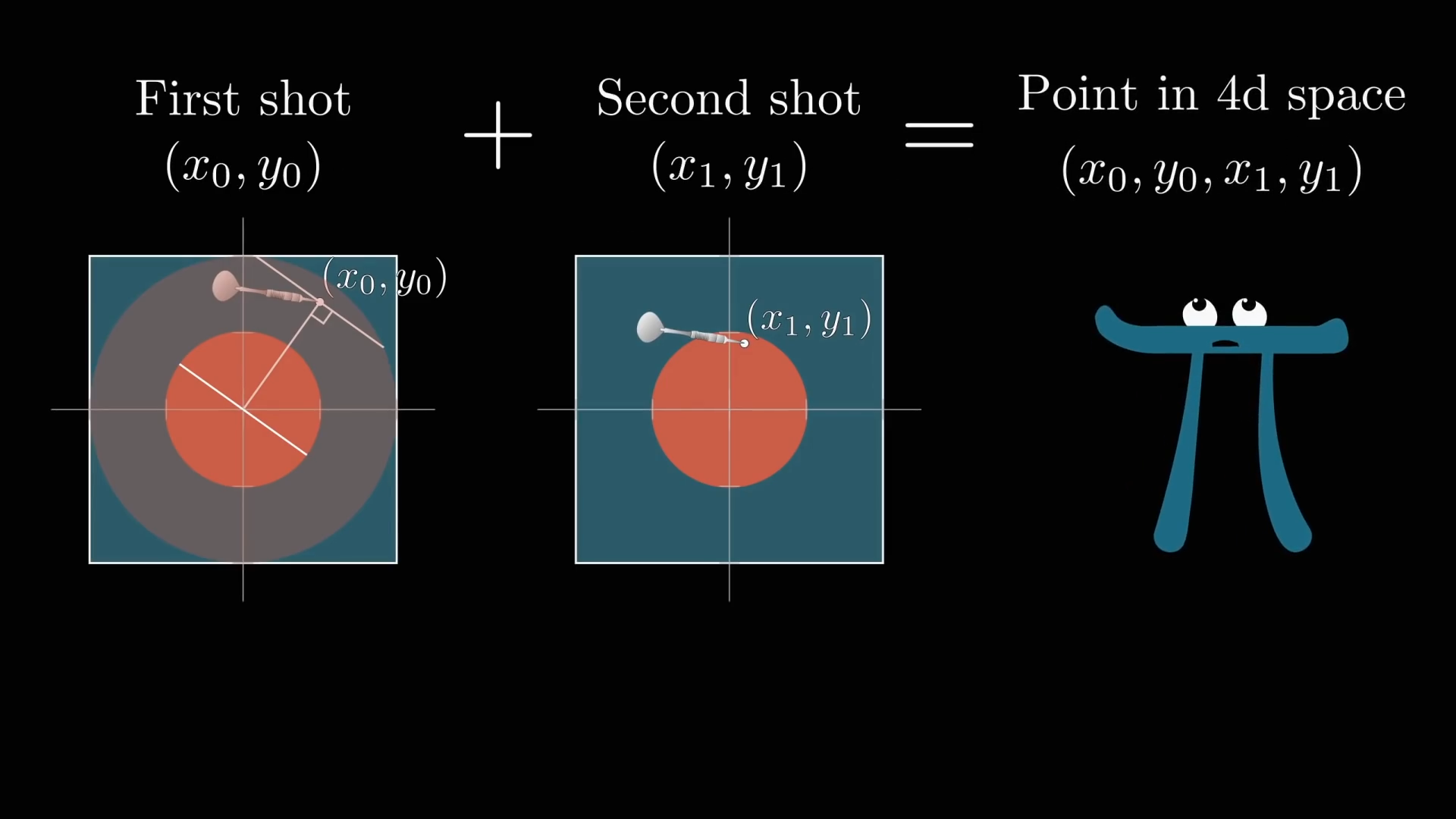

This question is a bit tricky because we could guarantee if all the numbers are less than then the sum of their squares would be less than , but if one was that doesn't necessarily throw it out because the others could be very small. We used geometric intuition for the first shot, thinking of it as a point inside or outside of a circle. Rather than thinking of the probabilistic event as two separate throws, we can also think about them as a single point in 4D space: .

Just like how choosing two random numbers and seeing if the sum of their squares is less than brought us to the area of a circle, doing the same with 4 numbers brings us to the volume of a 4D ball.

Why did we skip to 4 dimensions and not 3?

For every dart throw, we are picking an additional 2 random numbers (the x and y coordinates). This means we never consider the odd numbered dimensions.

