Euler's formula with introductory group theory

Euler's Formula via Group Theory

In this article we’ll be looking at Euler’s formula. This famous equation is a common topic in high school math, but the idea here is to take certain concepts from a field of math, called “group theory,” and show how they give Euler’s formula a much richer interpretation than a mere association between numbers.

The idea we’ll be exploring isn’t even a proof, it is really just an intuition. The reason I want to put out the group theory view is not because I think it’s better than other explanations, it's because it has the chance to change how you think about numbers, and how you think about algebra.

Square Group

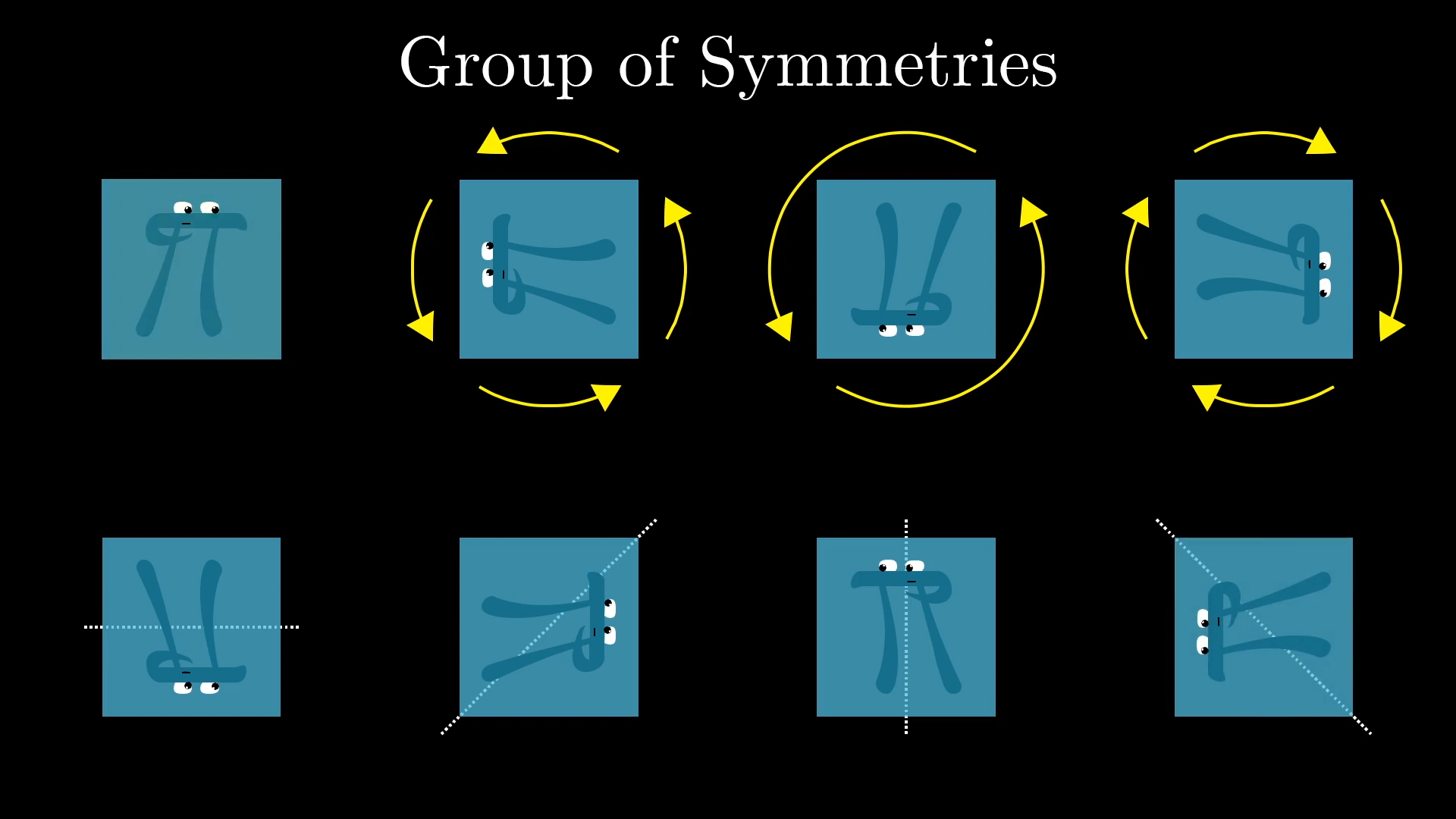

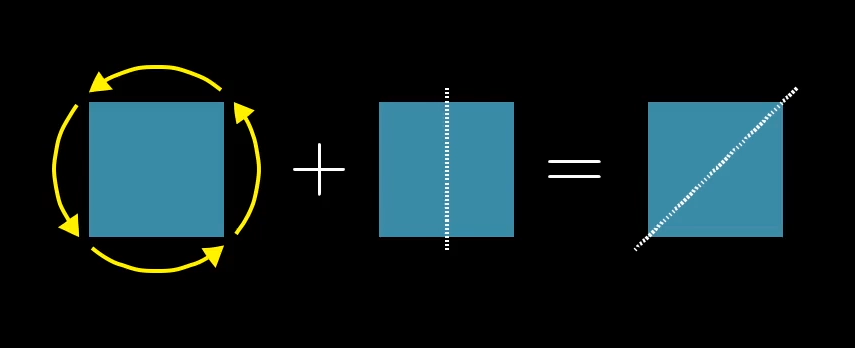

Group theory is all about studying the nature of symmetry. For example, a square is a very symmetric shape, but what do we actually mean by that? One way to answer that is to ask about what actions you can take on the square that leave it looking indistinguishable from how it started.

One action we can take is to rotate it 90 degrees counterclockwise, and it looks identical to how it started. You could also flip it around a vertical line, and it still looks identical. In fact, the thing about such perfect symmetry is that it’s hard to keep track of what action has actually been taken, so to help I’ll stick a little on here.

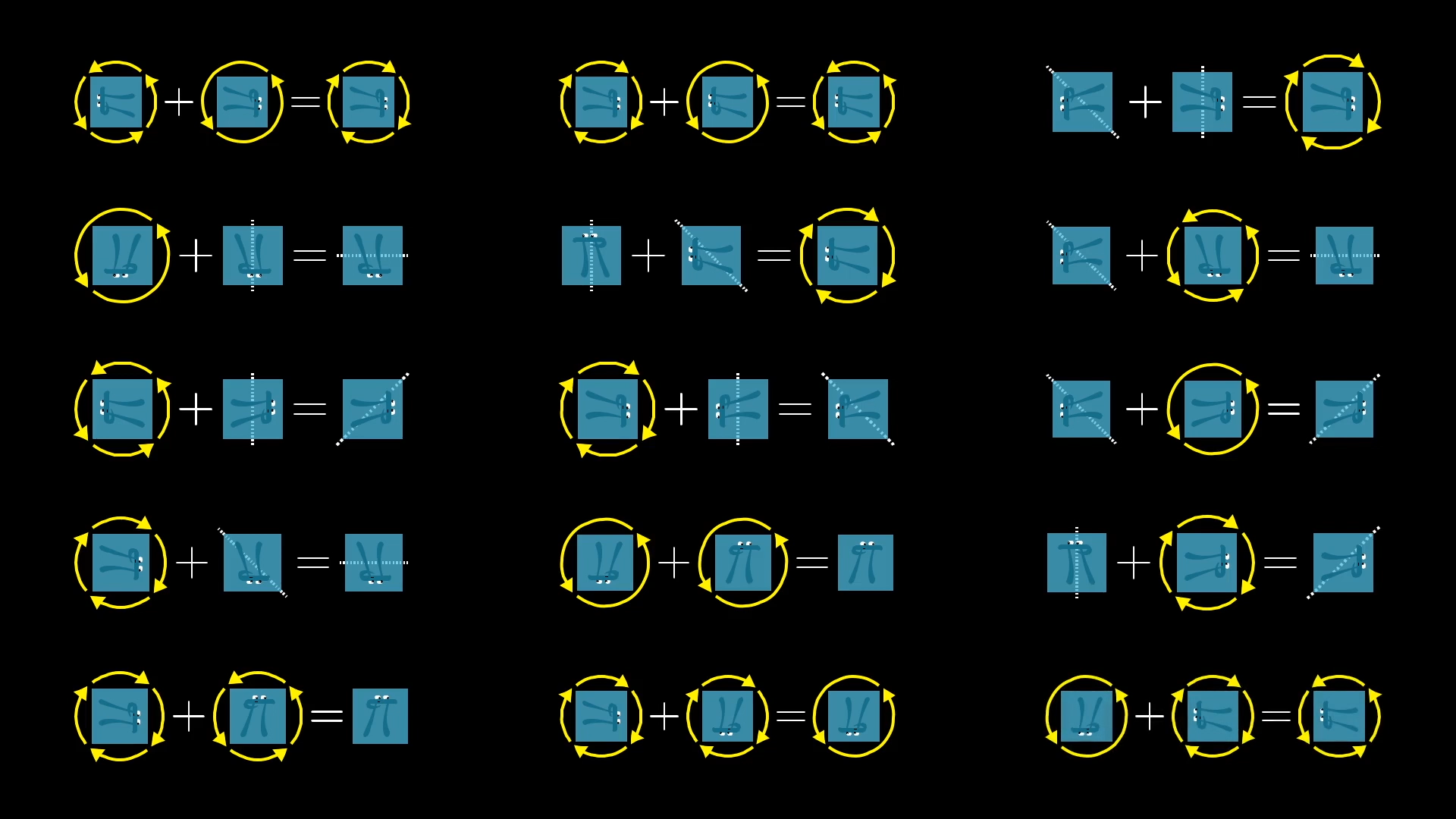

We call each of these actions a “symmetry” of the square, and all the symmetries together make up a “group of symmetries”, or “group” for short. This particular group consists of 8 symmetries: There’s the action of doing nothing, which we count, plus 3 rotations, and then 4 ways to flip it over. This group of 8 symmetries actually has a special name: the “Dihedral group of degree 4.”

