The hardest problem on the hardest test

The problem

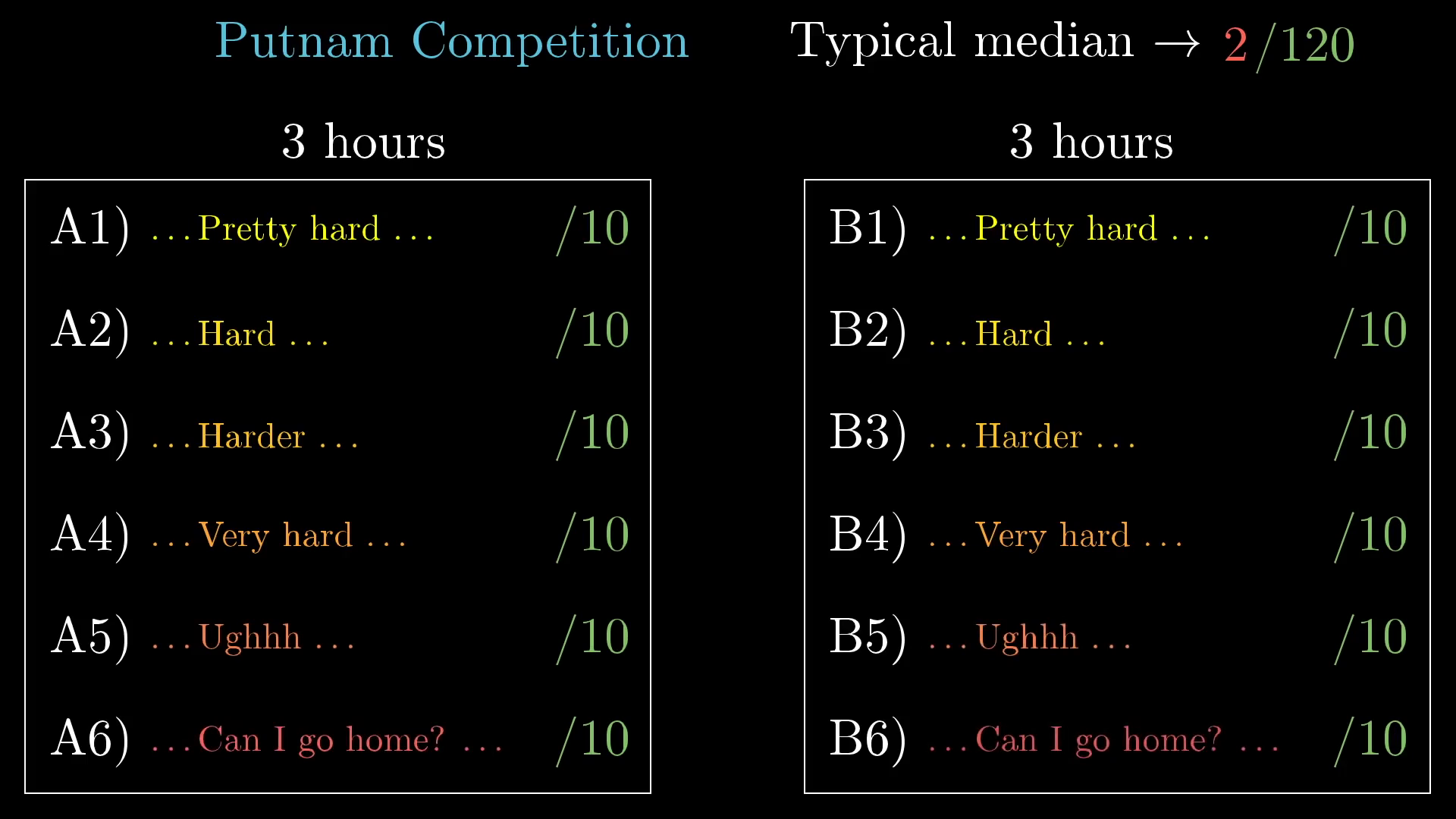

There's a famous math competition for undergraduate students known as the Putnam. It's 6 hours long and consists of 12 questions, broken up into two different 3-hour sessions over two days. Each question being scored on a 1-10 scale, so the highest possible score is 120.

And yet, despite the fact that the only students taking it each year are those who are clearly already pretty into math, given that they opt into such a test, the median score tends to be around 1 or 2.

It's a hard test

For each day the six problems tend to increase in difficulty, ranging from pretty difficult to exceedingly challenging. But of course, difficulty is sometimes in the eye of the beholder.

But here's the thing about those 5's and 6's. Even though they're positioned as the hardest problems on a famously hard test, quite often these are the ones with the most elegant solutions available, often involving some subtle shift in perspective that transforms it from challenging to simple.

Here I'll share with you one problem which came up as question A6 on the 1992 Putnam exam. Rather than just jumping straight to the solution, which in this case will be surprisingly short, let's take the time to walk through how you might stumble upon the solution yourself. This story is more about the problem-solving process than the particular problem used to exemplify it.

Here's the question:

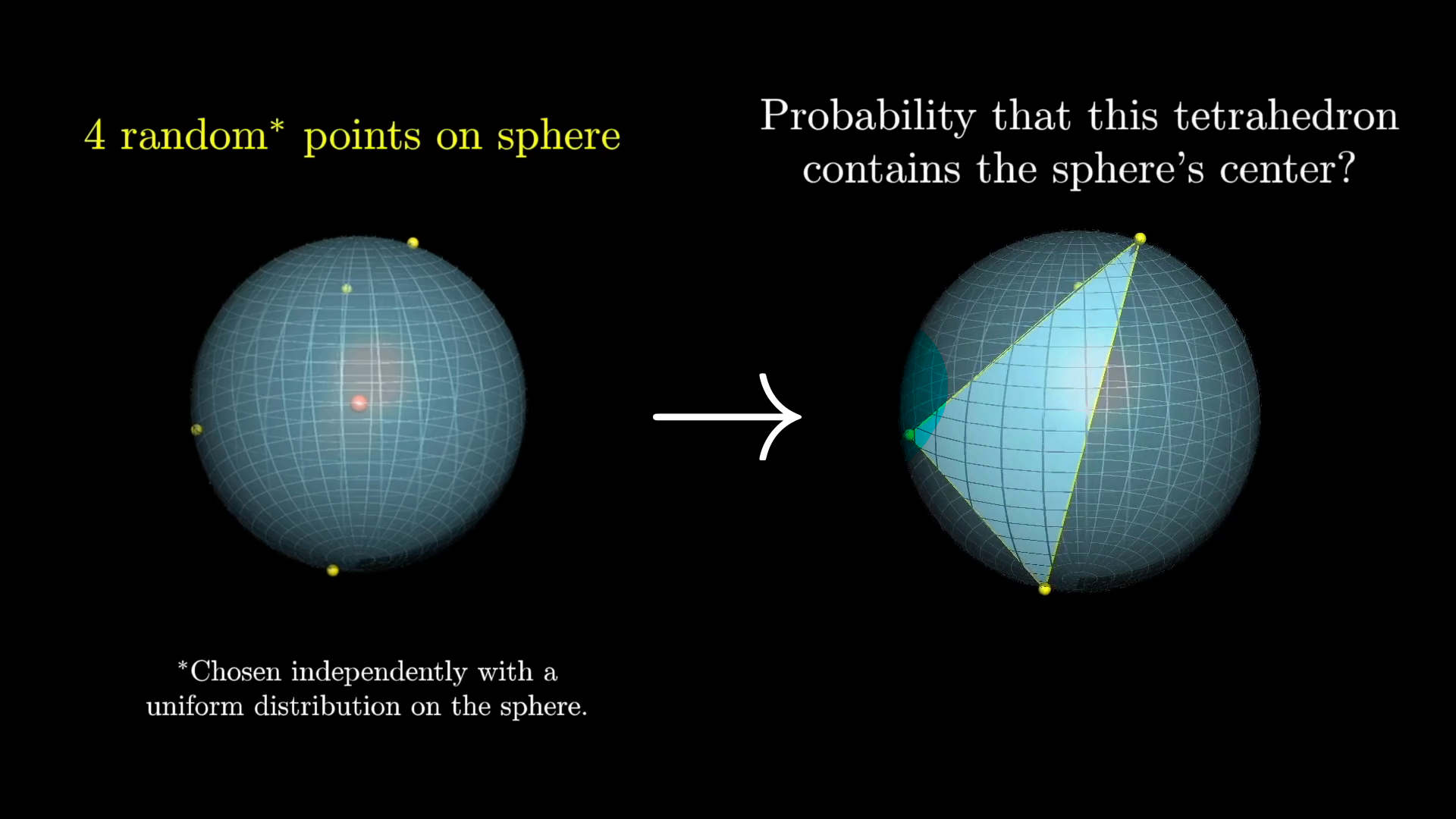

Four points are chosen at random on the surface of a sphere. What is the probability that the center of the sphere lies inside the tetrahedron whose vertices are at the four points? (It is understood that each point is independently chosen relative to a uniform distribution on the sphere.)

Take a moment to digest the question. You might start thinking about which of these tetrahedra contain the sphere's center, which ones don't, and how you might systematically distinguish the two.

How do you approach a problem like this? Where do you even start? Well, it's often a good idea to think about simpler cases, so let's bring things down into two dimensions.

The two-dimensional case

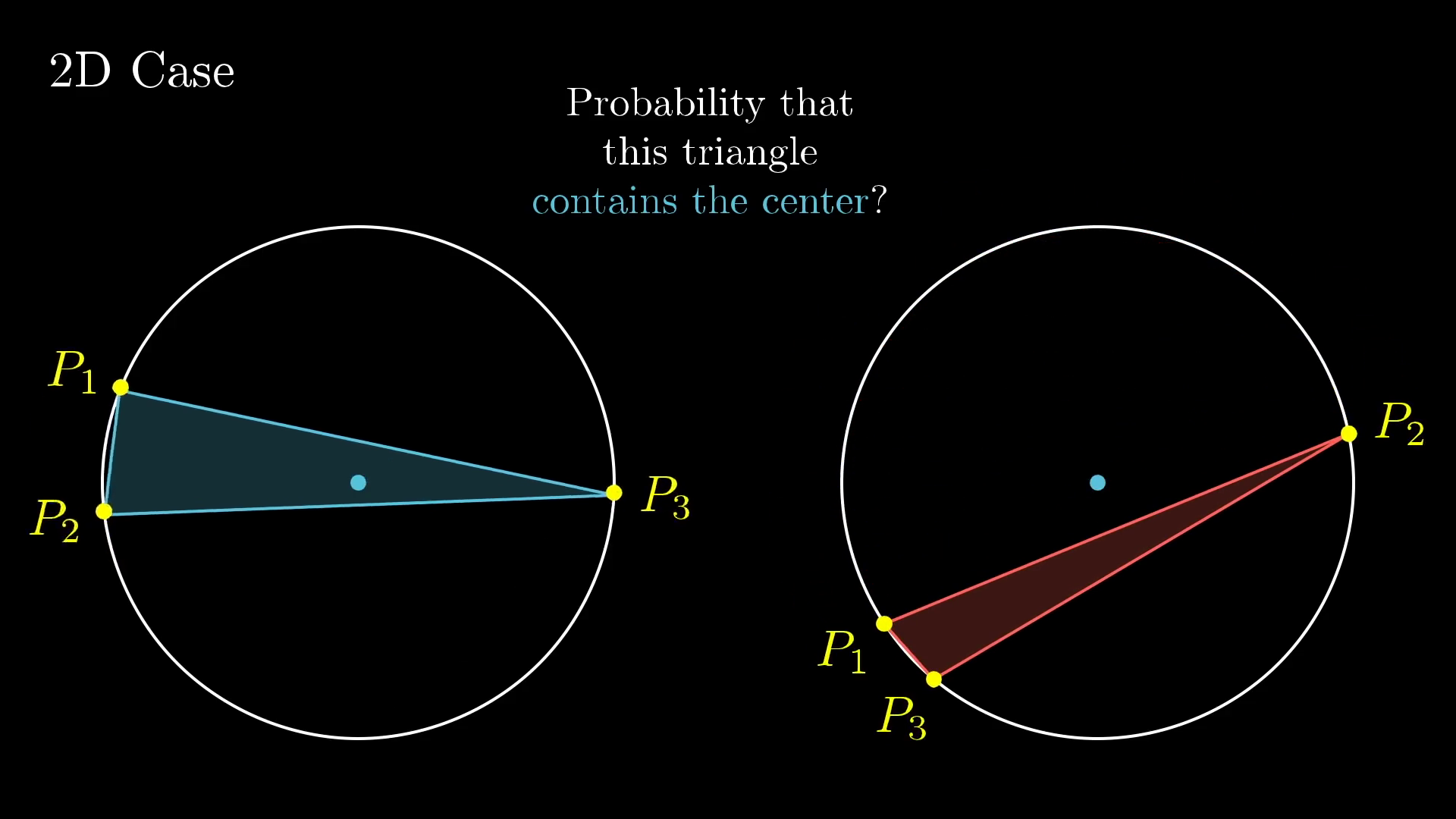

Suppose you choose three random points on a circle. It's always helpful to name things, so let's call these fellows , , and . What's the probability that the triangle formed by these points contains the center of the circle?