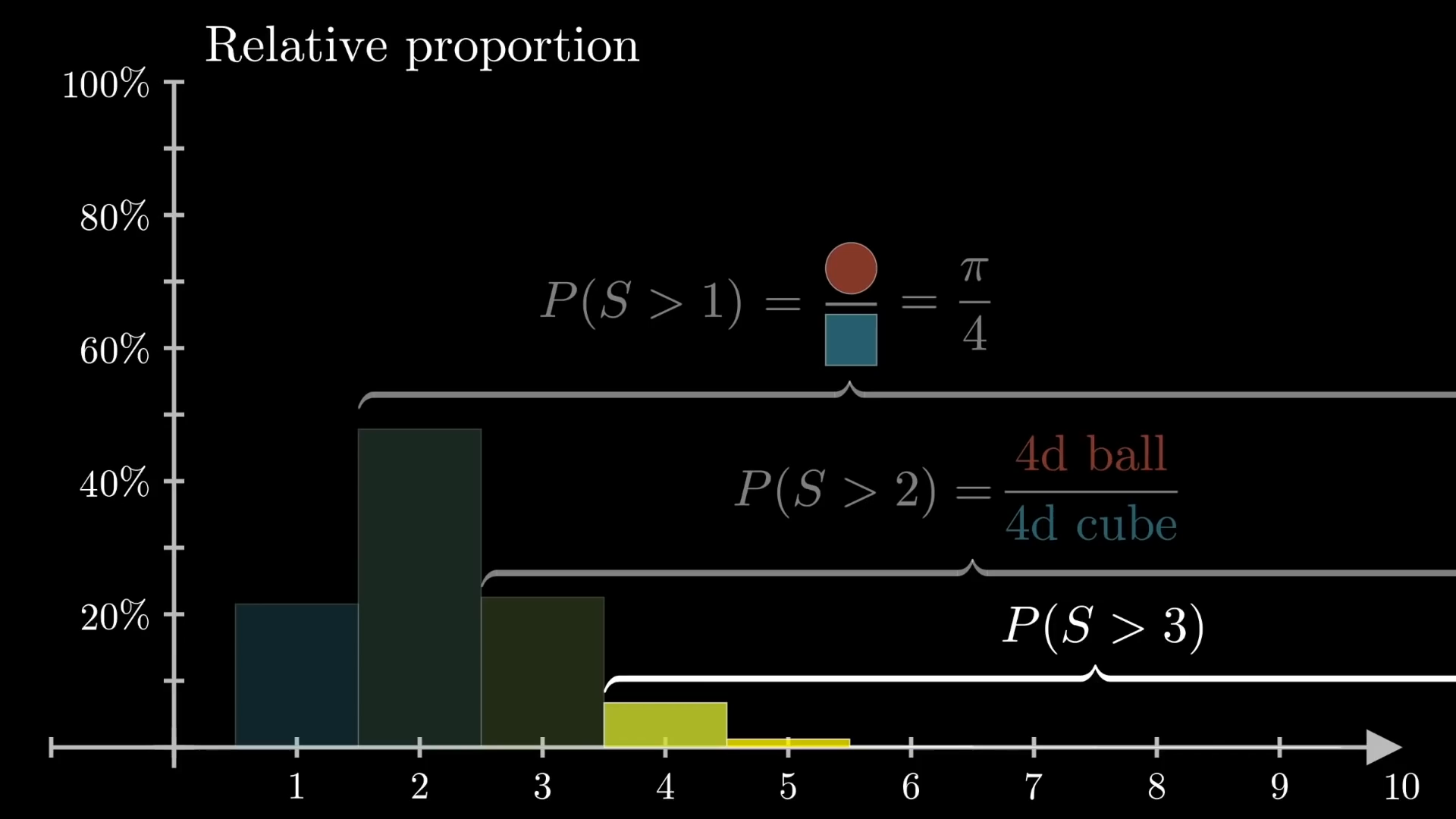

The pattern of dividing the volume of higher dimensional balls by the volume of higher dimensional cubes continues when calculating the probability of larger scores.

For we can calculate because the question is analogous to randomly choosing six numbers and having the sum of their squares be less than .

The next problem we face is how to calculate the volume of a higher dimensional ball. Luckily mathematicians have calculated them and you could look at Wikipedia's list and pick them out.

What we'd like is a general formula for the volume of an even dimensional ball:

What is the volume of a 14-dimensional unit ball?

Solution

The expected value of our dart throwing robot was defined as:

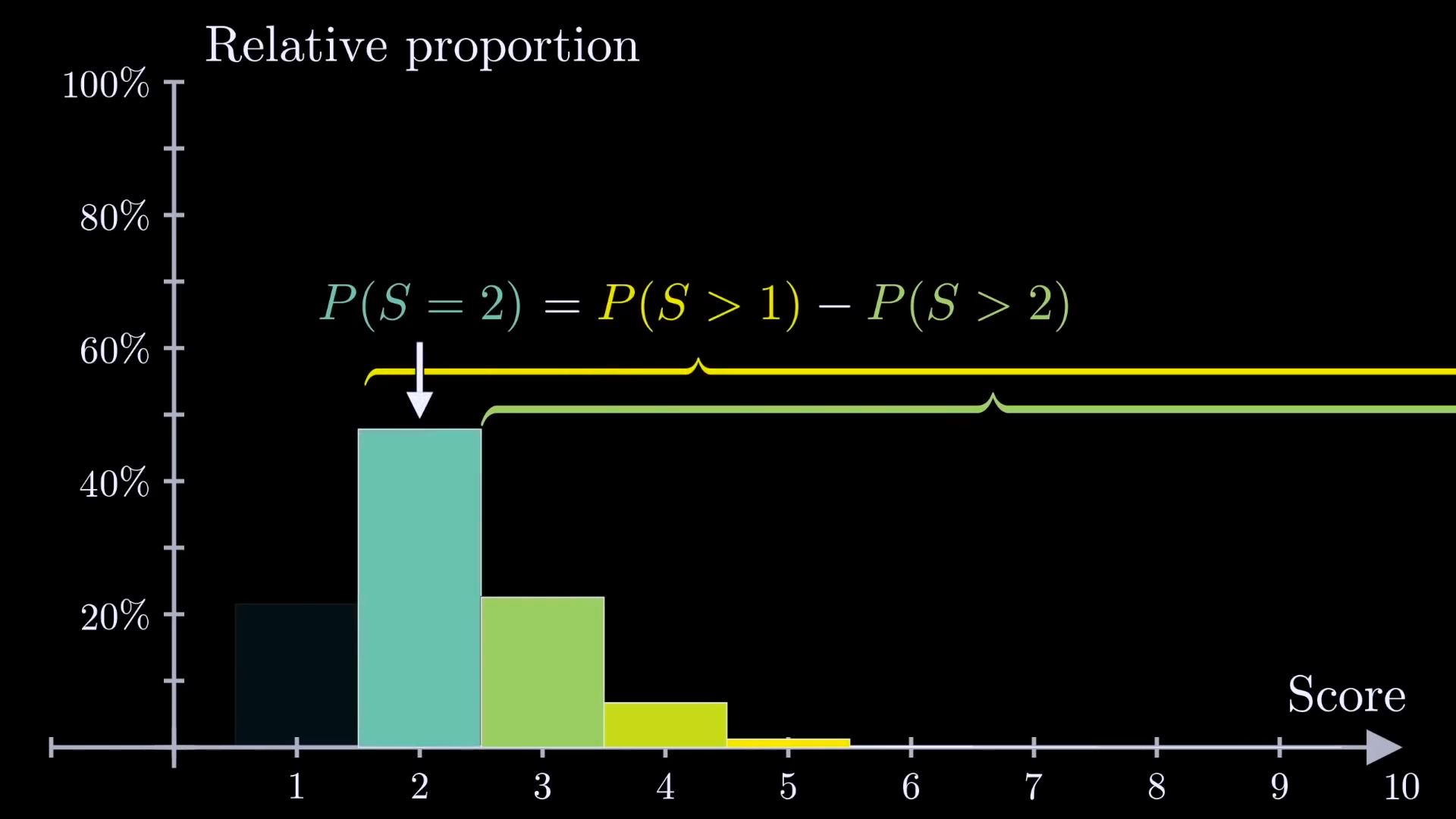

However we've been calculating probabilities in the form of greater than instead of equal to . That is completely fine because is equivalent to .

What is the value of ?

Now we can expand things out and let them collapse down.

Notice that we're subtracting off 2 of but in the next term we're adding back 3 of them. Each of these terms collapse down to just the sum of each probability:

We can begin substituting the values we have calculated so far. Since the minimum score is 1, we will always have a score above 0, so . From dividing the area of a circle by the area of a square, we know . We had previous calculated , which can also be written as . By reformatting our solutions and adding them up, we can get the formula:

This sequence of numbers is rather similar to another famous sequence: the Taylor series for powers of Euler's number is

A Taylor series is evaluated as an infinite polynomial where each term gets added together and it approaches the correct value in the limit. This particular series is the definition of and I would argue it is the healthy way to view .

Notice how our expected value is very similar to this Taylor polynomial, and the value of is . So

If our dart throwing robot played a large number of games, the average of all of its scores should be around this 2.1932 figure.

Conclusion

One of the reasons I enjoy this puzzle so much is that we are playing around with higher dimensional geometry naturally. In the middle of the puzzle we were asking what is the volume of a six dimensional ball without suggesting the universe has more dimensions or something similar. That isn't necessarily why mathematicians care about higher dimensions.

What happened is that we had six numbers and we were encoding a property of those numbers in something we like to describe geometrically. Someone else was tackling this puzzle and described how they were working through intensely difficult integrals. What they were really doing was rediscovering the volume of a 4D ball. Thinking about these higher dimensional shapes came about from a 2D plane, nothing about the dartboard was four dimensional.

Mathematicians will often describe manifolds in four dimensions or how the Poincaré conjecture has been solved for everything but four dimensions. But a common misconception people will have is that mathematicians don't actually care about moving in four dimensions, it is about encoding quadruplets of points.

Another reason why this puzzle is beautiful is it helps builds a healthier relationship with . The Taylor series is more important than the number itself, it helps explain why is its own derivative, why , and many other abstract concepts that go beyond simple repeated multiplication.

Another nice puzzle which distills down the essence of without involving circles and complicating the answer with is described below.