Circle Group

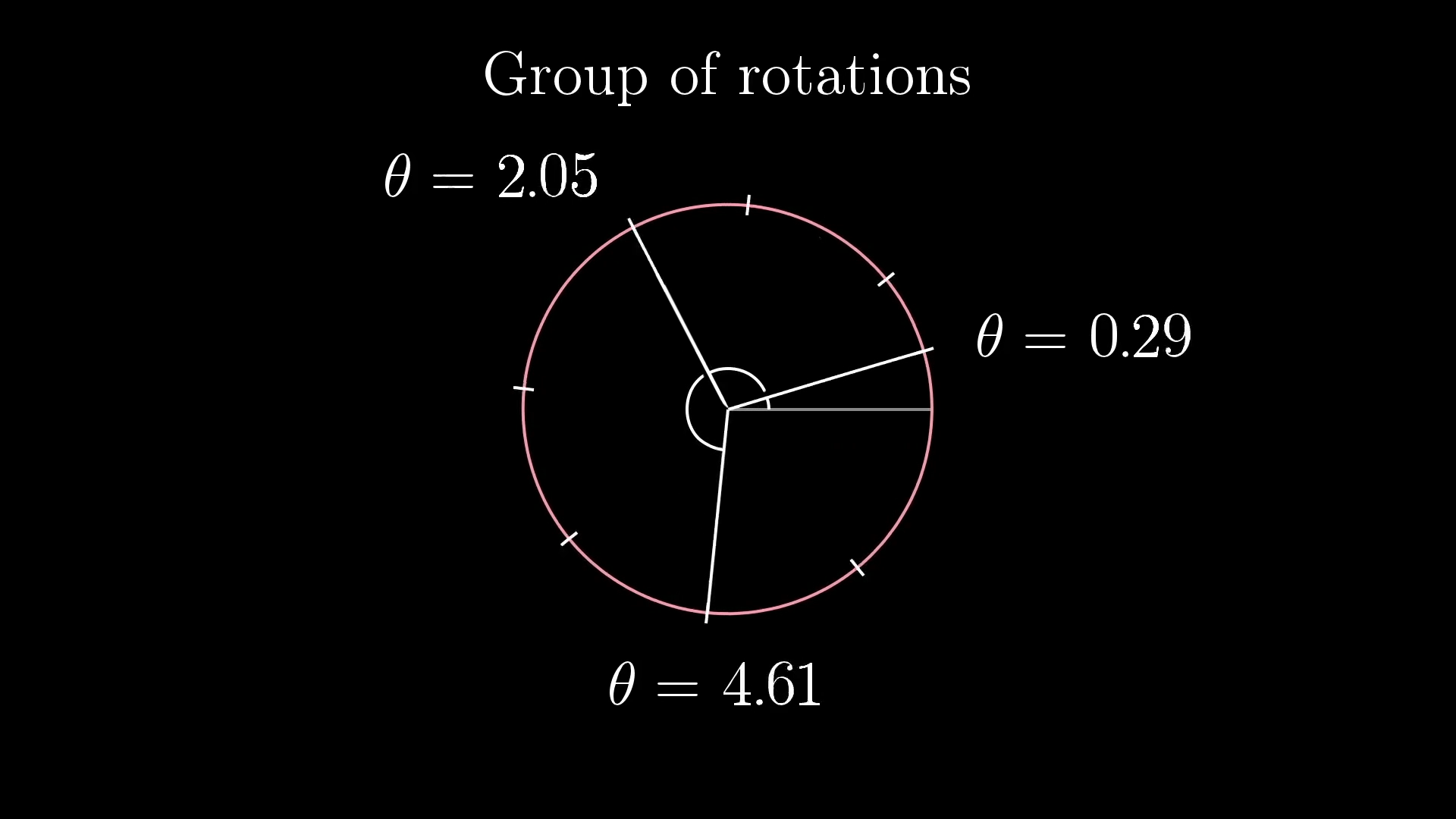

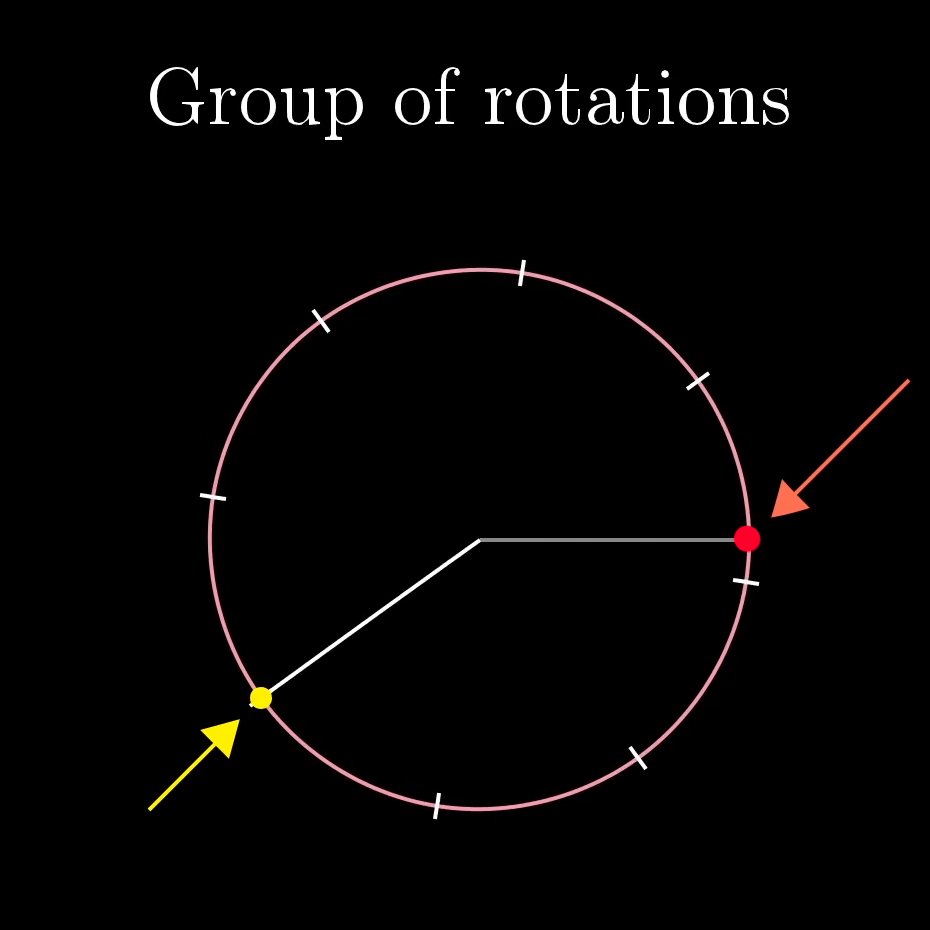

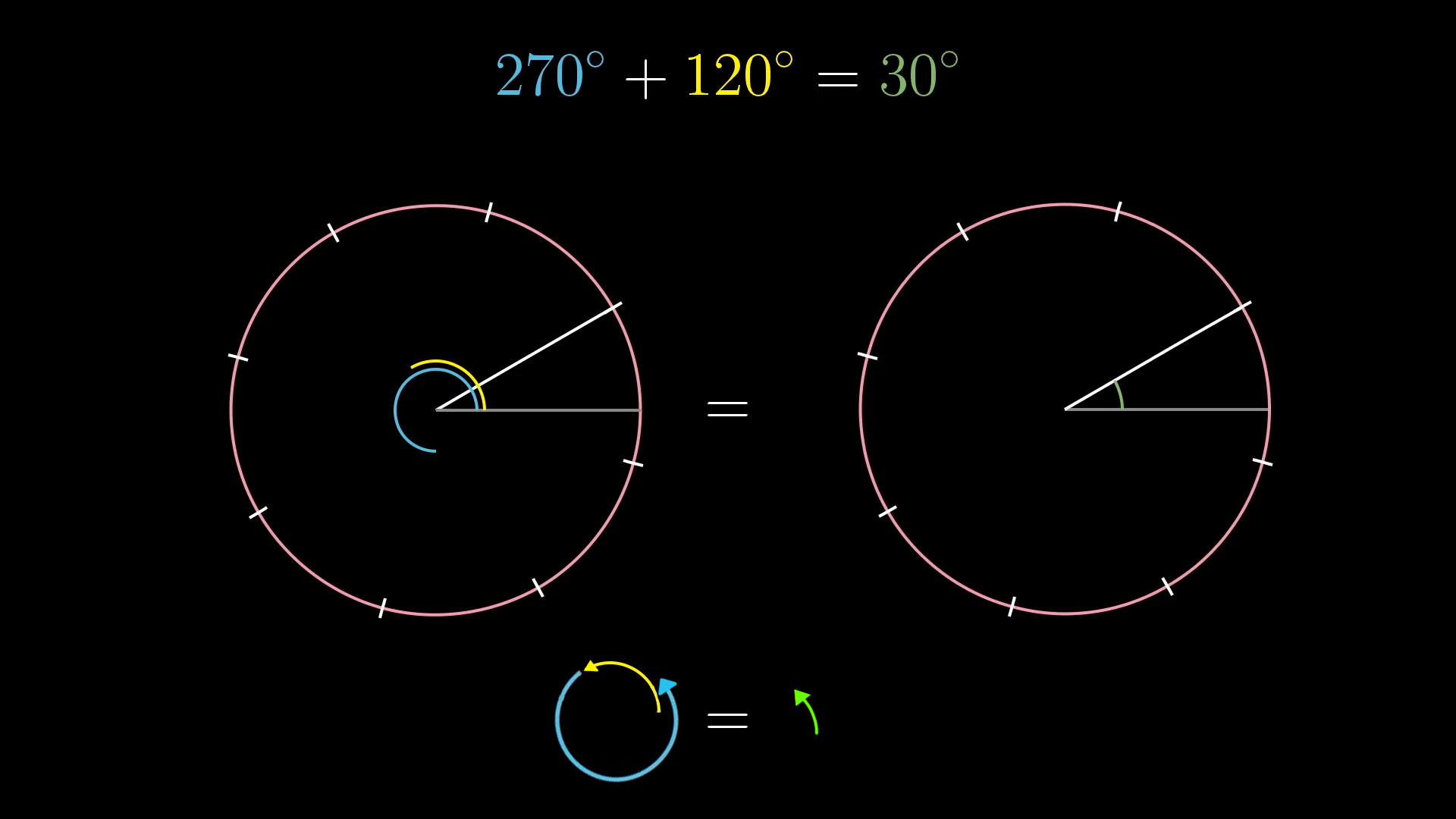

The square group is an example of a finite group, consisting of only 8 actions, but many other groups consist of infinitely many actions. Think of all possible rotations, of any angle; maybe you think of this group as acting on a circle, capturing all of the symmetries of that circle that don’t involve flipping it. Here, every action in the group of rotations lies somewhere on the infinite continuum between and radians.

One nice aspect of these actions is that we can associate each one with a single point on the circle itself, the thing being acted on. Start by choosing some arbitrary point, maybe this red spot. Then every circle symmetry, every possible rotation, takes this marked point to some unique spot, and the action itself is completely determined by where it takes that spot.

This doesn’t always happen with groups. Sometimes you can’t relate the group of actions with points on the thing they’re acting on. But it’s nice when it does happen, because it helps us actually label the actions themselves, which can otherwise be a bit hard to think about.

Composing Symmetries

The study of groups is not just about what a particular set of symmetries is; whether that’s the 8 symmetries of the square, the infinite continuum of symmetries of the circle, or anything else. The real heart of this study is in knowing how these symmetries play with each other.

On the square, if I rotate 90 degrees, then flip around the vertical axis, the overall effect is the same as if I had just flipped over this diagonal line. In some sense, that rotation plus the vertical reflection equals the diagonal reflection.

On the circle, if I rotate , then follow it with a rotation of , the overall effect is the same as if I had just rotated . So in this circle group, rotation plus a rotation equals a rotation.

In general, with any group, any collection of these sorts of symmetry actions, there’s a kind of arithmetic where you can always take two actions, and add them together to get a third by applying one after the other. Or maybe you think of it as multiplying actions, it doesn’t really matter, the point is that there’s some way to combine two actions to get another one.

What makes a group a group is all of the associations between pairs of actions, and the single action that’s equivalent to applying one after the other. It’s actually crazy how much of modern math is rooted in understanding how a collection of actions is organized by this relation between any pairs of actions, and the other action within the group you get by composing them.

If you rotate the square and then flip it around a vertical line, which action is that equivalent to?

Additive Group for Numbers

Groups are extremely general, a lot of ideas can be framed in terms of symmetries and composing symmetries. And maybe the most familiar example is numbers: just ordinary numbers.

There are actually two separate ways to think of numbers as a group, one where composing actions looks like addition, and one where it looks like multiplication. It’s a little weird, because we don’t usually think of numbers as actions, we usually think of them as counting things, but let me show you what I mean.

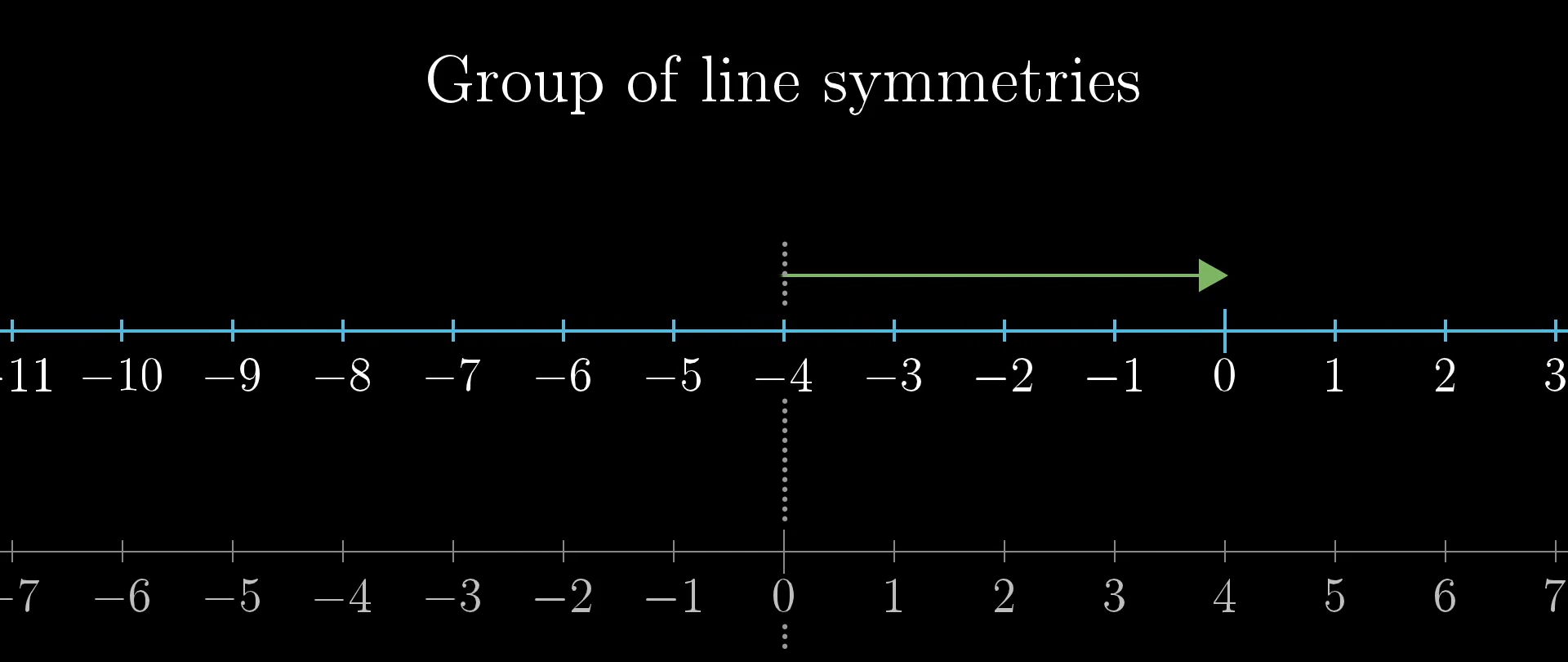

Think of all ways that you can slide a number line left or right along itself. This collection of all sliding actions is a group, what you might think of as a group of symmetries on an infinite line.

In the same way that actions from the circle group could be associated with individual points on the circle, this is another one of those special groups where we can associate each action with a unique point on the thing it’s acting on, you just follow where the point that starts at 0 ends up.

For example, the number 3 is associated with the action of sliding right by units. The number -2 is associated with the action of sliding units to the left, since that’s the unique action that drags the point at 0 over to the point at -2. The number 0 itself is associated with the action of simply doing nothing.