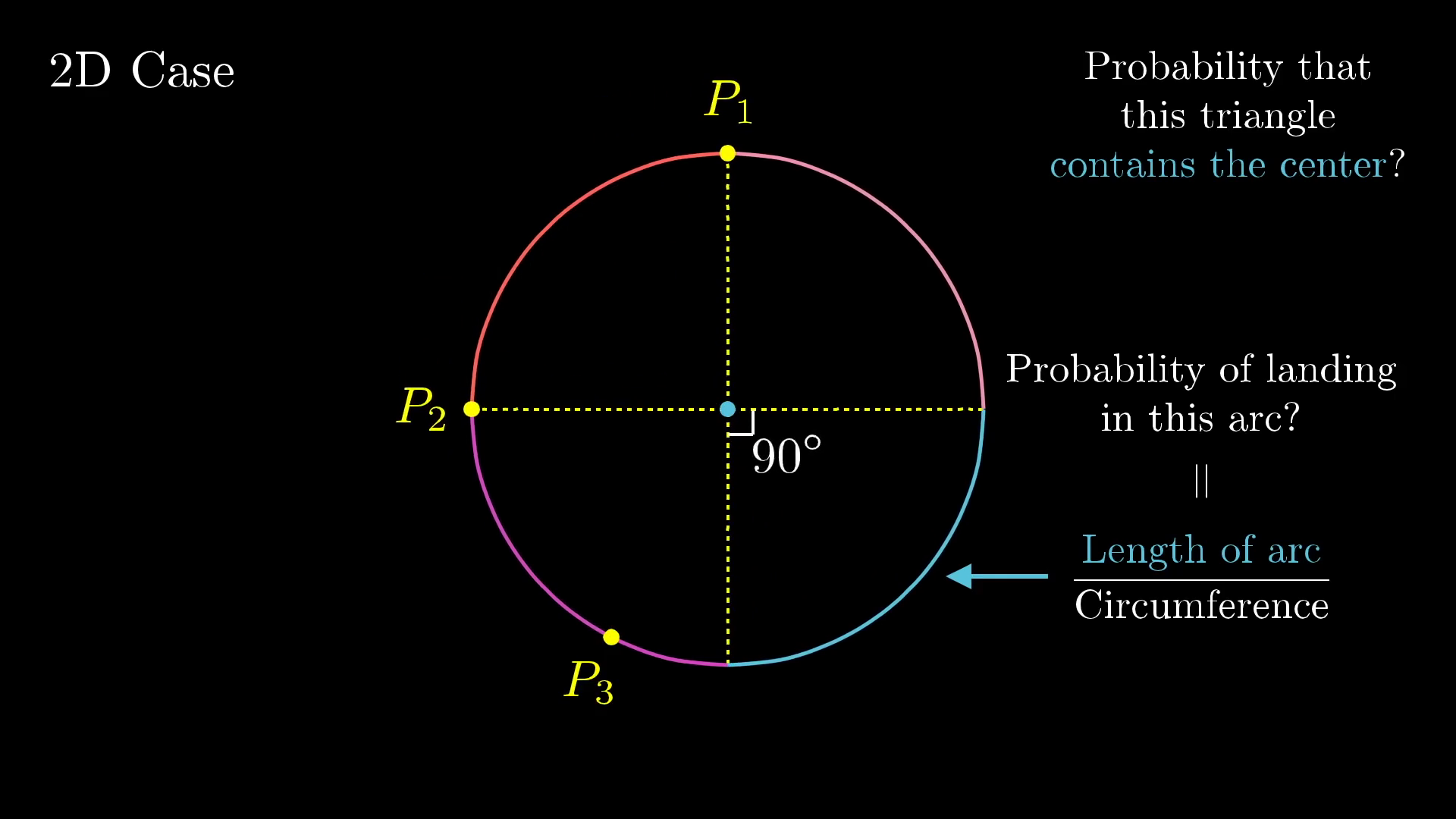

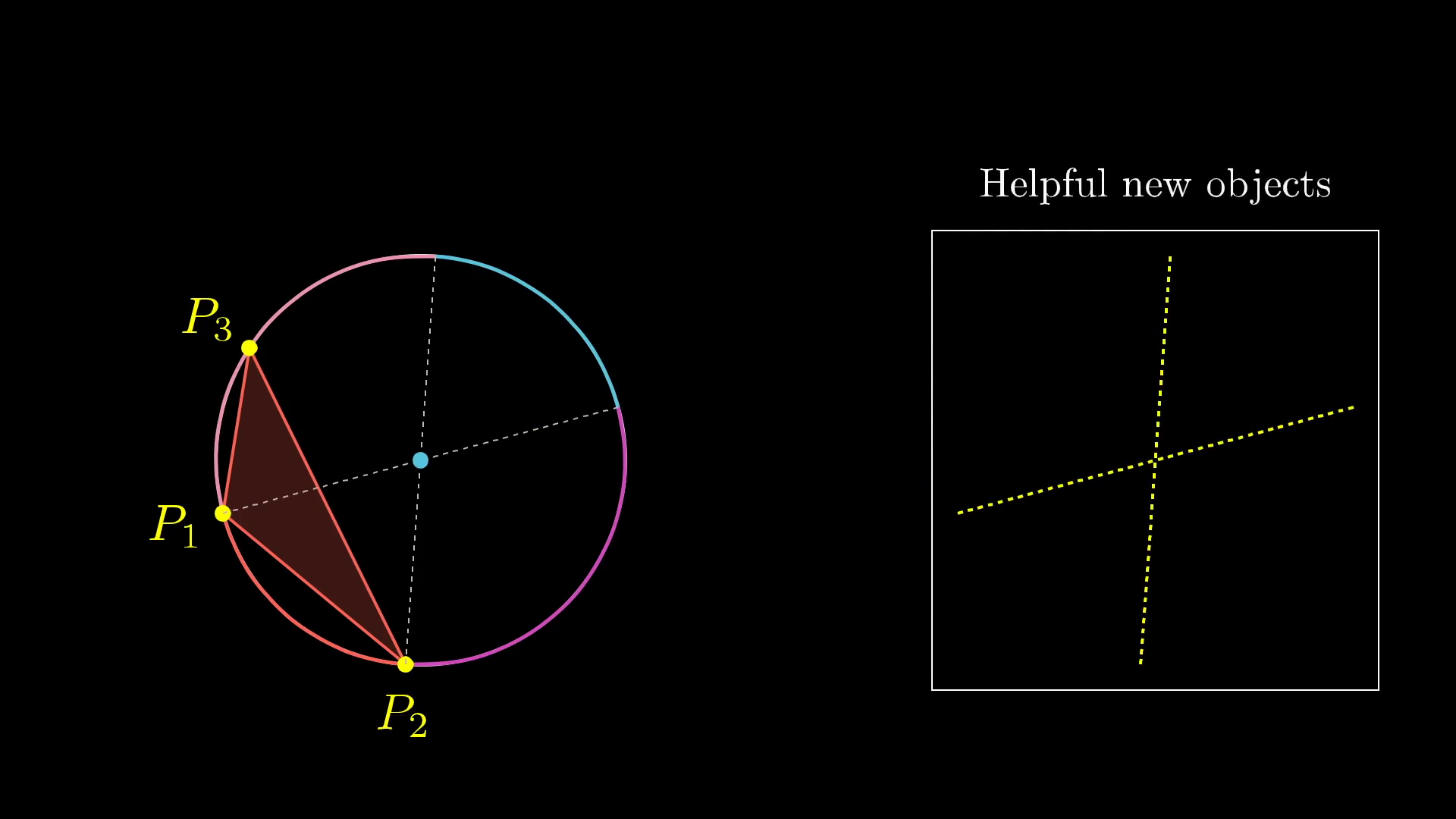

This is still a hard question, so you should ask yourself if there's a way to simplify the question even further. We still need a foothold, something to build up from. Maybe you imagine fixing and in place, only letting vary. In doing this, you might notice that there's special region, a certain arc, where when is in that arc, the triangle contains the circle's center.

Specifically, if you draw a lines from and through the center, these lines divide the circle into 4 different arcs. If happens to be in the arc opposite and , the triangle will contain the center. Otherwise, you're out of luck.

It's certainly easier to visualize now, but can you answer the question?