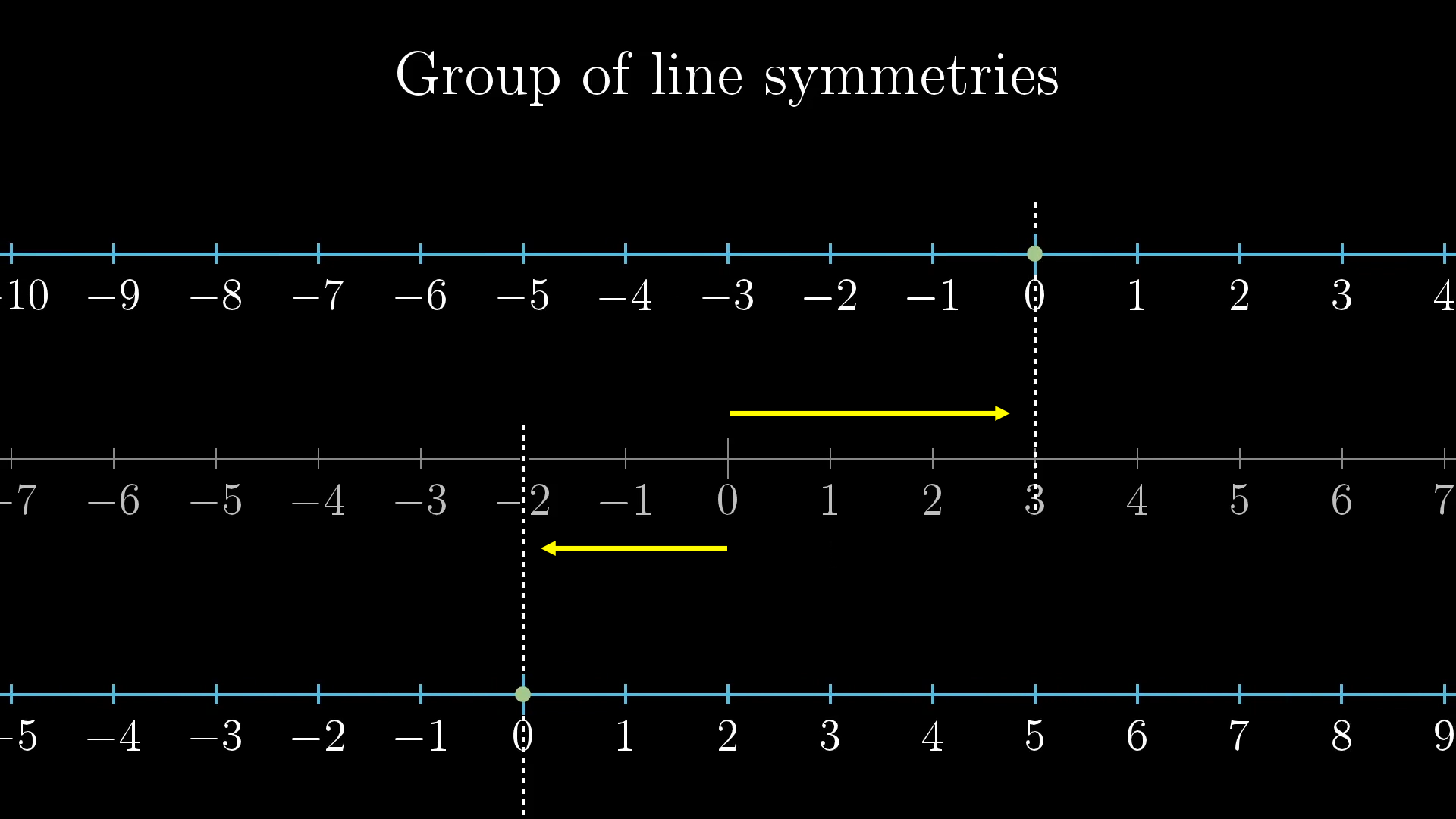

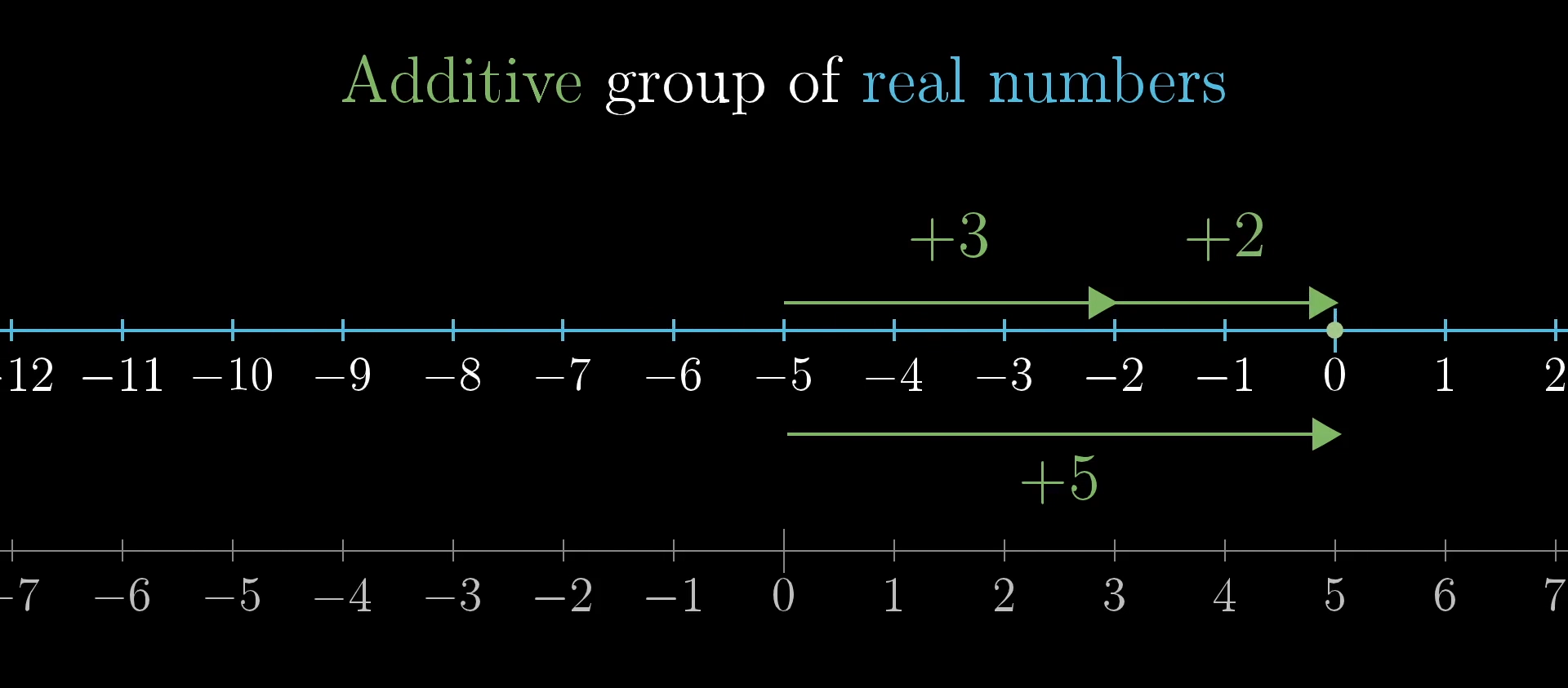

This group of sliding actions, each one of which is associated with a unique real number, has a special name: the “additive group of real numbers”. It’s called additive because of what the group operation of applying one action after the other looks like.

Simple enough, we’re adding the distances of each slide. The point here is that this gives an alternate view for what numbers even are. They are one example in a much larger category of groups; groups of symmetries on some object, and the arithmetic of adding numbers is just one example of the arithmetic that any group has within it.

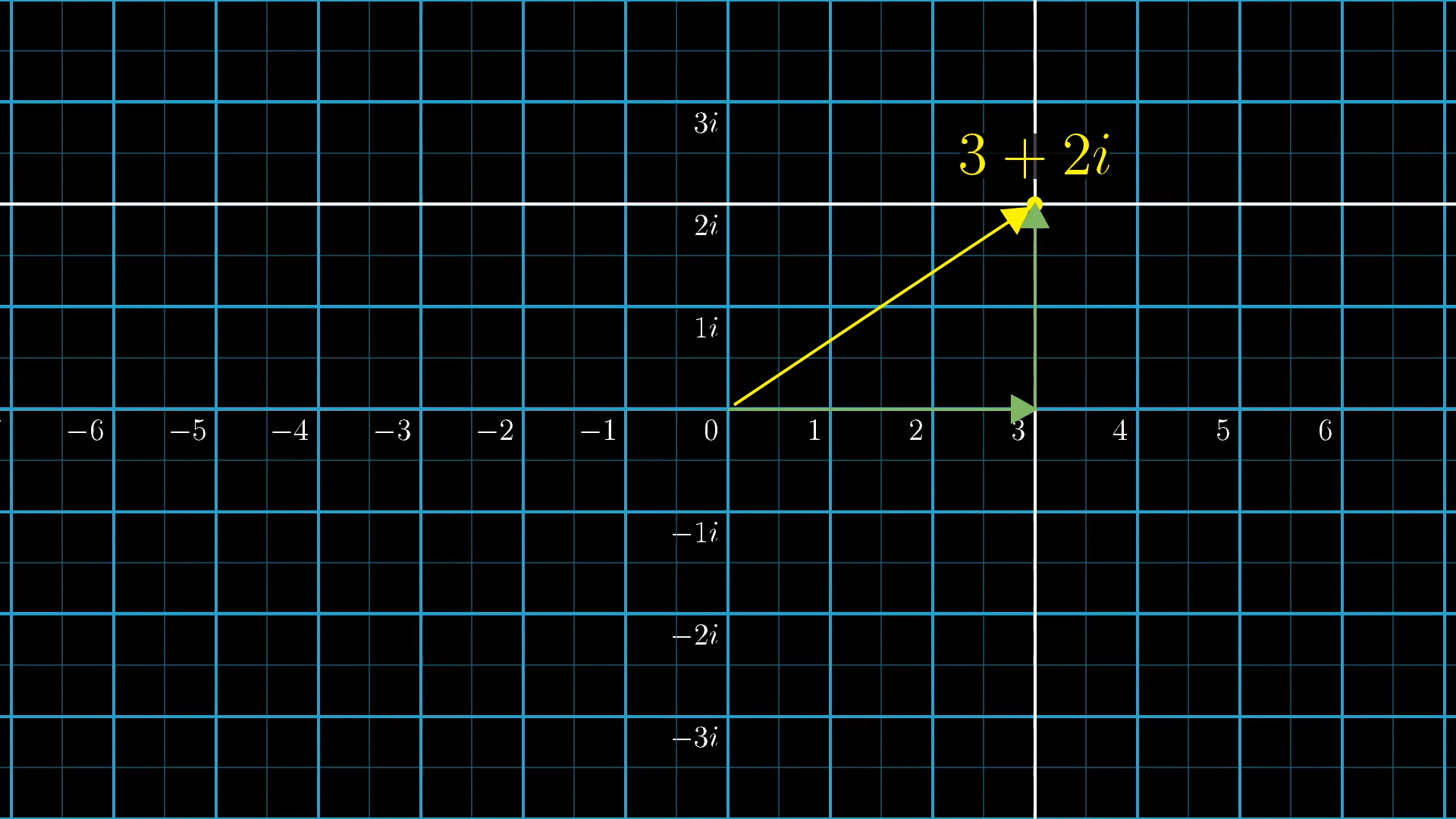

We can extend this idea, instead asking about sliding actions on the complex plane. The newly introduced numbers , , and the like on the vertical axis would be associated with vertical sliding motions, since those are the actions that drag the point at 0 up to the relevant point on that vertical line.

The point at would be associated with the action of sliding the plane in such a way that drags 0 up and to the right to that point. And it should make sense why we call this 3 plus : That diagonal sliding action is the same as first sliding by 3 to the right, then following it with a slide corresponding to , which is 2 units vertically.

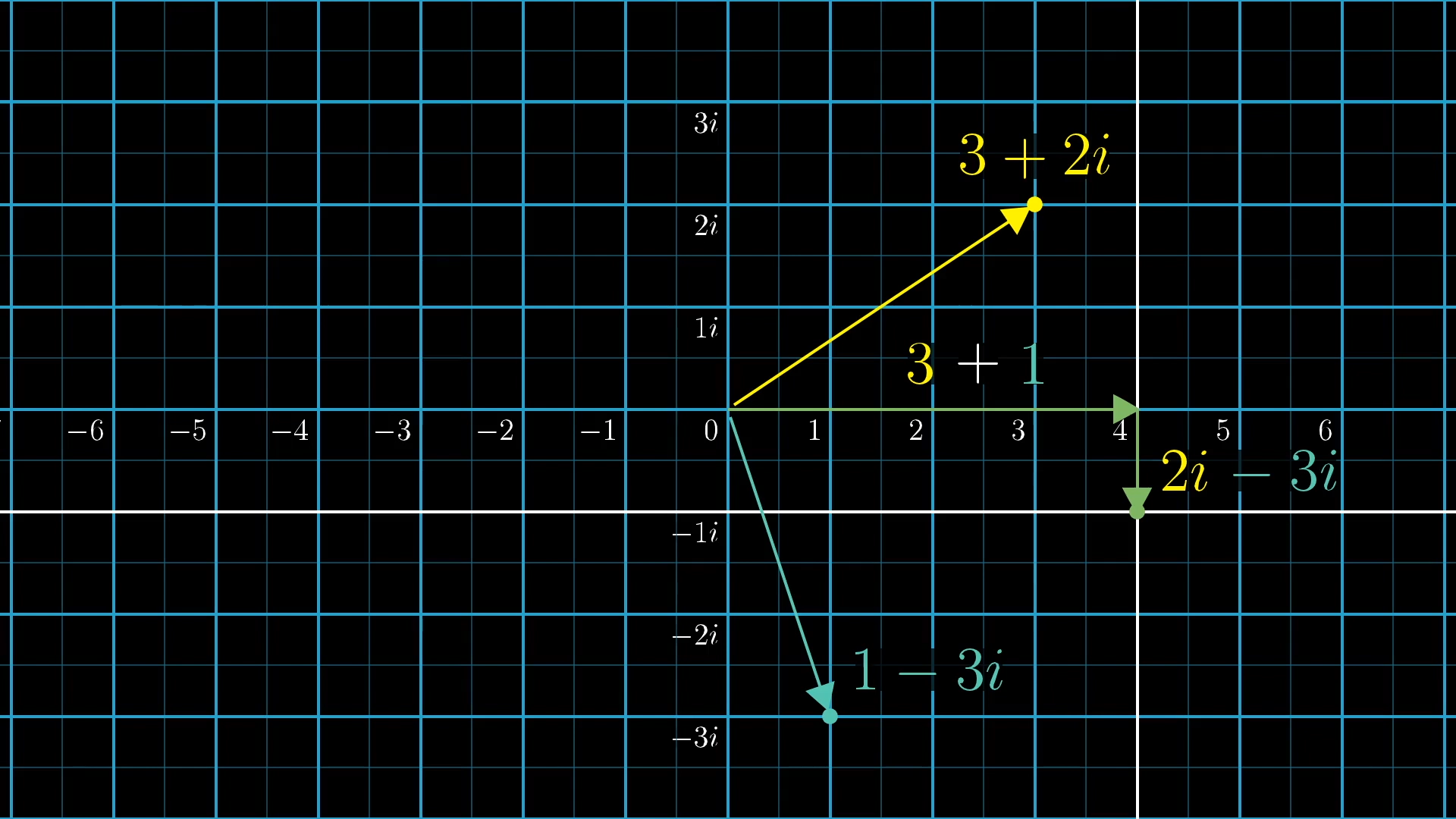

Similarly, look at how composing any two of these actions generally breaks down: Consider the slide by action, as well as the slide by action, and imagine applying one after the other. The overall effect, the composition of these two sliding actions, is the same as sliding to the right, and vertically. Notice how this involves adding together each component; so composing sliding actions is another way to think about what adding complex numbers means.

This collection of all sliding actions on the 2D plane goes by the name “the additive group of complex numbers.” Again, the upshot here is that numbers, even complex numbers, are just one example of a group, and the idea of addition can be thought of as successively applying actions.

Multiplicative Group for Numbers

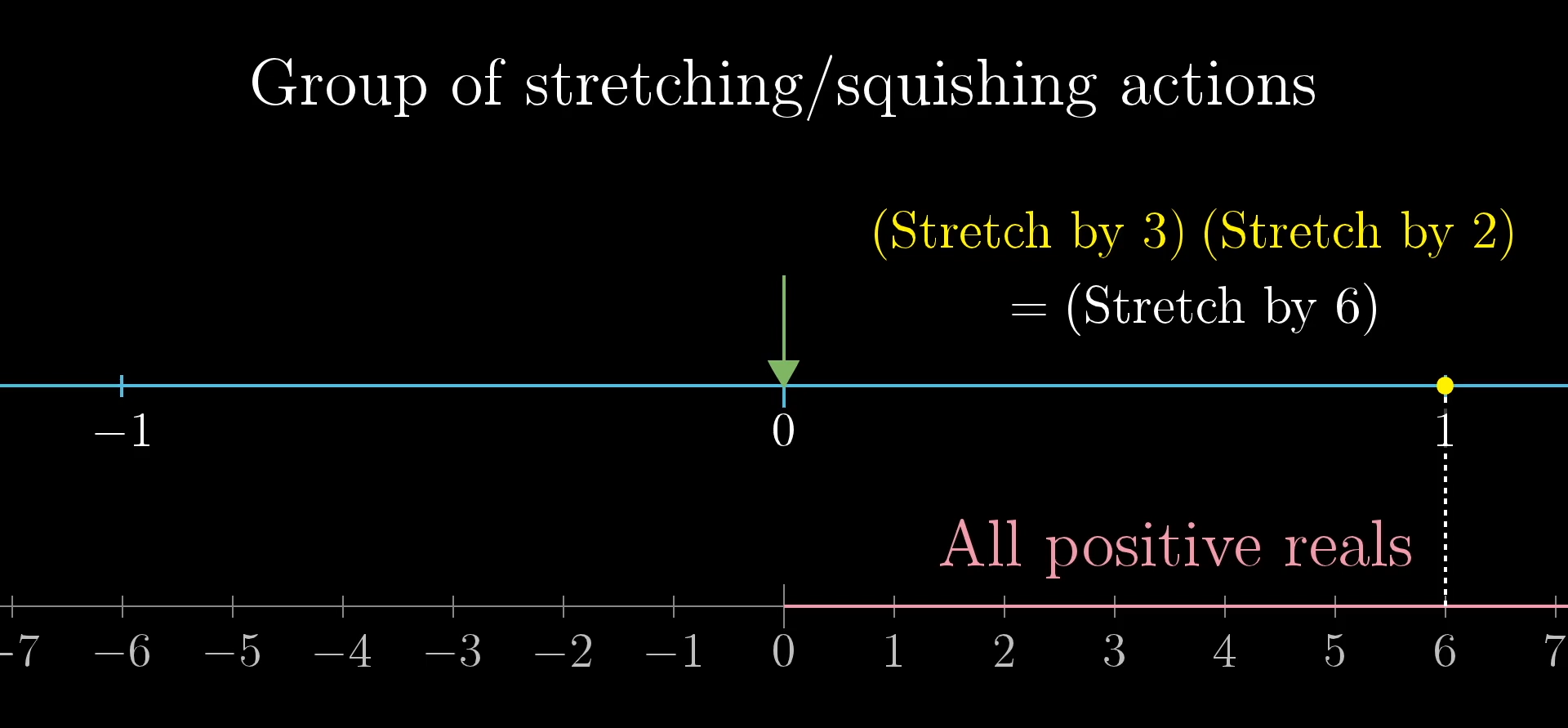

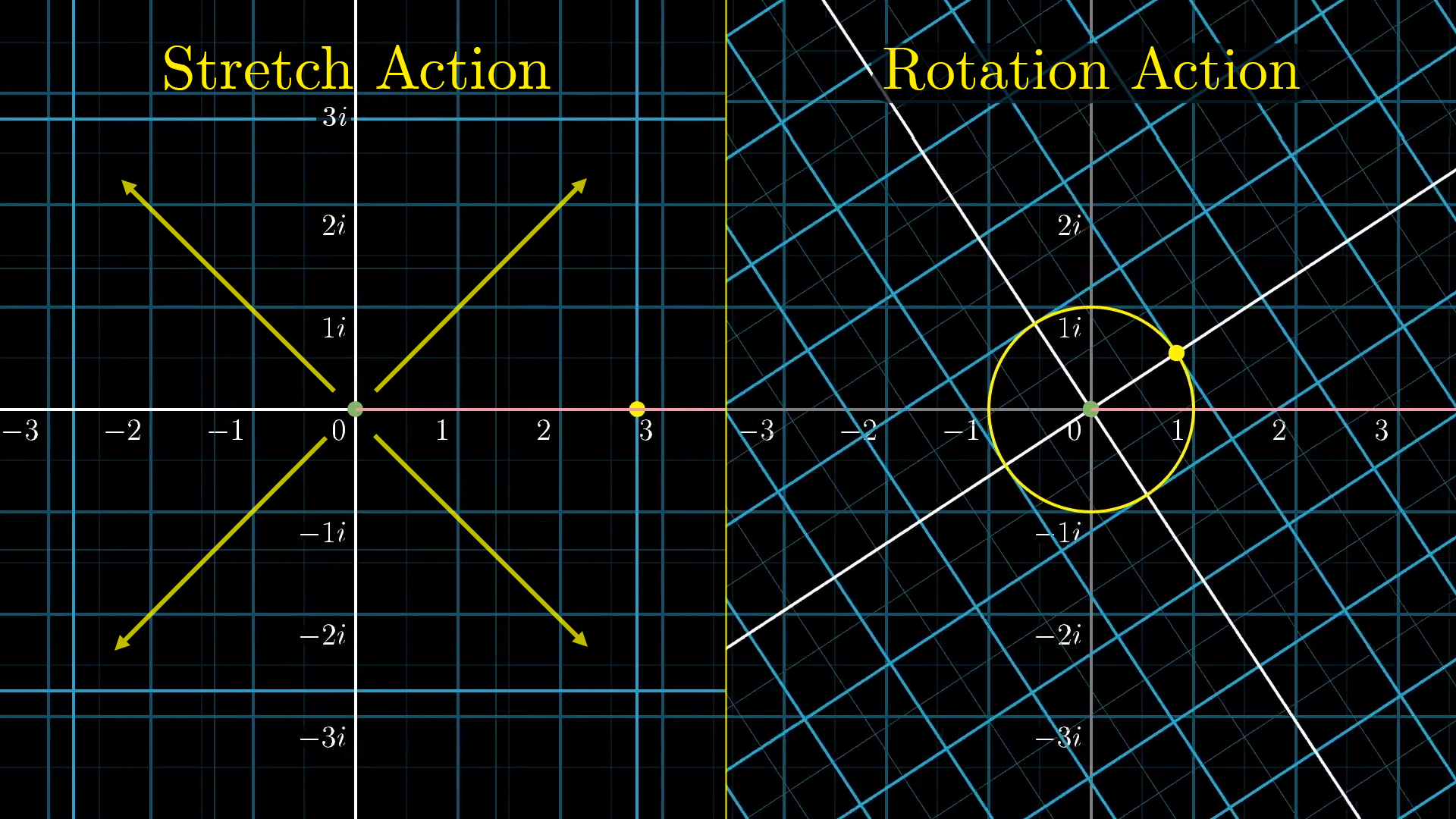

Numbers, multifaceted as they are, also lead a completely different life as a completely different kind of group. Consider a new group of actions on the number line: All ways of stretching or squishing it, keeping everything evenly spaced, and keeping 0 fixed in place.

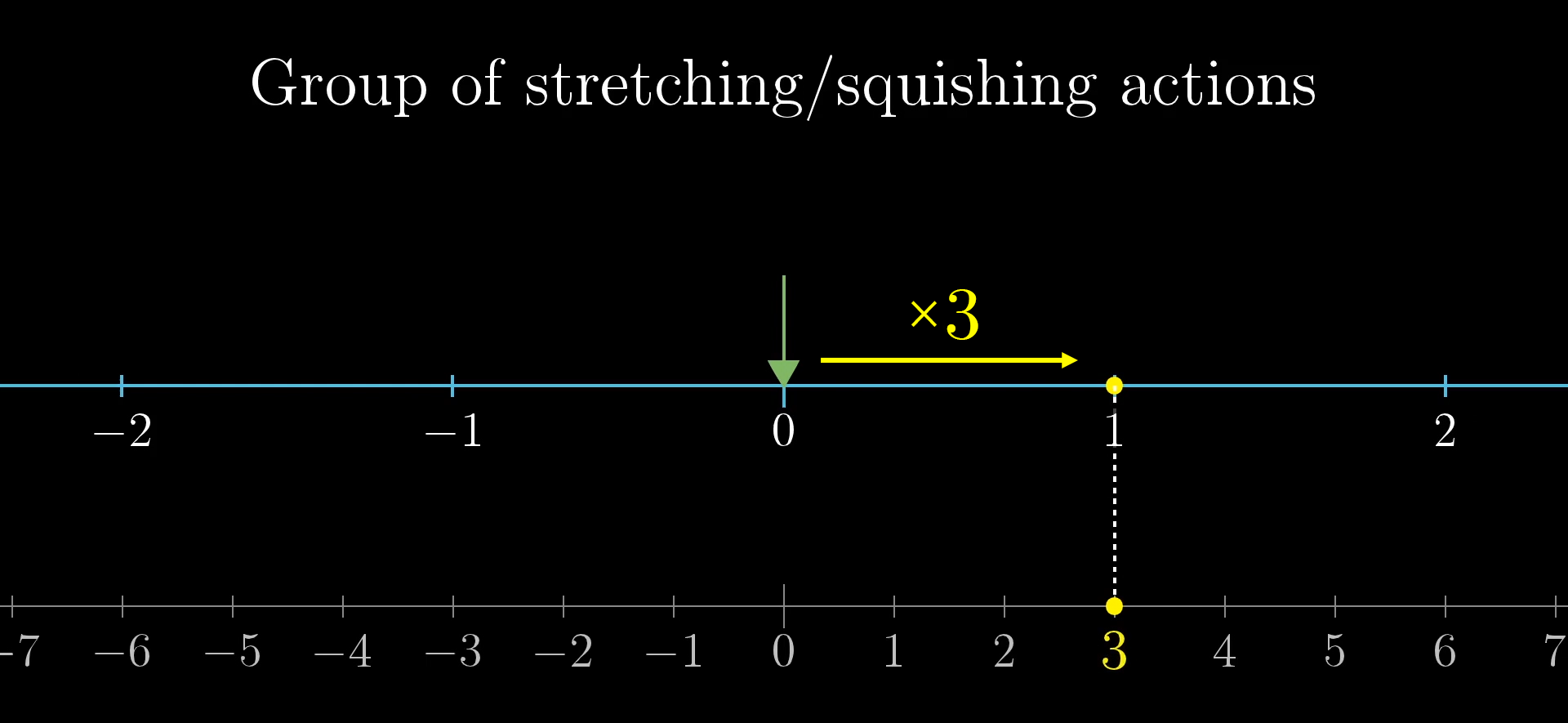

Yet again, this group of actions has that nice property where we can associate each action in the group with a specific point of the thing it’s acting on. In this case, follow where the point that starts at 1 goes. There is one and only one stretching action that brings that point at 1 to the point at 3, for instance. Namely, stretching by a factor of 3.

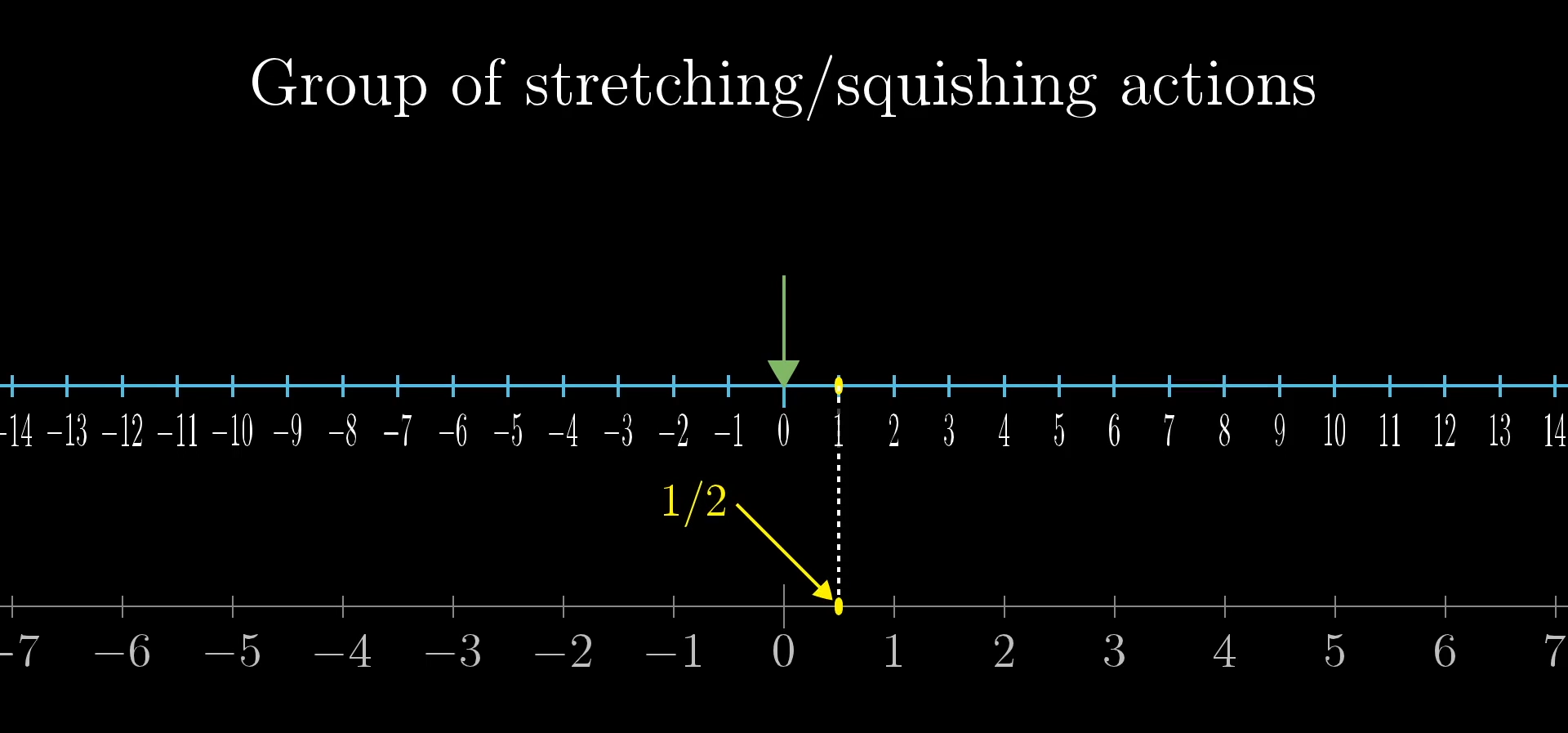

Likewise there is one and only one action that brings that point at 1 to the point at : Squishing by a factor of one half.