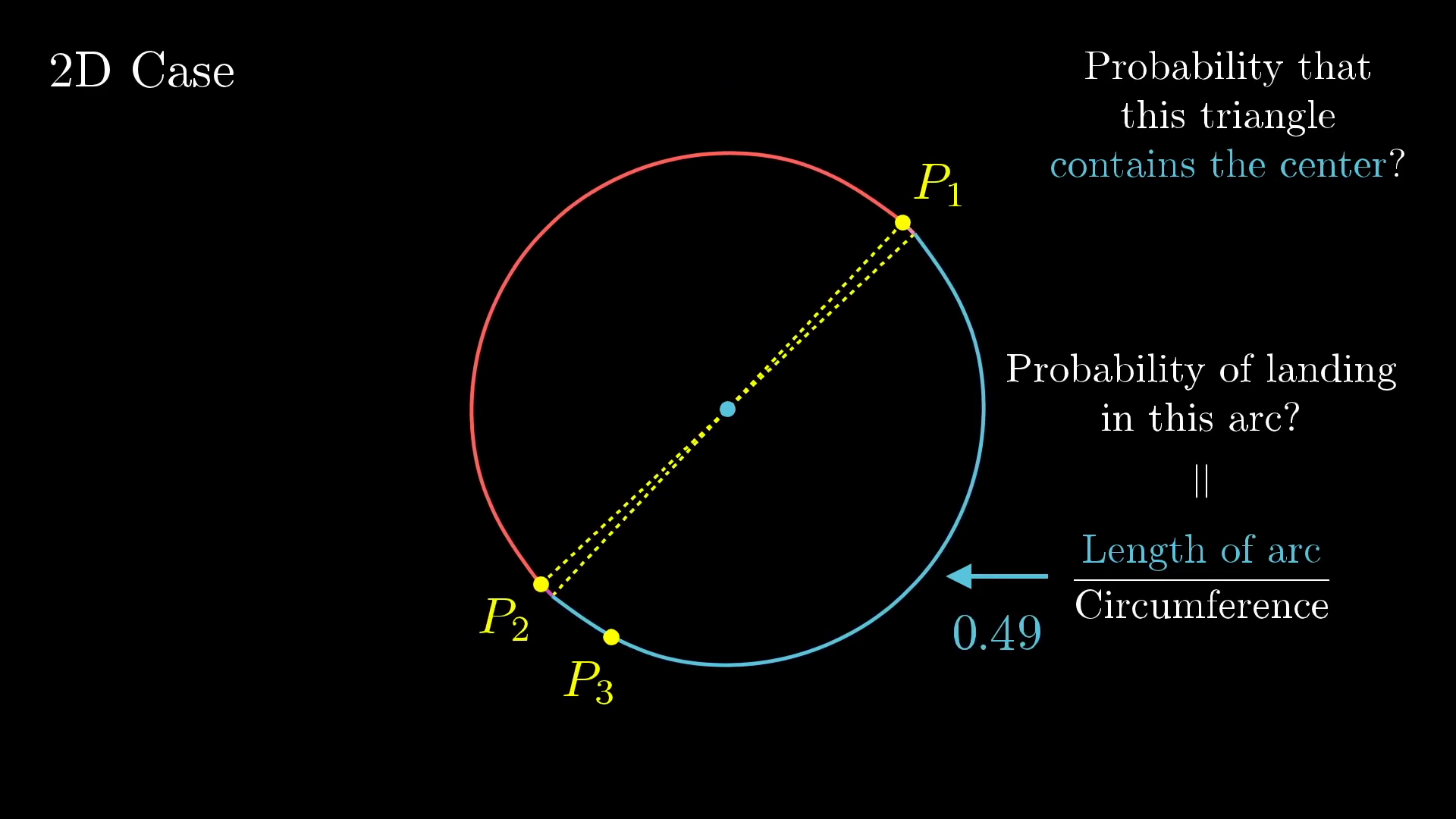

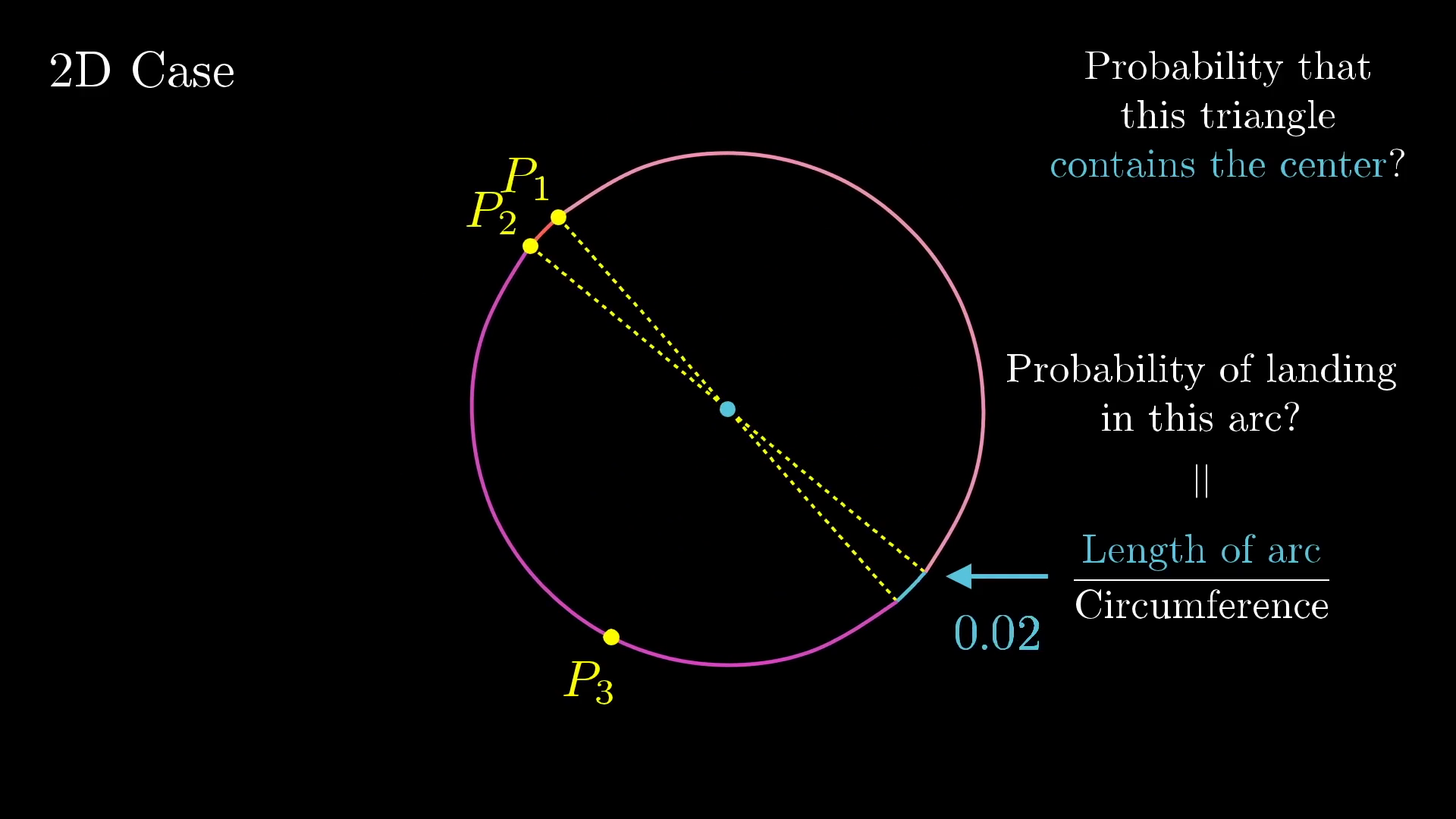

If and are fixed in place on the circle, with an arc length between them, and is a point chosen randomly on the circle (with a uniform distribution), what is the probability that the triangle contains the center of the circle?

So what proportion of the circle does this arc take up? That depends on the first two points. If they are 90 degrees apart from each other, for example, the relevant arc is of the circle.

But if those two points are farther apart, the proportion might be closer to 1/2.

If they are really close, that proportion might be closer to 0.

If and are chosen randomly, with every point on the circle being equally likely, what's the average size of the relevant arc?

Maybe you imagine fixing in place, and considering all the places that might be.

All of the possible angles between these two lines, every angle from 0 degrees up to 180 degrees is equally likely, so every proportion between 0 and 0.5 is equally likely, making the average proportion 0.25. Since the average size of this arc is this full circle, the average probability that the third point lands in it is , meaning the overall probability of our triangle containing the center is .