I like to imagine using one hand to fix 0 in place, as using the other to drag 1 wherever I like, while the rest of the number line does what it takes to stay evenly spaced. In this way, every positive number is associated with a unique stretching or squishing action.

Now notice what composing actions looks like in this group. If I apply the stretch by 3 action, and follow it by the stretch by 2 action, the overall effect is the same as applying a stretch by 6 action, the product of the two initial numbers.

Composing two stretches/squishes is the act of multiplying. Note that squishing the entire line to zero (i.e. multiplying by zero) is not part of the group because there is no inverse.

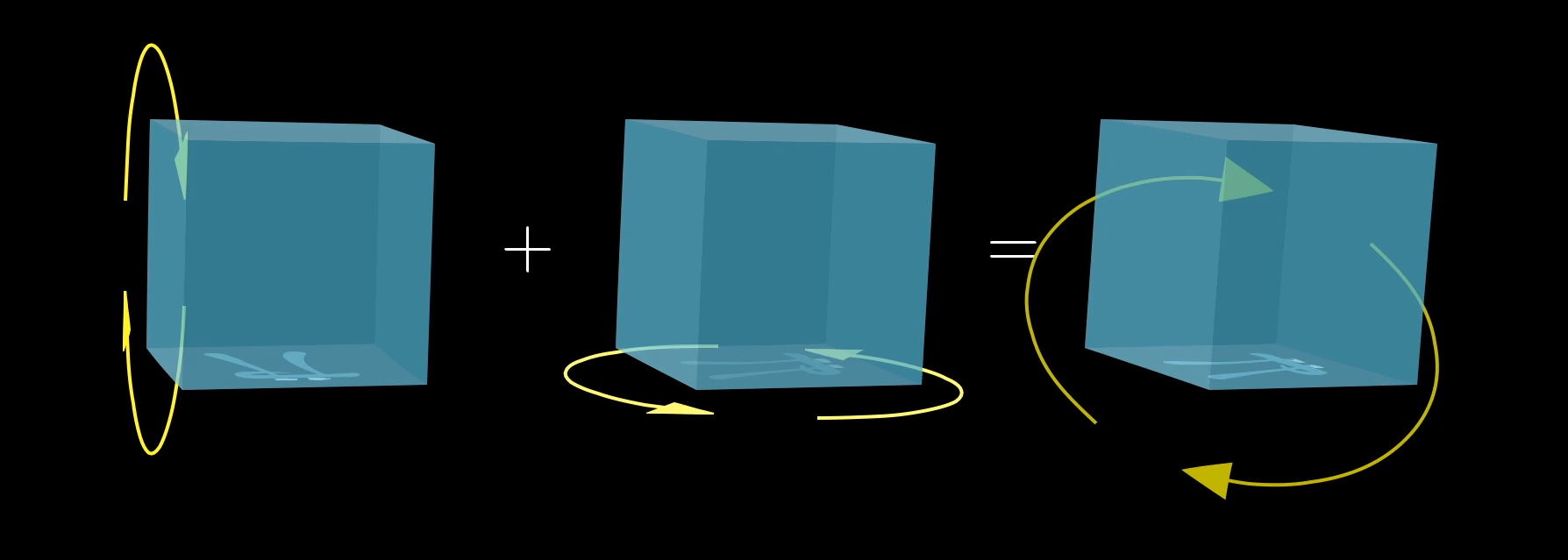

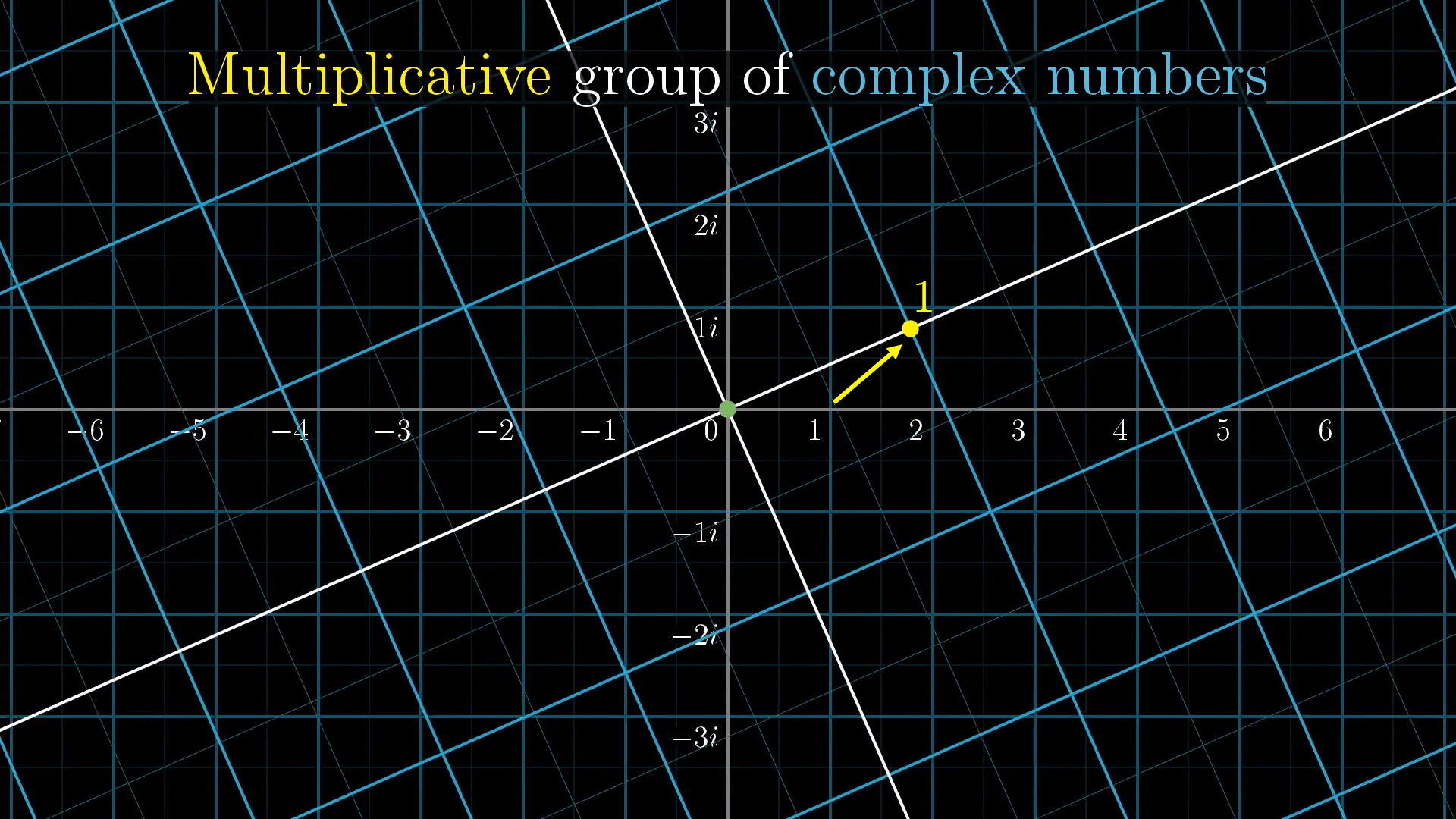

In general, applying one action followed by another here corresponds with multiplication. In fact, the name for this group is “the multiplicative group of positive real numbers.” So ordinary, familiar multiplication is one more example in this very general and far reaching idea of groups and the arithmetic within groups. We can also extend this idea to the complex plane. Again, I like to think of fixing 0 in place with one hand, while dragging around the point at 1, and keeping everything else evenly spaced while doing so.

But this time, as we drag the number 1 to places off the real number line, we see that our group includes not only stretching and squishing actions, but actions with some rotational component as well.

What group action could we take to move the point at to ?

Multiplying by the real number will squish the entire complex plane in a way which brings the point to .

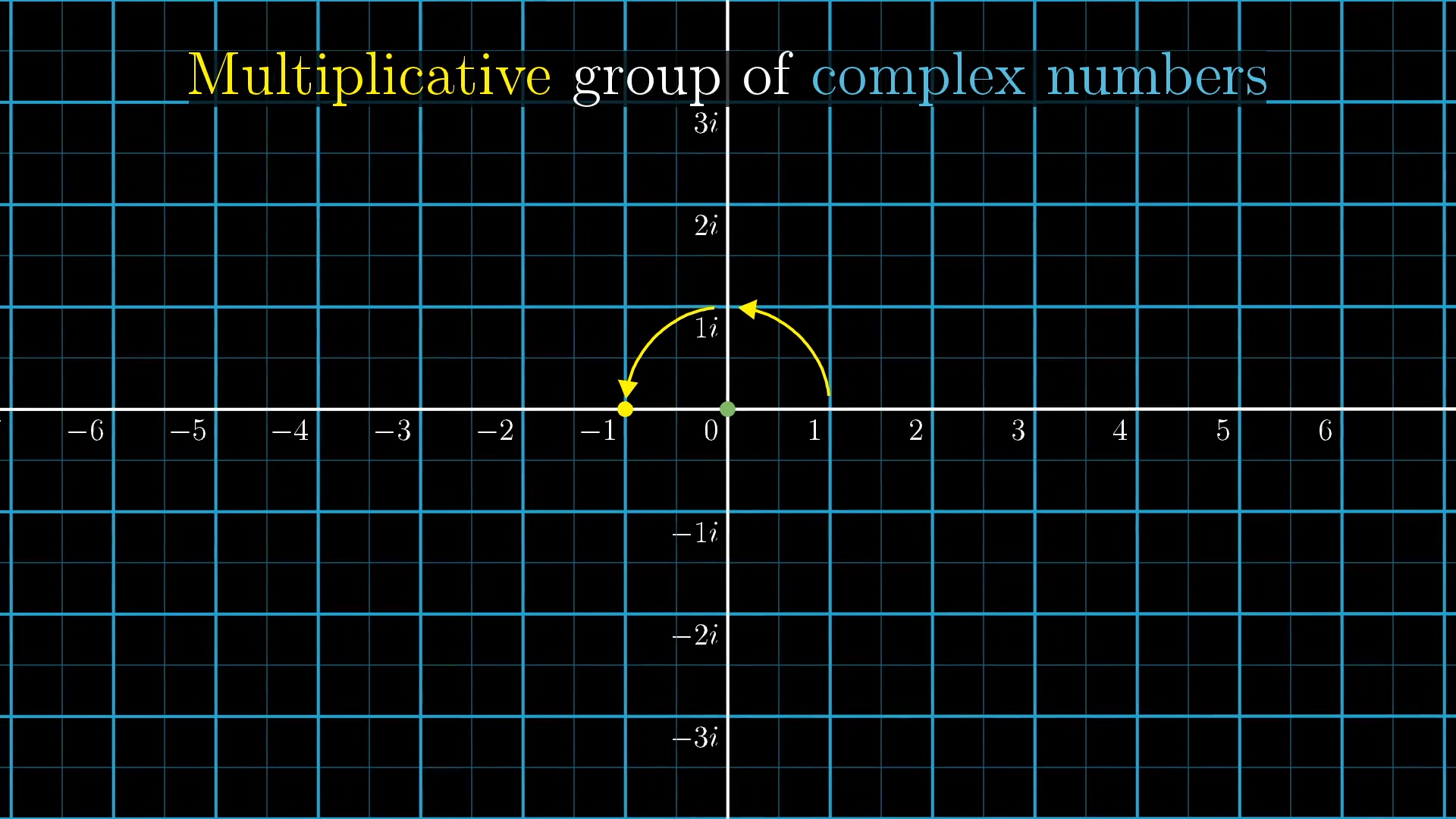

For example, think of the action associated with the point at , one unit above 0. What it takes to drag that point at 1 to the point at is a rotation. So the multiplicative action associated with is a rotation.

Notice, if you apply that action twice in a row, the overall effect is to flip the plane ; the unique action that brings the point at 1 over to -1.

In this sense, , meaning the action associated with , followed by that same action associated with , has the same effect as the action associated with .