The three-dimensional case

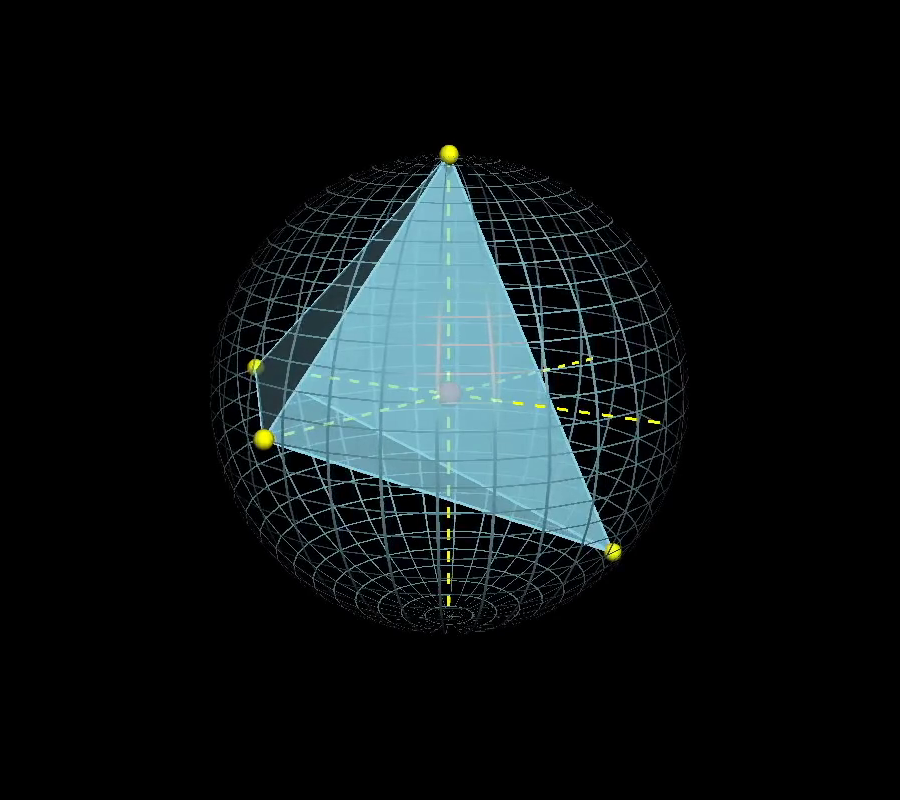

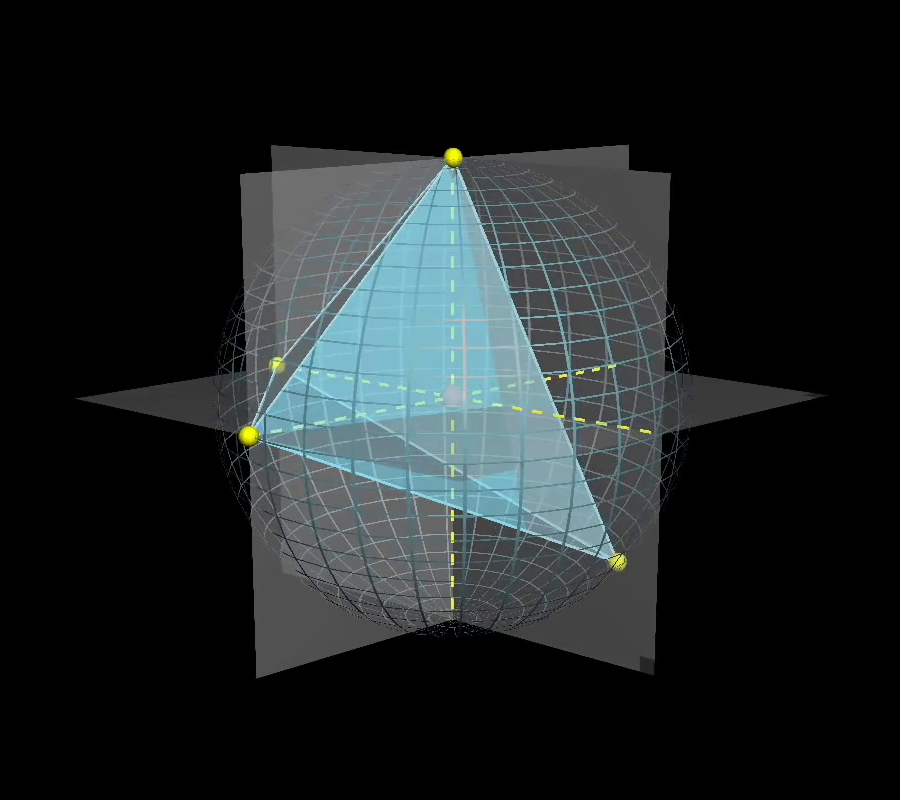

Great! Can we extend this to the 3d case? If you imagine 3 of your 4 points fixed in place, which points of the sphere can that 4th point be on so that our tetrahedron contains the sphere's center? As before, let's draw some lines from each of our first 3 points through the center of the sphere.

And it's also helpful if we draw the planes determined by any pair of these lines.

These planes divide the sphere into 8 different sections, each of which is a sort of spherical triangle. Our tetrahedron will only contain the center of the sphere if the fourth point is in the section on the opposite side of our three points.

Unlike the 2d case, it's rather difficult to think about the average size of this section as we let our initial 3 points vary. Those of you with some multivariable calculus under your belt might think to try a surface integral. And by all means, pull out some paper and give it a try, but it's not easy. And of course it should be difficult, this is the 6th problem on a Putnam!

The shift in perspective

But let's back up to the 2d case, and contemplate if there's a different way to think about it. This answer we got, , is suspiciously clean and raises the question of what that 4 represents. One of the main reasons I wanted to cover this topic is that what's about to happen carries a broader lesson for mathematical problem-solving.

The lines that we drew from and through the origin made the problem easier to think about. In general, whenever you've added something to your problem setup which makes things conceptually easier, see if you can reframe the entire question in terms of the thing you just added.

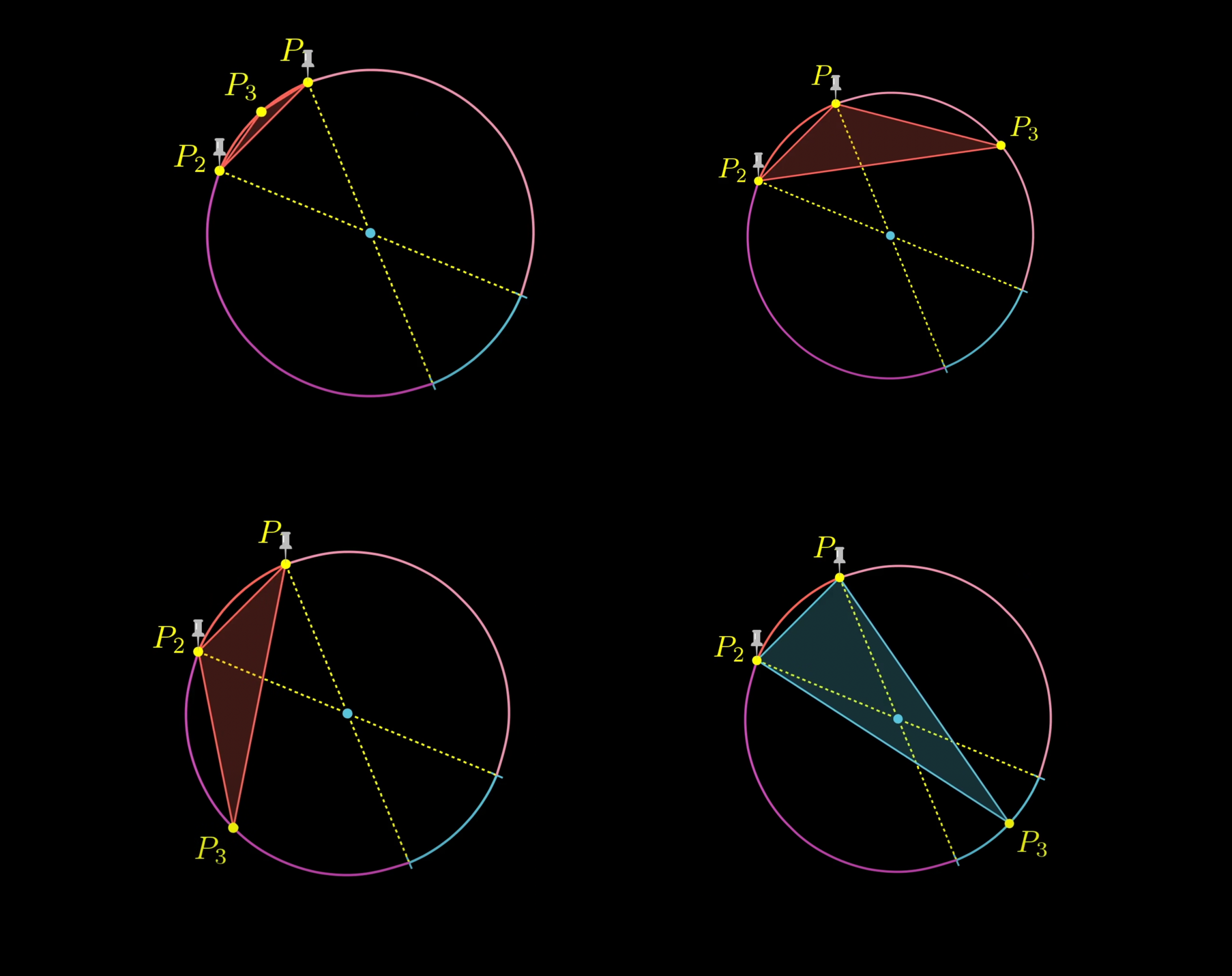

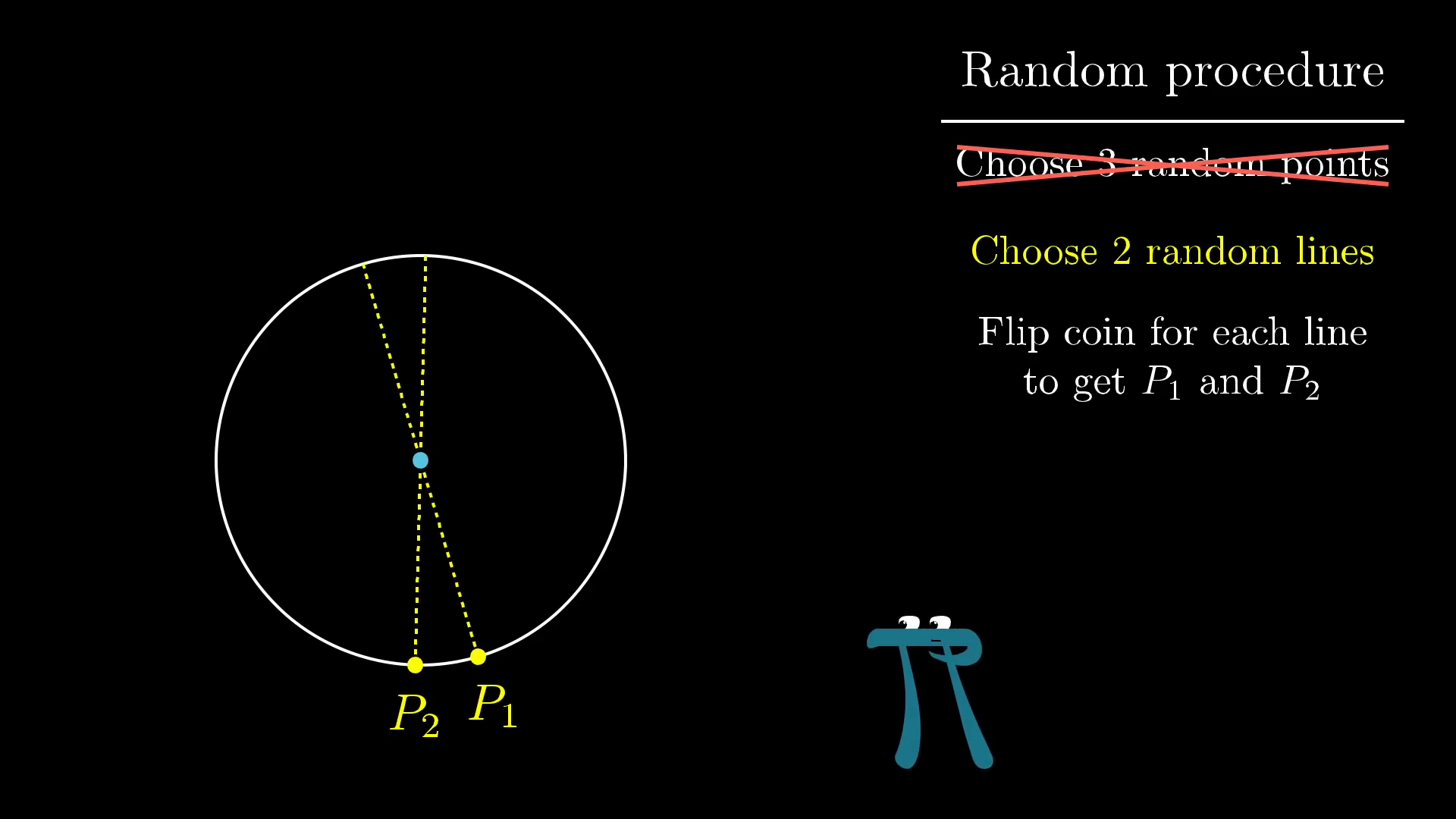

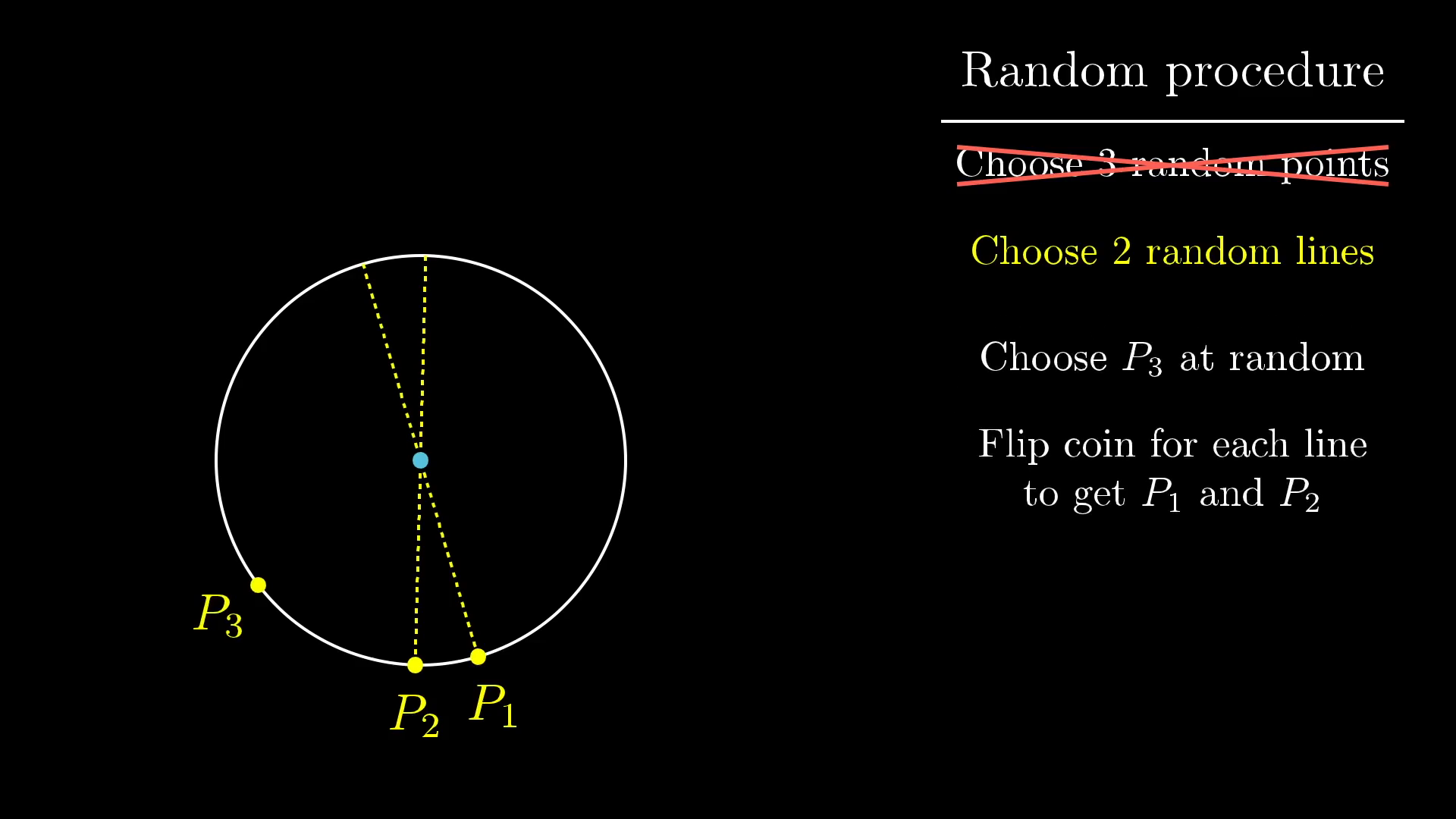

In this case, rather than thinking about choosing 3 points randomly, start by saying choose two random lines that pass through the circle's center. For each line, there are two possible points they could correspond to, so flip a coin for each to choose which of those will be and .

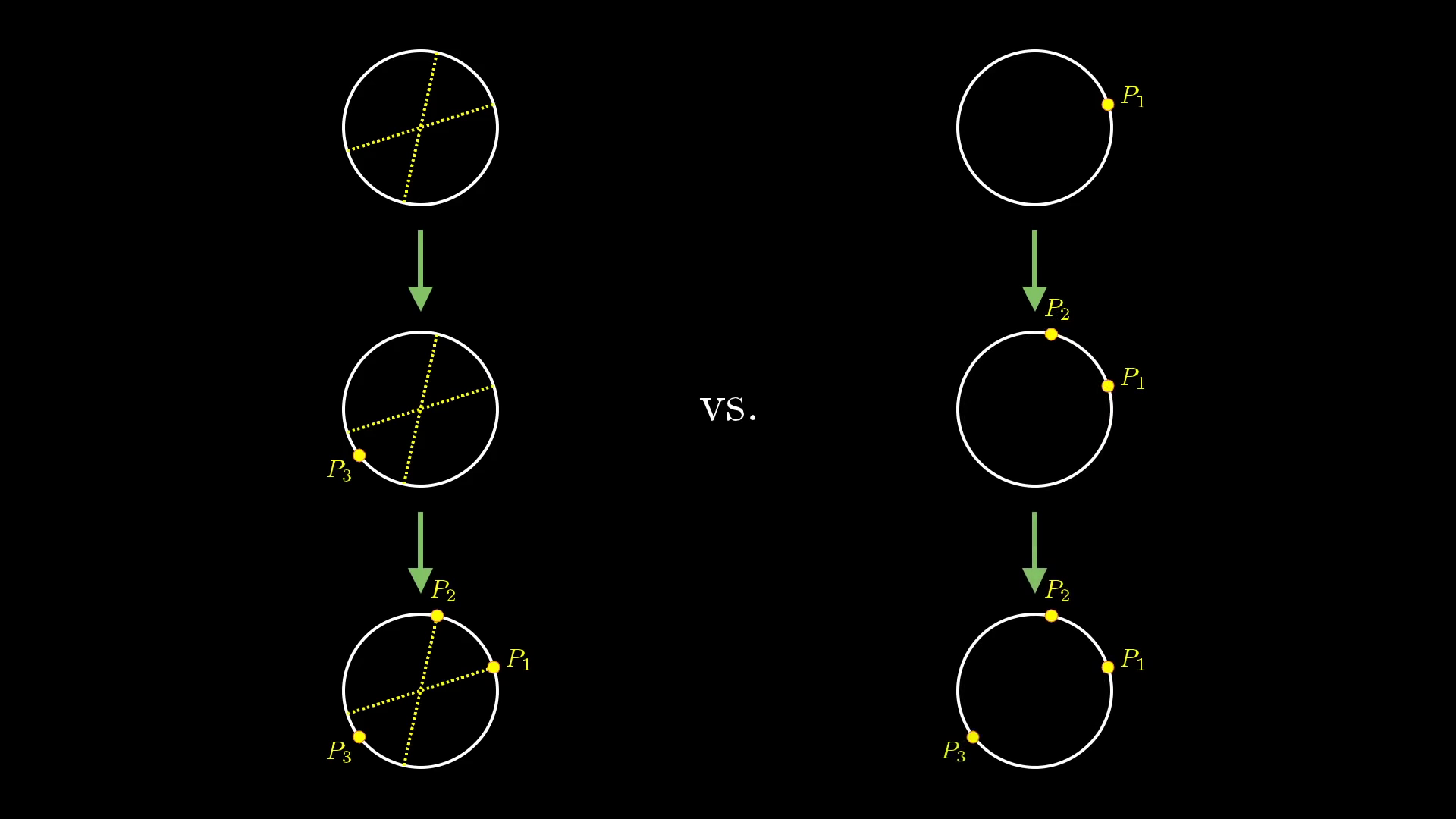

Choosing a random line then flipping a coin like this is the same as choosing a random point on the circle, with all points being equally likely, and at first it might seem needlessly convoluted way to describe choosing two random points. But by making those lines the starting point of our random process things actually become easier.

We'll still think about as just being a random point on the circle, but imagine that it was chosen before you do the two coin flips.

You see, once the two lines and a random point have been chosen, there are four possibilities for where and end up, based on the coin flips, each one of which is equally likely. But one and only one of those outcomes leaves and on the opposite side of the circle as , with the triangle they form containing the center. So no matter what those two lines and turned out to be, it's always a chance that the coin flips will leave us with a triangle containing the center.

That's very subtle. Just by reframing how we think of the random process for choosing these points, the answer popped in a different way from before. And importantly, this style of argument generalizes seamlessly to 3 dimensions.