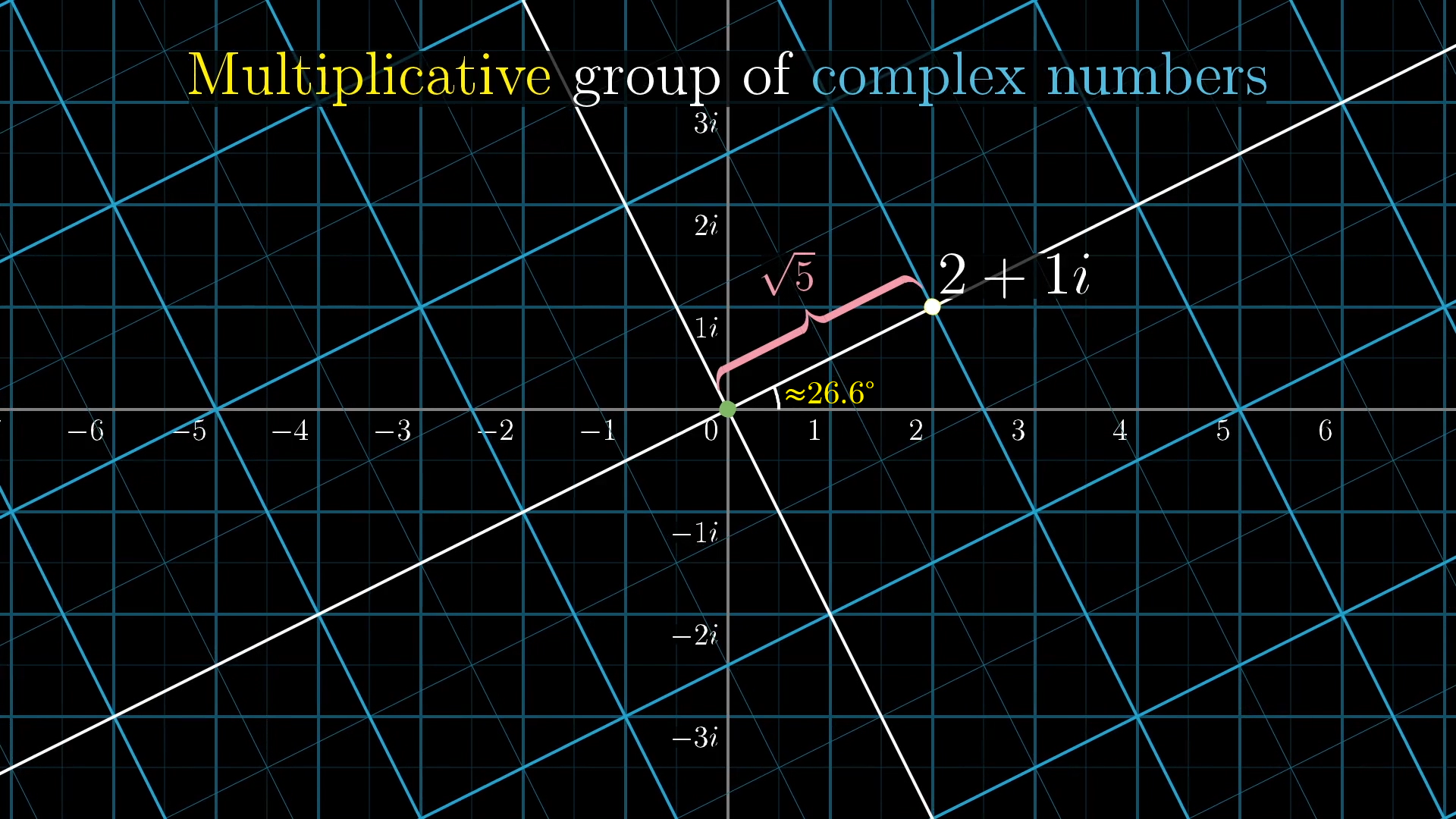

As another example, here’s the action associated with , dragging 1 up to that point. If you want, you could think of this broken down as a rotation by , followed by a stretch by a factor of .

In general, every one of these actions is some combination of a stretch or squish followed by a pure rotation. The stretch/squish action is associated with some point on the positive real number line. Whereas pure rotations are associated with points on the unit circle with radius .

This is similar to how any sliding action in the additive group of complex numbers could be broken down as some purely horizontal slide, represented with points on the real number line, plus some purely vertical slide, represented with points on the vertical line.

That comparison of how actions in each group break down is important, so remember it. In each, you can break down any action as some real number action, followed by something specific to complex numbers, whether that’s vertical slides for the additive group, or pure rotations for the multiplicative group.

What are Exponents?

So that’s the primer on groups. Groups are symmetric actions on some mathematical object, whether that’s a square, a circle, the real number line, or anything else you dream up. Every group has a certain arithmetic, where you can combine two actions by applying one after the other, and asking what other action from the group gives the same overall effect.

Numbers, both real and complex, can be thought of in two different ways as a group. They can act by sliding, in which case the group arithmetic looks just like ordinary addition. Or they can act by these stretching/squishing/rotating actions, in which case the group arithmetic looks just like multiplication.

Now let’s talk about exponentiation. Our first introduction to exponents is to think of them in terms of repeated multiplication, right? The meaning of something like is to take , and the meaning of is .

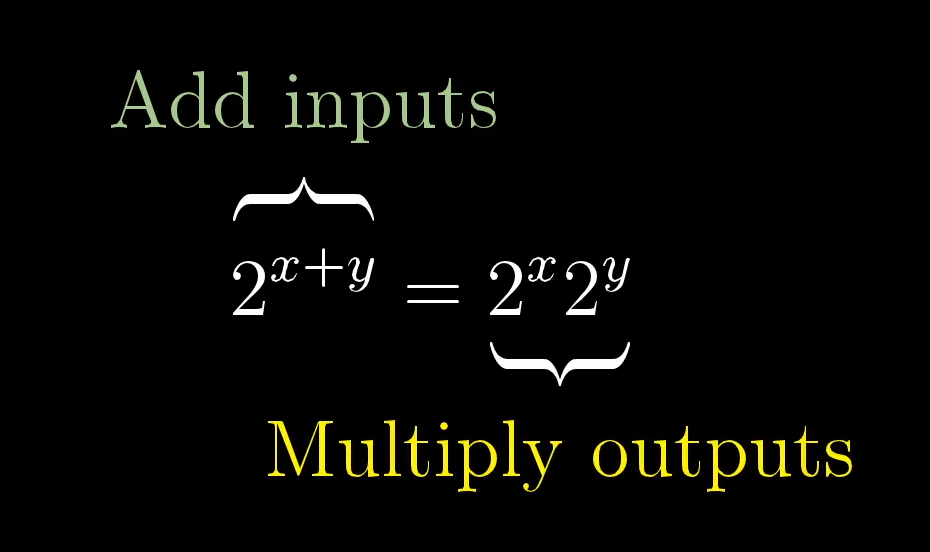

A consequence of this, something you might call the exponential property, is that if I add two numbers in the exponent, say this can be broken up into a product .

But expressions like or , and much less , don’t really make sense if you think of exponents as repeated multiplication. What does it mean to multiply 2 by itself half of a time, or of a time?

So we do something that’s very common throughout math, and extend the definition to apply to exponents beyond counting numbers. But we don’t just do this randomly, if you think back to how fractional and negative exponents are defined, it’s always motivated by trying to make sure this property = still holds.