Applying the shift to three dimensions

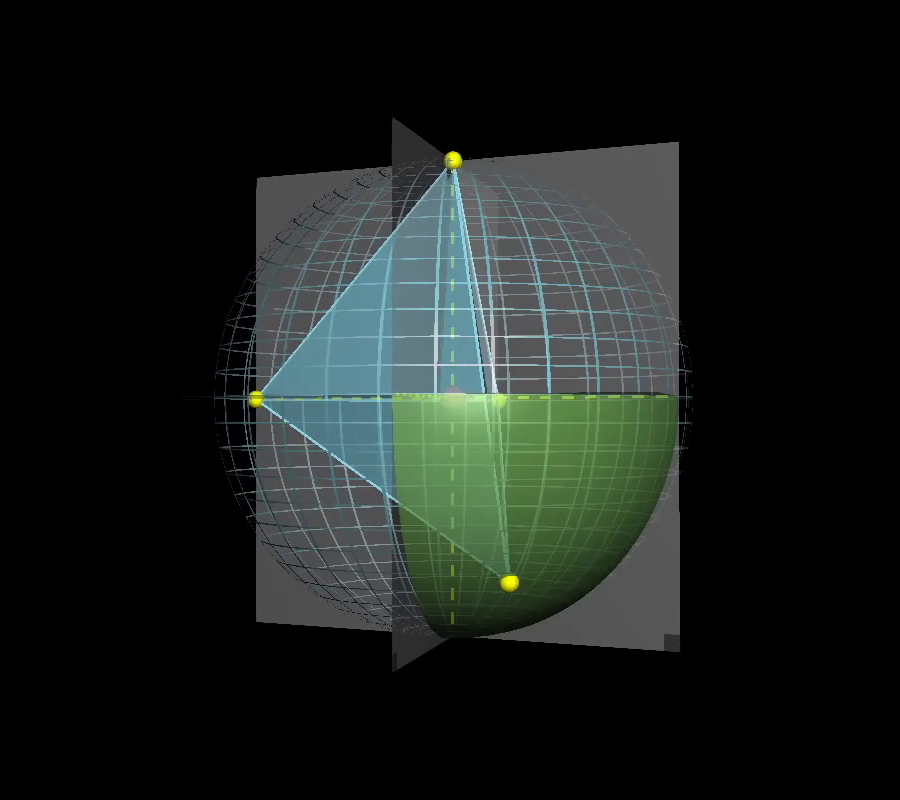

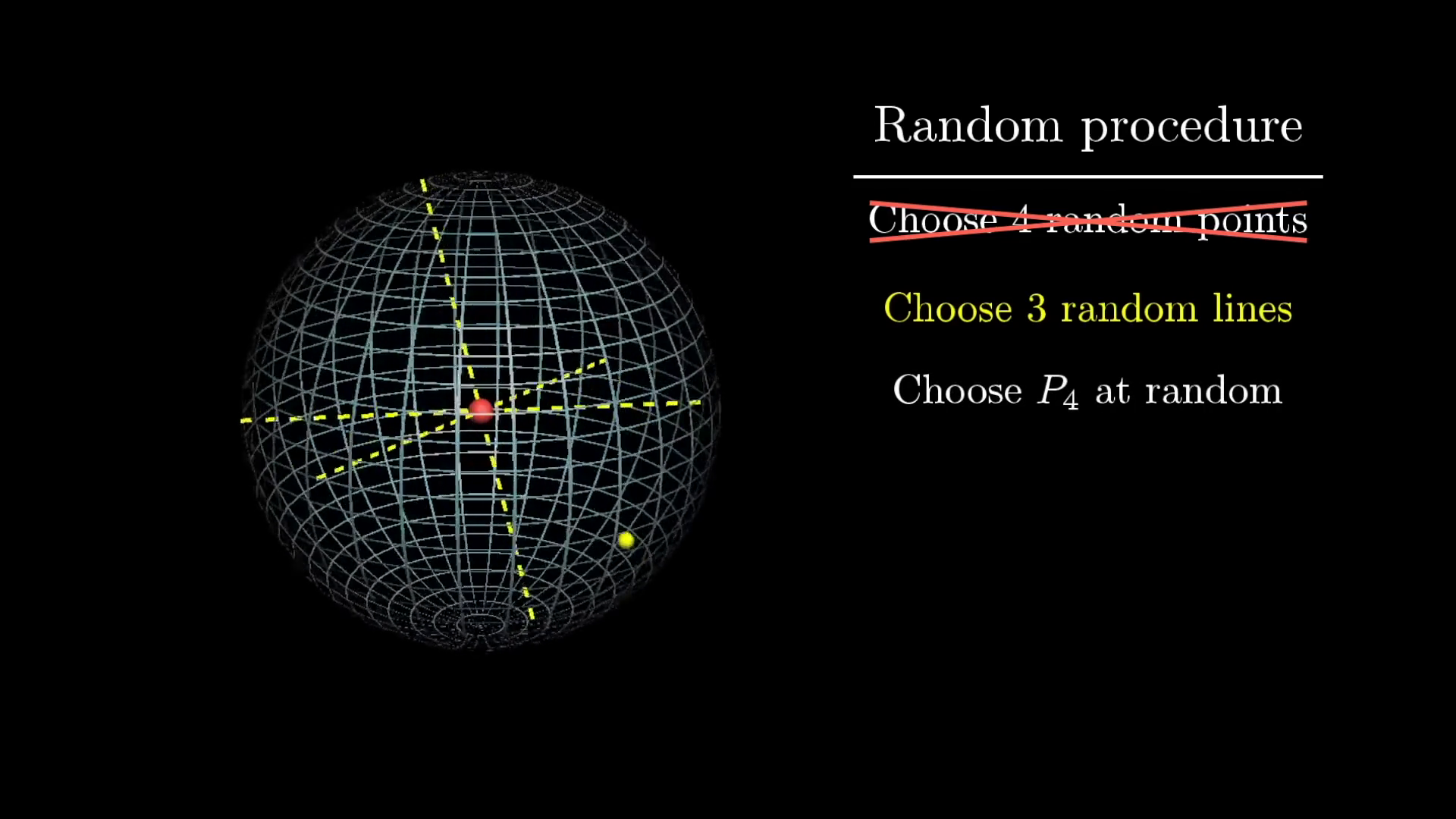

Again, instead of starting off by picking 4 random points, imagine choosing 3 random lines through the center, and then a random point for .

That first line passes through the sphere at 2 points, so flip a coin to decide which of those two points is . Likewise, for each of the other lines flip a coin to decide where and end up.

There are 8 equally likely outcomes of these coin flips, but one and only one of these outcomes will place , , and on the opposite side of the center from . So only one of these 8 equally likely outcomes gives a tetrahedron containing the center, meaning our final answer is .

Isn't that elegant?

This is a valid solution, but admittedly the way I've stated it so far rests on some visual intuition. Here is a more formal write-up of this same solution in the language of linear algebra by Ralph Howard and Paul Sisson, if you're curious. This is common in math, where having the key insight and understanding is one thing, but having the relevant background to articulate this understanding more formally is almost a separate muscle entirely, one which undergraduate math students spend much of their time building up.

The takeaway

The important lesson here is not the specific solution; after all who cares about random tetrahedra in a sphere? Instead take note of the two key problem-solving tactics that led us to the solution, which most certainly carry over to many problems that do matter.

- Continue asking simpler versions of the question until you can get some foothold.

- If some added construct proves to be useful, see if you can reframe the whole question around that new construct.

Thanks

Special thanks to those below for supporting the original video behind this post, and to current patrons for funding ongoing projects. If you find these lessons valuable, consider joining.