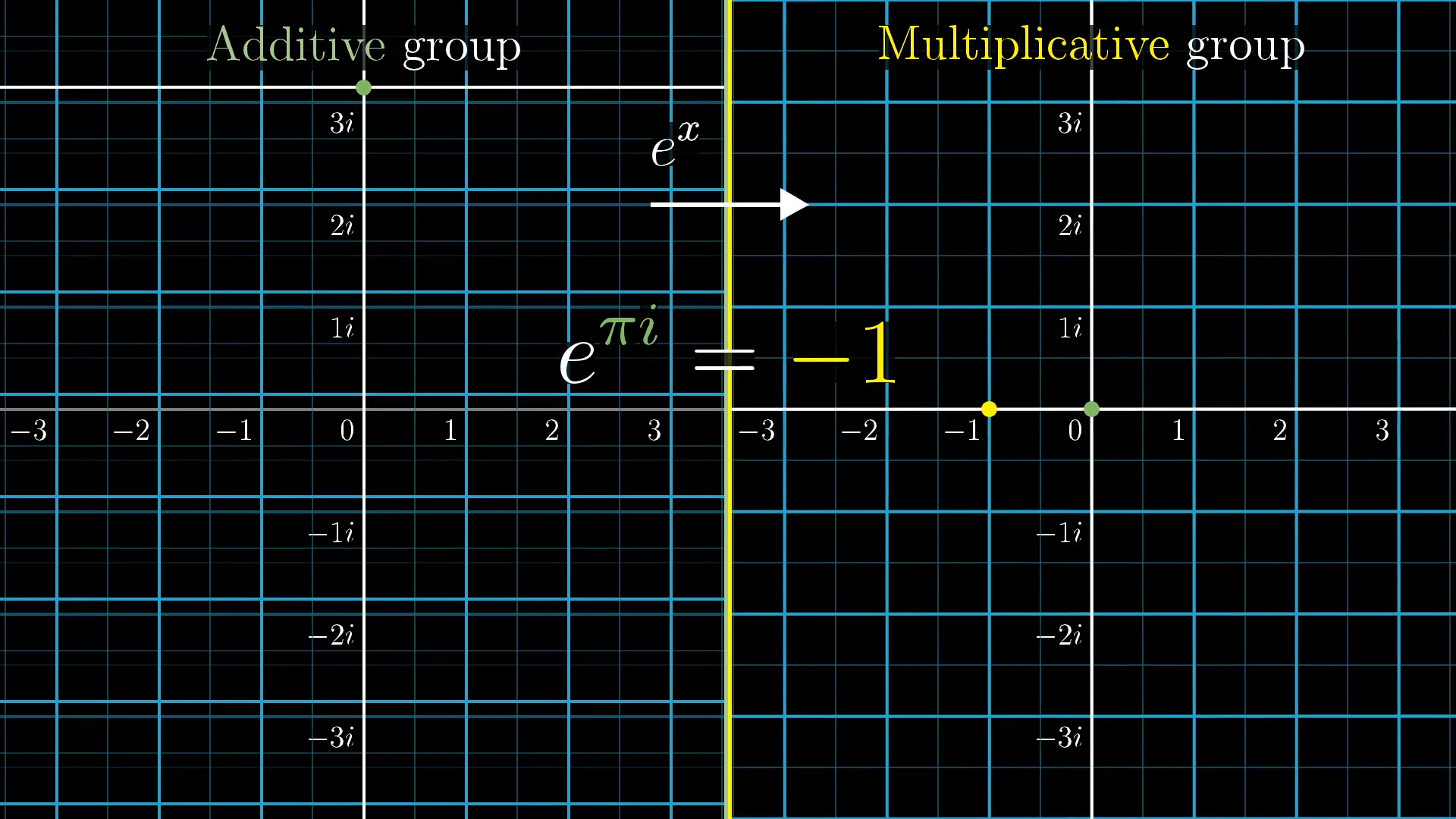

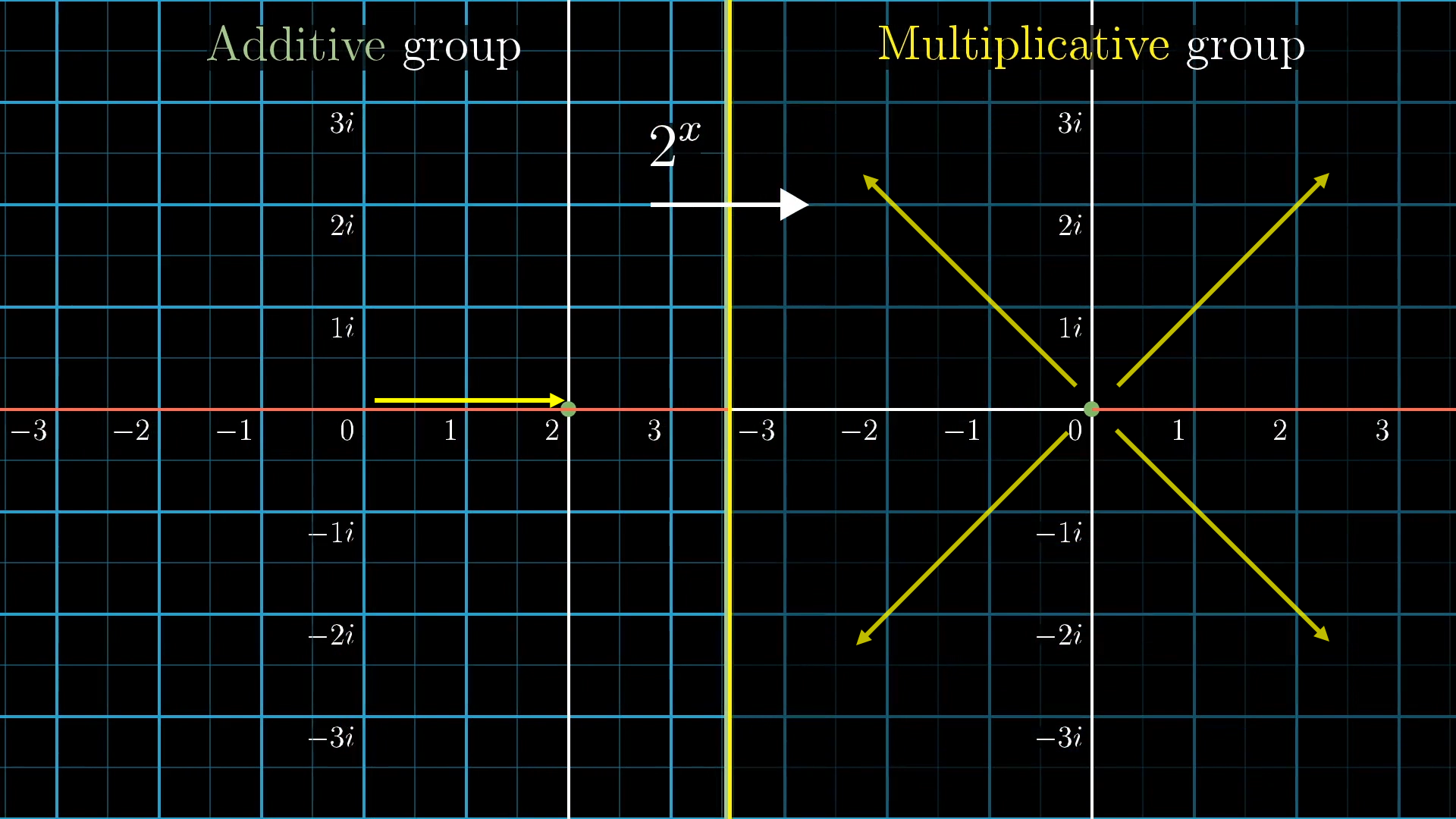

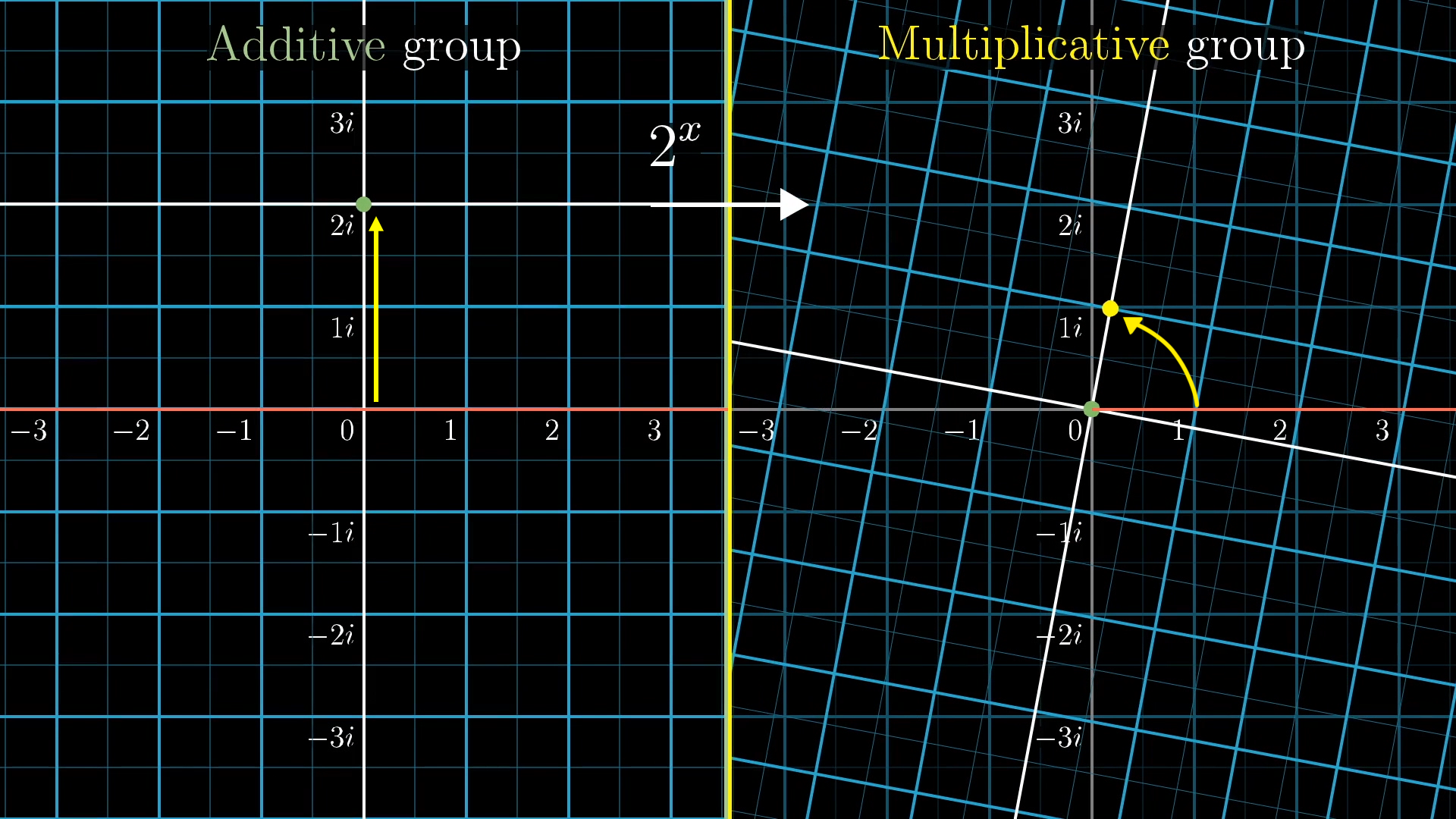

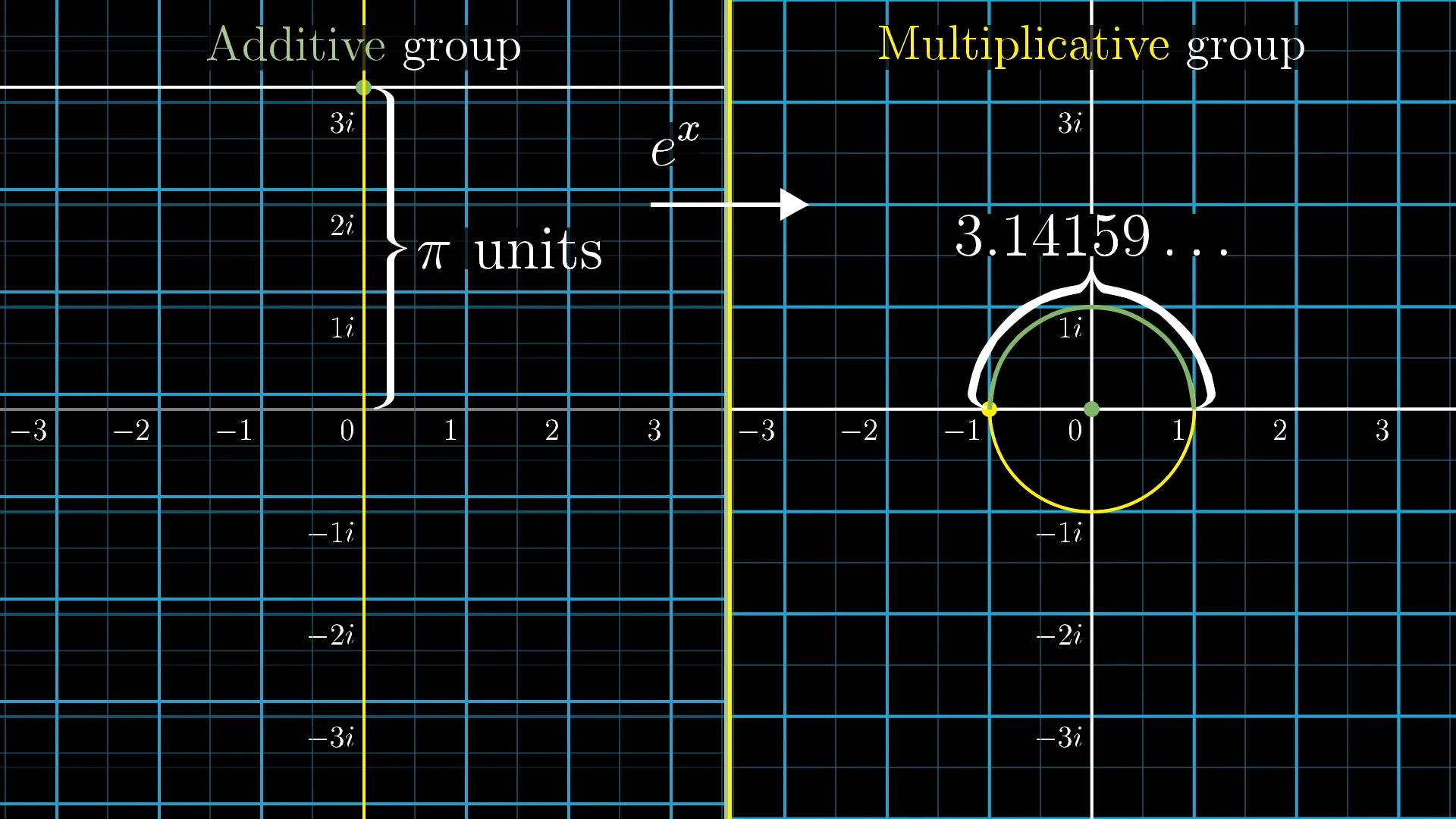

To see what this might mean for complex exponents, think of what this property is saying from a group theory perspective. It’s saying that adding the inputs corresponds with multiplying the outputs, and that makes it very tempting to think of the inputs not merely as numbers, but as members of the additive group of sliding actions, and to think of the outputs not merely as numbers, but as members of the multiplicative group of stretching and squishing actions.

It’s weird and strange to think about a function that takes in one kind of action and spits out another kind of action, but that’s actually something which comes up all the time in group theory. This exponential property is very important for this association between groups, it forms a map between the additive and multiplicative group for real numbers.

This exponentiation function guarantees that if I compose two sliding actions, maybe a slide by , then a slide by , it corresponds to composing the output actions, in this case squishing by , then stretching by .

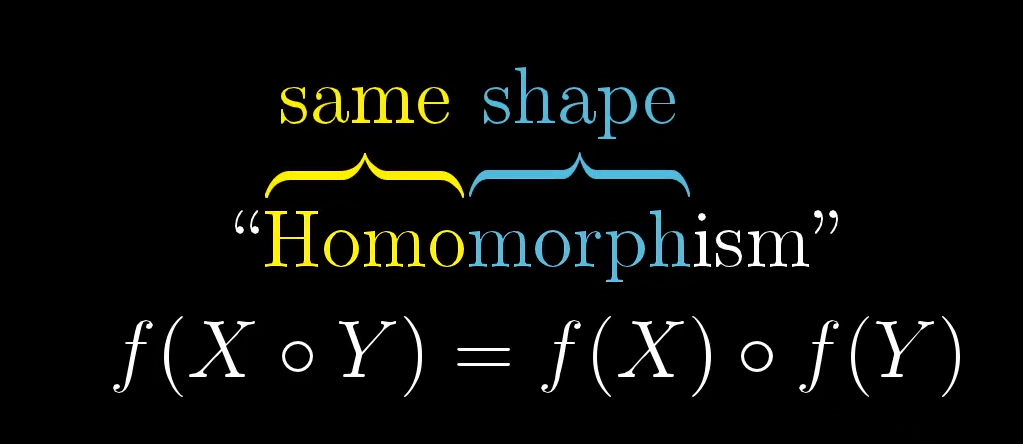

Mathematicians would describe a property like this by saying the function “preserves the group structure.” In this sense, the arithmetic within a group is what gives it its structure, and function like this exponential plays nicely with that arithmetic. Functions between groups that preserve the arithmetic like this are really important throughout group theory, enough so that they’ve earned themselves a fancy name: “homomorphisms.”

Complex Exponentiation

Now think about what this means for associating the additive group in the complex plane with the multiplicative group in the complex plane. We already know that when you plug in a real number to , you get out a real number, a positive real number in fact, so this exponential function takes any pure horizontal slide and turns it into some pure stretching or squishing action.

As we discussed above, there are two actions we identified with complex multiplication, a stretching action and a rotating action. Since the real component of a complex number already maps to the stretching action, it would be reasonable for this new dimension, the complex component that slides up and down, to map to the multiplicative action of rotation .

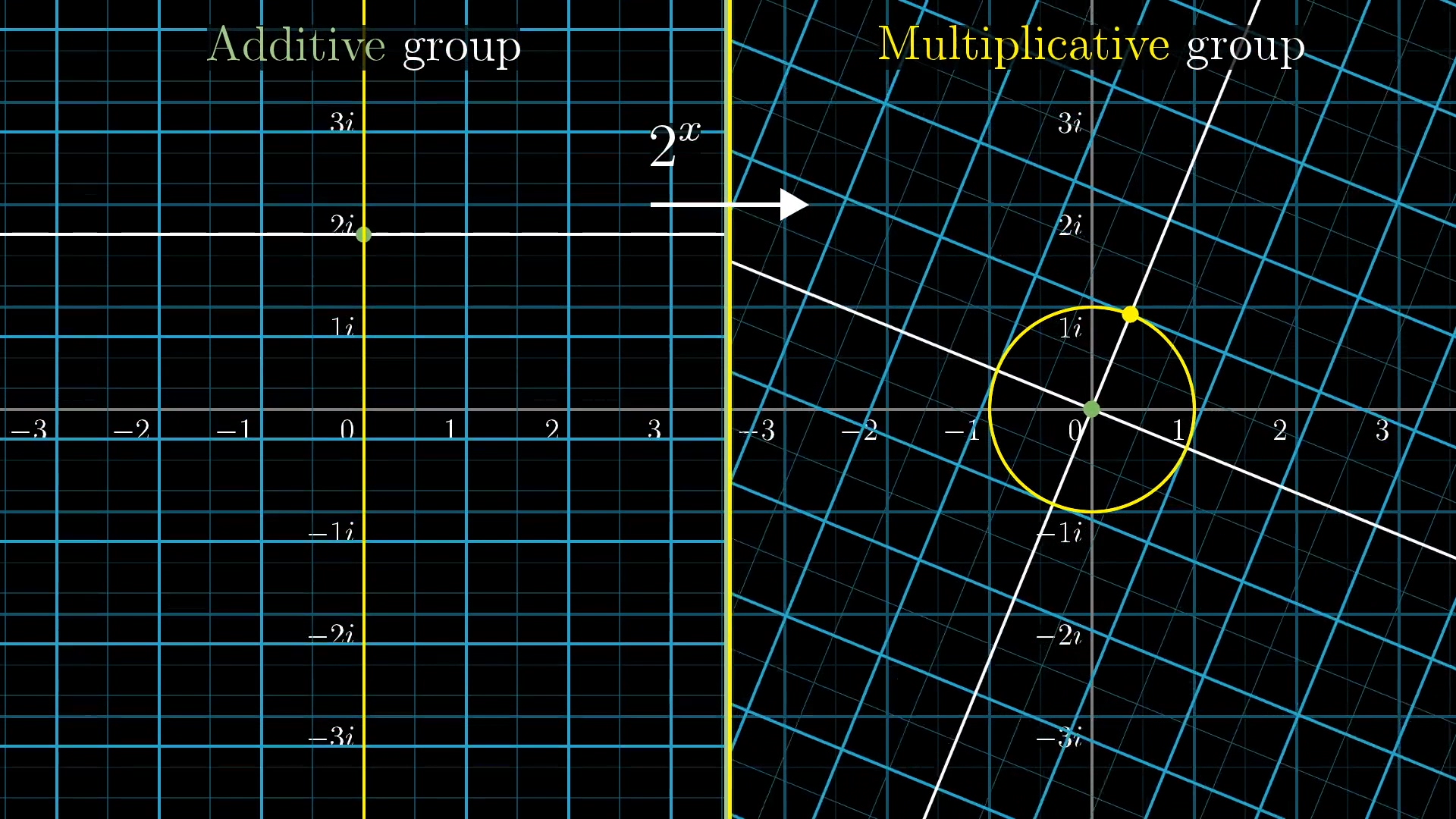

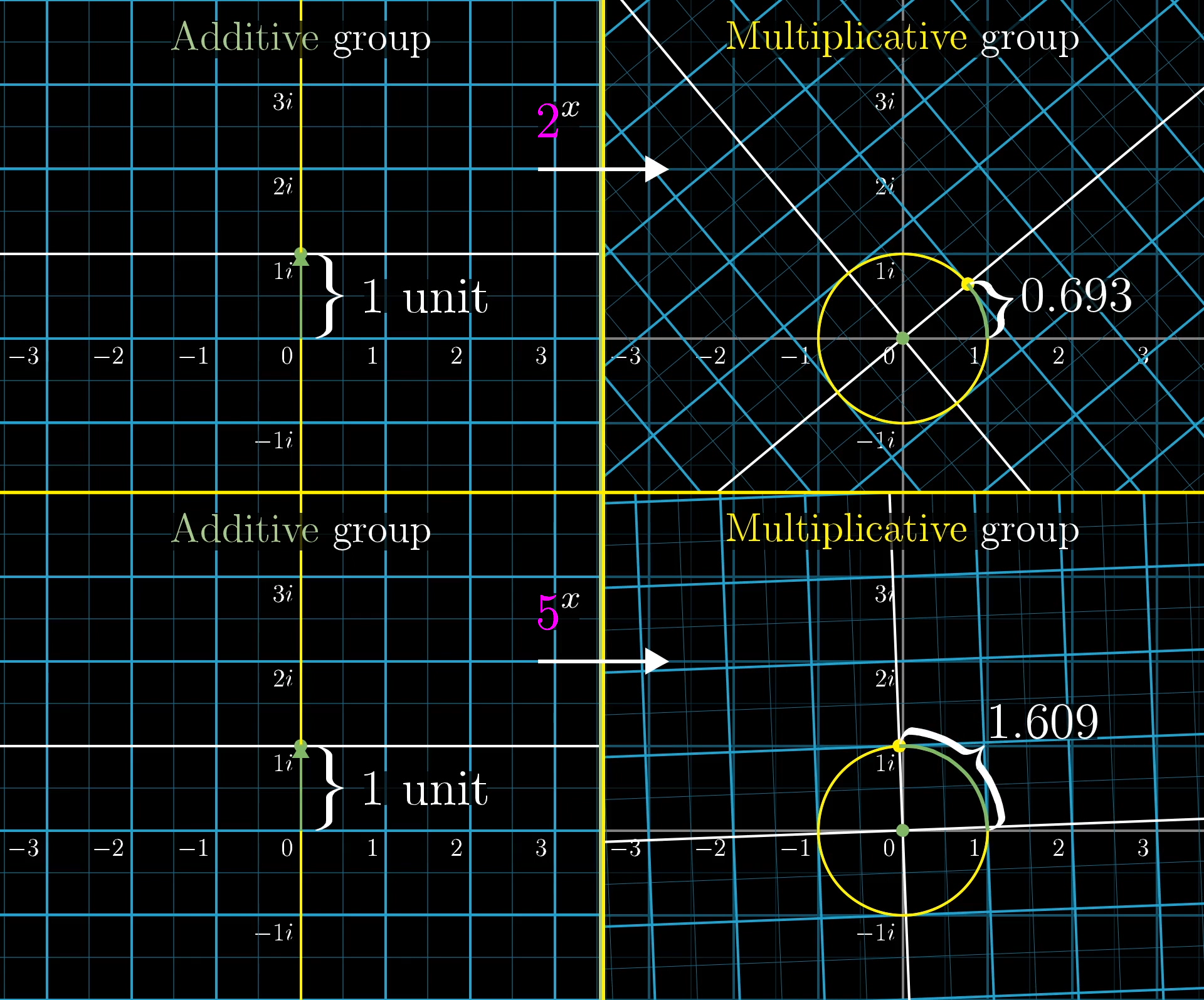

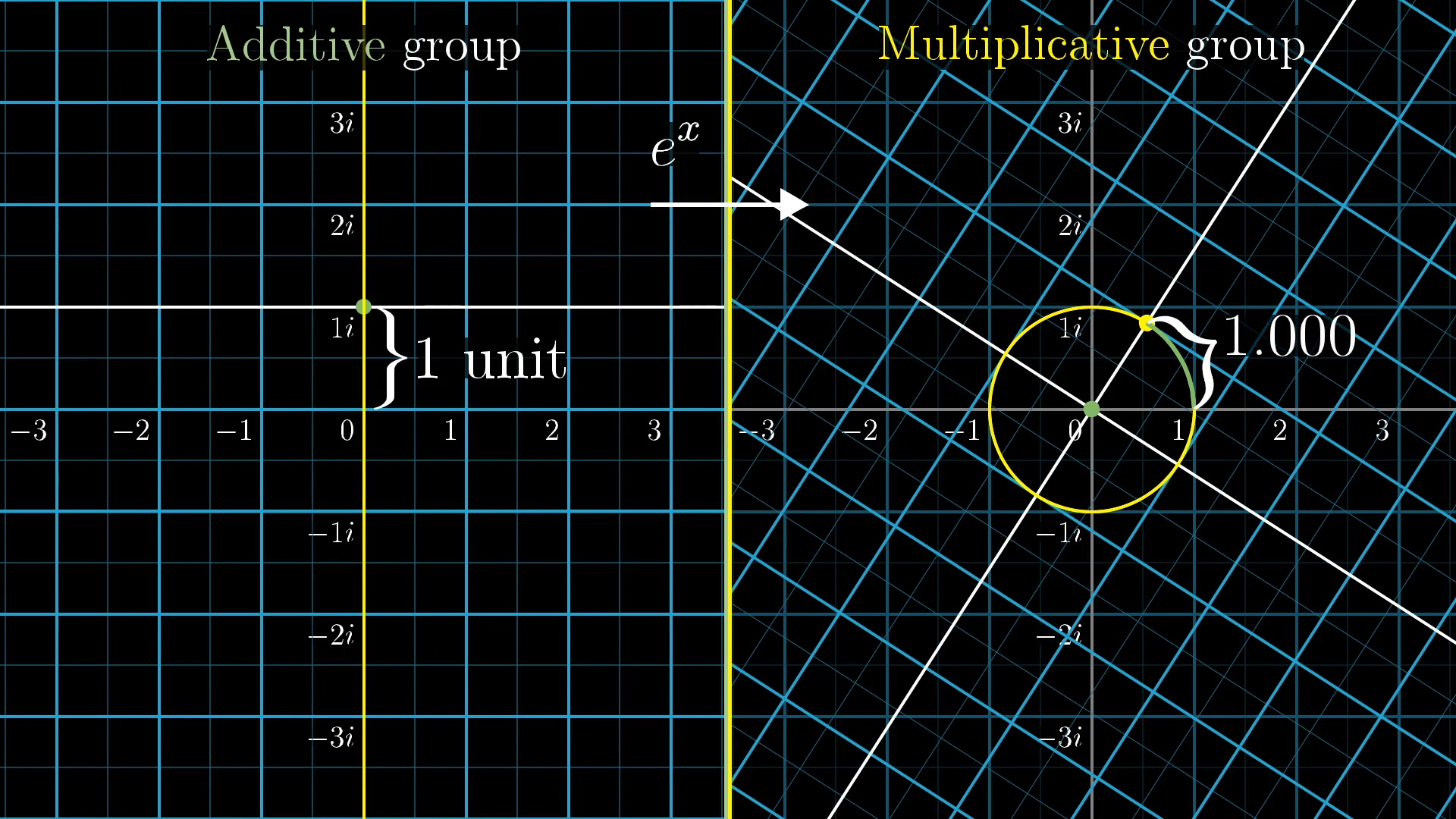

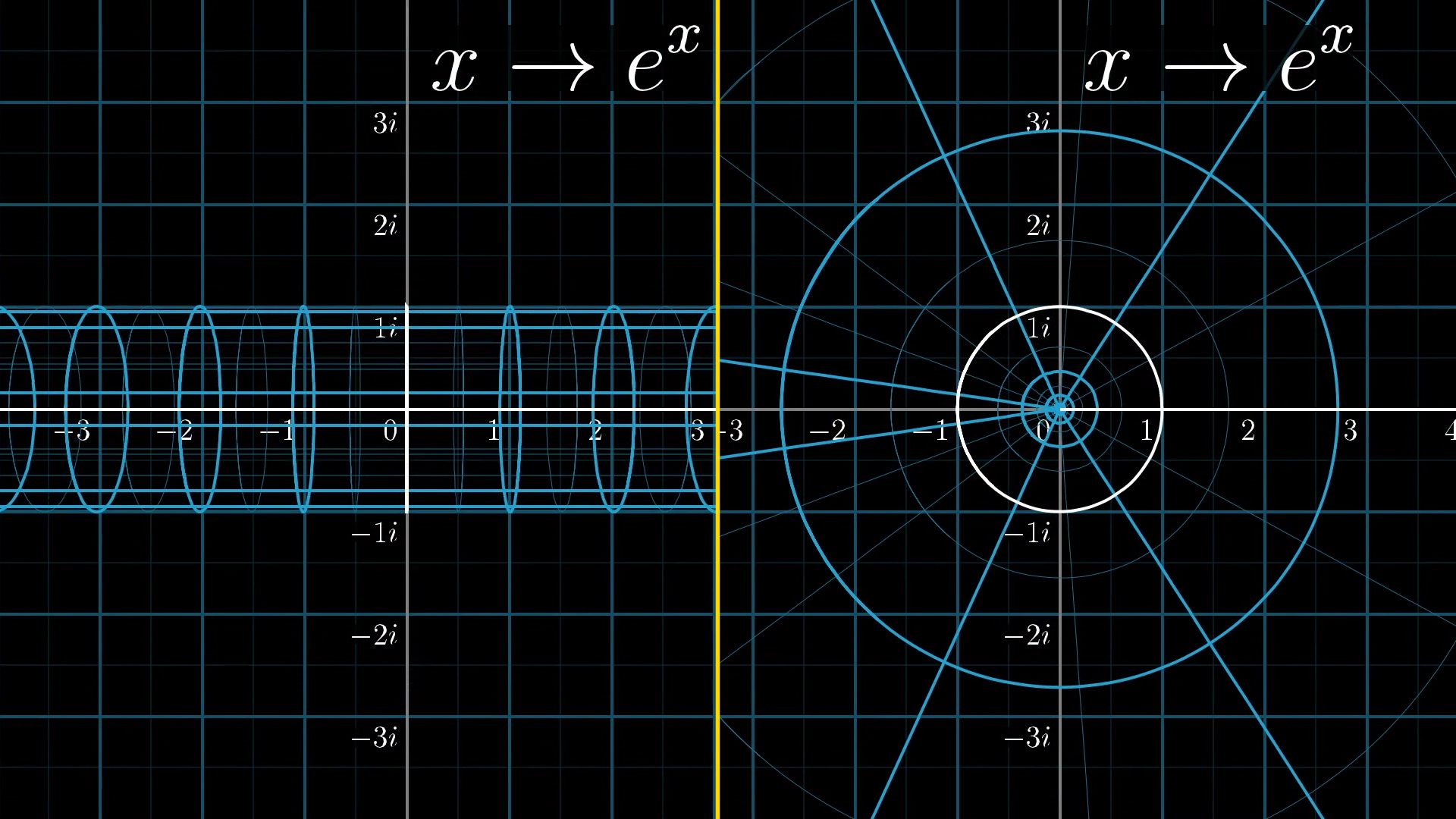

Each vertical sliding action corresponds to some point on the vertical axis of imaginary numbers. Using the exponentiation function, each point gets mapped to a point on the unit circle corresponding to a multiplicative rotating action.

In fact, for the function , the input , a vertical slide of 1 unit, happens to map to a rotation of radians. A walk around the unit circle covering units of distance. With a different exponential function, like , that input , a vertical slide of 1 unit, maps to a rotation of radians; a walk around the unit circle covering exactly units of distance.

What makes the number special is that when the exponential maps vertical slides to rotations, a vertical slide of one unit maps to a rotation of exactly 1 radian. Which is a walk around the unit circle covering a distance of 1.

And so, a vertical slide of units maps to to a rotation of radians, units up gives radians, and a vertical slide of units up, corresponding to the input , maps to a rotation of exactly radians, halfway around the circle, which is the multiplicative action associated to

Why ? Why not some other base? Well, the full answer resides in calculus; that’s the birthplace of , and where it’s defined. If you’re hungry for a fuller description, and comfortable with the calculus, this lesson dives into the specifics. At a high level, I’ll say it has to do with the fact that all exponential functions are proportional to their own derivative, but alone is actually equal to its own derivative.

We’ve seen that the imaginary axis turns into the unit circle under the transformation, but where does the rest of the complex plane end up? I like to imagine the plane first rolling up into a cylinder, wrapping all those vertical lines into circles. Then taking that cylinder, and smooshing it onto the plane around 0, where each of those concentric circles corresponds to what started as a vertical line.

The important point I want to make is that if you view things through the lens of group theory, thinking of the inputs to an exponential function as sliding actions, and thinking of the outputs as stretching and rotating actions, it gives a vivid way to read what a formula like this is even saying.

Exponentials in general map purely vertical slides, the additive actions that are perpendicular to real number slides, into pure rotations, which are in some sense perpendicular to real number actions. And moreover, does so in such a way that a vertical slide of units corresponds to a rotation of exactly radians; the 180 degree rotation associated with the number -1.

Thanks

Special thanks to those below for supporting the original video behind this post, and to current patrons for funding ongoing projects. If you find these lessons valuable, consider joining.